Symless: an IDA assistant for structure reconstruction

In 2023 we released Symless, an IDA Pro plugin designed to assist with structure reconstruction. Leveraging static code analysis, Symless automatically reconstructs structures, C++ classes and virtual function tables, while also handling cross-reference placement. At the time, it supported only x86 and x64 binaries, which was sufficient for our initial needs.

As it became part of our daily reverse-engineering workflow, its limitations quickly became apparent. This led us to develop a new, architecture-agnostic version. Today, we are excited to release this updated iteration and to take the opportunity to explain the ideas behind it.

This post first explores the core concepts and logic behind Symless, and then demonstrates the plugin’s capabilities through a practical use case.

Symless static analysis

Static data-flow analysis is used to gather information about a program’s structures. It involves tracking how data values are propagated and used throughout the code without executing the program. In this context, the data of interest are pointers to structures.

To illustrate, let’s consider the following assembly snippet:

mov eax, [rcx+10h]

add eax, [rcx+14h]

mov [rcx+18h], raxThe trained eye of a reverser will notice a structure being accessed three times through the rcx register. Assuming rcx points to the beginning of the structure, we can infer it has at least three fields and rebuild the following skeleton in IDA:

struct struc_1 { // sizeof=0x20

char gap0[0x10];

int32_t field_10;

int32_t field_14;

int64_t field_18;

};This deduction can be automated fairly easily. That is what Symless’s data-flow engine does: it propagates structure pointers through the code to identify accesses to structure fields. This information is later used to rebuild an accurate skeleton for each structure, and apply cross-references linking each field with its uses in the code.

Using the microcode

The former data-flow engine was designed for x64 instructions, thus limiting Symless to x64 (and x86) binaries. To overcome this limitation, the new version now uses IDA’s abstraction for disassembly: the microcode.

The microcode is IDA’s intermediate representation used in the process of translating machine-specific assembly code into the decompiled pseudocode. It takes the form of a reduced instruction set assembly language to abstract machine-specific details. For example, the previous x64 assembly snippets can be translated into the following microcode:

ldx ds, (rcx+10h), eax

add [ds:(rcx+14h)], eax, eax

xdu eax, rax

stx rax, ds, (rcx+18h)

Without describing each instruction, you can observe that this does not look very different from the original assembly code and can be used for data-flow analysis.

IDA can generate microcode for every architecture you have a decompiler for, meaning Symless now works on every program you can decompile. If you lack a decompiler license and only analyze x64 binaries, you can still use Symless’s previous version.

Finding entry points

Data-flow analysis requires an entry point, i.e. a starting instruction using a register holding a structure pointer to follow. To get as much information as possible, it is required to follow the evolution of the structure from its creation. Symless’s automatic analysis uses two kinds of entry points for this:

- dynamic memory allocations;

- C++ classes constructors.

Dynamic memory allocations are calls made to memory allocation functions. These functions are to be specified by the user in a .csv file. Each call is analyzed to reconstruct the potential structure it allocates. Heuristics are used to differentiate structure allocations from allocations of arrays or data buffers.

Heuristics are also used to identify the C++ virtual function tables used in a binary. Each table belongs to a C++ class and holds its associated virtual functions. From its virtual table, Symless can retrieve the class’s constructors and destructors. By propagating the “this” object in a class’s constructor, destructor and virtual functions, we are able to accurately rebuild the class.

Analyzing all the memory allocations and constructors present in a program allows to retrieve most of its structures. However this still misses some structures, the ones that are never dynamically allocated or C++ classes that do not use virtual functions and therefore do not own a virtual table.

Identifying duplicates

Using data-flow analysis, we can rebuild the structure associated with each entry point. The problem is that some of these anonymous structures may actually be the same. For example, if we have a foo structure being dynamically allocated three times in the program, we do not want to create three different structures foo_0, foo_1 and foo_2 (one per allocation).

To address this issue, a deduplication phase is implemented in Symless using heuristics to identify duplicated structures and merge them. The logic behind it is the following:

- First, identify related structures. Two structures are considered related if they are used in the same piece of code. For example, if during the data-flow phase we propagated two structures,

foo_0andfoo_1, as the first argument of abar()function, then we know they are related. - Next, within each group of related structures, determine which ones are identical (i.e. duplicated). This decision is based on heuristics matching the sizes and field layouts of the structures.

Two related structures are not always identical, one may be aggregated in the other or may inherit from the other (in case of C++ inheritance). It is sometimes difficult to state whether structures are duplicated or just sharing a common base. Because of this, Symless’s deduplication phase can be prone to errors: duplicates may be left behind or different structures may be wrongly merged.

Typing the code with structures

After creating all structures, each piece of code is typed with the structures it uses. Related structures raise another issue during this phase: when two structures were propagated in the same piece of code, how to decide which one to use for typing?

As an example, suppose we reconstructed three C++ classes foo, foobar and foobaz, with foobar and foobaz inheriting from their base class foo. The three were propagated as the first argument of a method foo::fct(), which belongs to the foo class. When typing this argument, Symless needs to decide which structure to use, here it should be foo and not foobar or foobaz.

void __fastcall foo::fct(foobar* this); // wrong

void __fastcall foo::fct(foobaz* this); // wrong

void __fastcall foo::fct(foo* this); // correctThis problem is about finding the common base shared by all conflicting structures. In our example both foobar and foobaz are built upon foo.

To find this common base, Symless searches for the least-derived structure: the simplest of the conflicting structures. When size-based heuristics are not enough to decide, we rely once again on heuristics that are not perfect. Because of this, the typing phase is also error-prone. Failures lead to functions being wrongly typed. An example of such failure follows in the use case.

It is important to note that no symbols or RTTI information is used by Symless in its heuristics (thus its name). This allows it to work just as well on fully stripped binaries. Symbols are only used to rename the created structures and fields.

Symless on a use case

Now that we have explained how it works, let’s see how to run Symless on an example. We will analyze a library from Qt’s macOS installation: QtCore. This C++ library, compiled to a universal Mach-O file containing two architectures (x64 and arm64), proved very convenient for testing across different architectures. For this example, we consider the arm64 variant and show how to run Symless’s pre-analysis and interactive plugin on it.

Pre-analysis mode

Symless’s first operating mode, described above, is an automatic analysis retrieving entry points from the binary and using data-flow analysis to rebuild structures. This mode is intended as a pre-analysis step prior to manual reversing. It reconstructs structures and types the code with them, improving the quality of the decompiled code.

Because we want Symless to rebuild dynamically allocated structures, we have to fill in the allocators used by QtCore in the imports.csv file:

1/usr/lib/libSystem.B.dylib, _malloc, malloc

2/usr/lib/libc++.1.dylib, __Znwm, malloc # operator new(unsigned long)

Here we describe two imported functions: malloc from the libSystem and the operator new from the libc++. Symless will identify any wrappers around these allocators and analyze all allocations made with them. We decide not to add other allocators like calloc or realloc, as they are mostly used for allocating arrays or data-buffers.

Once the allocators are filled in, we can run the pre-analysis by using the symless.py script:

bob:symless$ python3 ./symless.py ~/QtCore.i64

Using IDA installation: "/home/bob/idapro-9.1"

Running IDA script..

* IDAT : /home/bob/idapro-9.1/idat64

* Script: /home/bob/symless/symless.py ("--config", "/home/bob/symless/symless/config/imports.csv", "--prefix", "qtlrry")

* Base : /home/bob/QtCore.i64

* Logs : /tmp/QtCore_i4fogrt3.log

This script takes one argument: a binary or IDA database to analyze. When given a binary, a new database will be created. Your IDA installation folder should be automatically located. If not, you need to add the idat executable to your PATH or set the IDA_DIR environment variable to point your IDA folder.

The analysis on this 12 MB library takes a few minutes. A log file is created and filled with potential errors as the analysis runs. When finished, reopen the database in IDA to find the reconstructed structures in the local types view, under a “Symless” folder. On this example Symless is able to recreate 583 structures and classes and 204 virtual function tables.

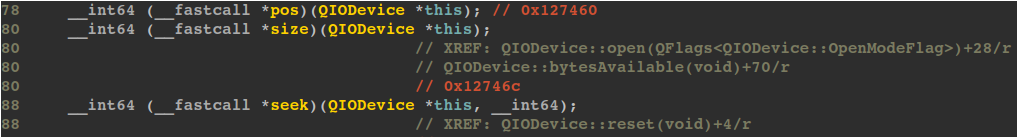

This analysis automatically improves the decompiled pseudocode of functions using the recreated structures. To illustrate this, we will focus on the open() method of the QIODevice class. IDA’s vanilla pseudocode for this function is shown below:

QIODevice::open without Symless’s pre-analysis.

Two structures are manipulated here:

a1 (the QIODevice object) and

v2 (a QIODevicePrivate object). We also see an indirect call at line 11 to one of QIODevice’s virtual methods.

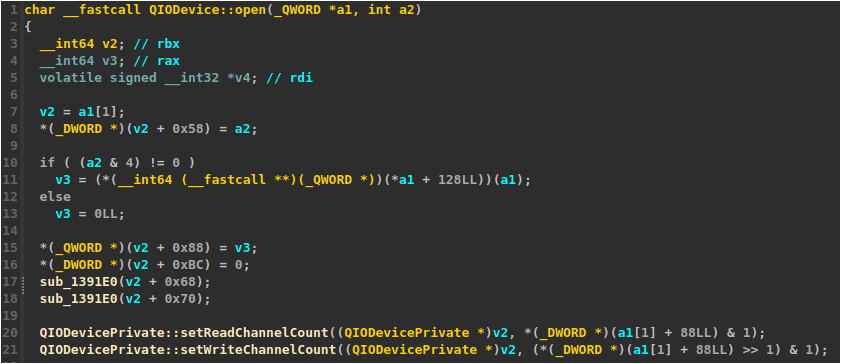

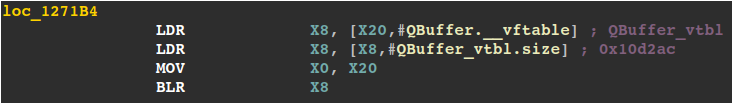

After applying Symless’s auto-analysis, the pseudocode becomes:

QIODevice::open after Symless’s pre-analysis.

The QIODevice and QIODevicePrivate structures were created and applied. Symless also reconstructed QIODevice’s virtual table (QIODevice_vtbl). This enables IDA to resolve the virtual call at line 11, which happens to be the QIODevice::size() method.

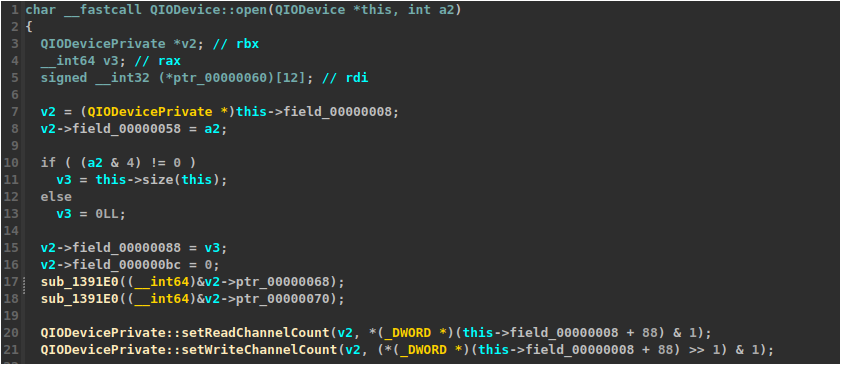

Symless also typed disassembly operands for every structure field access. For example the three instructions involved in calling QIODevice::size() were typed like this:

QIODevice::open disassembly operands typed by Symless.

Typing a disassembly operand in IDA creates a cross-reference between a structure field and the instruction that accesses it. This allows for easy access to every uses of a field from the field’s xrefs panel.

Apart from creating structures, Symless only alters the database in two ways: by typing the disassembly operands and by typing function arguments. It does not directly type or modify the pseudocode. In our example the first argument

a1 was typed into a QIODevice pointer by Symless, but

v2 (a simple local variable) was effectively typed by IDA’s own analysis. We trust IDA to synchronize its pseudocode with the types we applied in the disassembly.

Limitations

As explained previously, the most complex part of this automatic analysis is handling conflicts on related structures. As a result the auto-analysis is subject to three main types of errors:

- Duplicates: one structure may be created multiple times;

- Wrongly merged structures: Symless may incorrectly identify two or more structures as duplicates and merge them;

- Wrongly typed function arguments or disassembly operands: when multiple structures are candidates for typing, the wrong one may be selected as the common base.

To illustrate this last point, let’s examine a failure in our QtCore example. Here Symless reconstructed the following QAbstractAnimation and QAnimationGroup classes:

struct QAbstractAnimation { // sizeof=0x10

QAbstractAnimation_vtbl* __vftable;

uint64_t field_00000008;

};

struct QAnimationGroup { // sizeof=0x10

QAnimationGroup_vtbl* __vftable;

uint64_t field_00000008;

};Our data-flow analysis showed that instances of both classes can be passed as the same function arguments, indicating that they are related. Indeed, QAnimationGroup inherits from QAbstractAnimation, but Symless does not know that.

Because some virtual methods of QAbstractAnimation appear in both QAbstractAnimation and QAnimationGroup virtual tables, both classes were propagated in these methods. When typing those methods, Symless has to choose between the two classes. Finding the least-derived class is difficult because they have the same size and their virtual tables are also the same size. The less-accurate heuristics we use then decided that QAnimationGroup was the base class. Consequently, these virtual methods were typed with the wrong structure. One of these methods is QAbstractAnimation::setDirection:

__int64 __fastcall QAbstractAnimation::setDirection(QAnimationGroup* this, int a2);These errors produced by Symless’s auto-analysis must be manually repaired by the user. In some samples, the number of errors may outweigh the benefits of the analysis. In response to these limitations, we introduced a second, less automated operating mode that prompts the user to specify both the structure to build and the entry point to use. Asking the user prevents from typing code with the wrong structure.

Plugin mode

Symless’s second operating mode is an interactive plugin within IDA’s GUI. Using this plugin, the user can rebuild a structure from an entry point of their choosing. Data-flow analysis is performed from this unique entry to rebuild the structure.

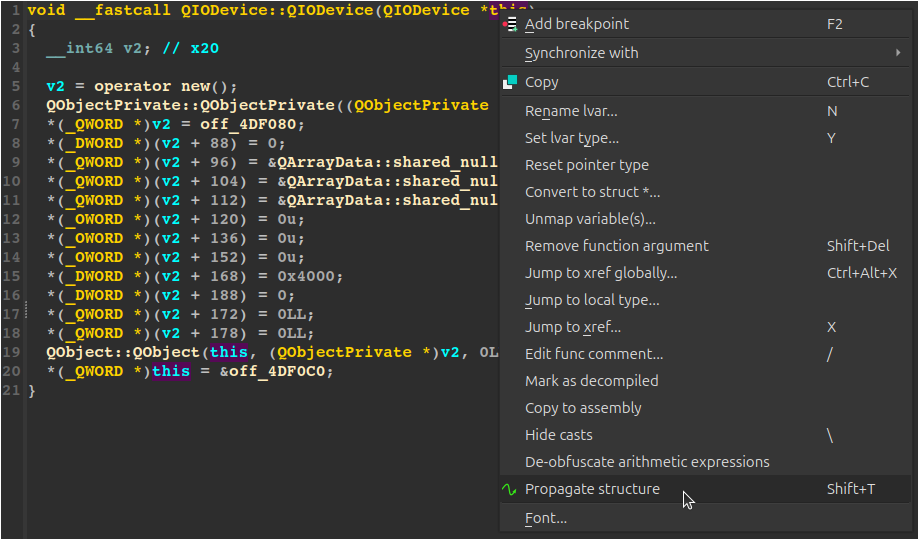

To illustrate, suppose we are again reversing QtCore, but did not run the pre-analysis. After stumbling on the QIODevice class, we want to reconstruct it and its virtual table automatically. For this, we place ourselves in its constructor, where it is initialized. From there, we select an entry line for the data-flow and use the “Propagate structure” option from the context menu that opens on right-click:

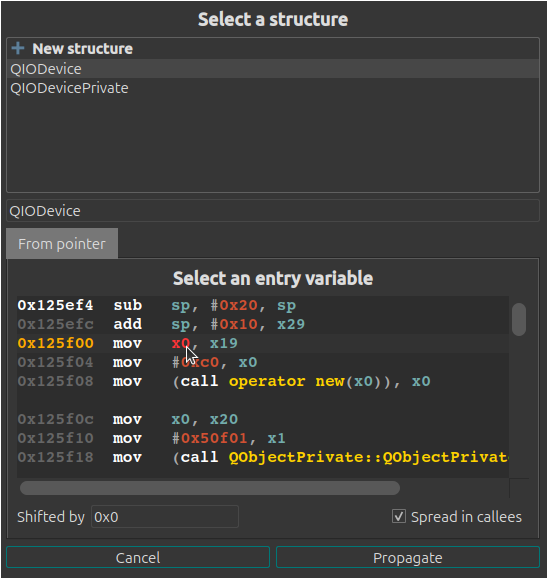

In this example, the selected entry point is the function prototype, since we want to propagate its argument from the beginning. The following form will appear:

This form requires the following information:

- the name of the structure to build: either an existing structure to complete or a new structure;

- an entry point for the data-flow: a microcode register known to hold a pointer to the structure.

Here, we select the QIODevice structure and, for the entry point, we choose the first appearance of the

x0 register, which holds the function’s first parameter.

You may wonder why we need to select the entry point again after clicking it in the pseudocode. To this day, IDA’s API does not provide a reliable way to map a pseudocode variable or disassembly operand to the corresponding microcode operand, so we ask the user to select it again. This requires the user to read and understand the microcode to some extent. It is however usually not difficult to figure out, even with limited microcode knowledge.

Two additional options are available:

- “Shifted by” allows to specify, in case of a shifted pointer, the amount of the shift;

- “Spread in callees” determines whether the analysis should also explore called functions and discovered virtual methods.

After hitting the “Propagate” button, QIODevice will be reconstructed from the given entry point. Its virtual table, loaded after the entry point, will be identified and reconstructed. All virtual methods are also analyzed, as “Spread in callees” was checked. If we look at the reconstructed QIODevice_vtbl fields, we find our previous size() virtual method with a cross-reference on it, showing it is indeed used in QIODevice::open().

This interactive plugin allows to reconstruct a structure and its virtual tables in a few clicks, as well as applying cross-references in the code traveled by the data-flow. This greatly reduces the back-and-forth navigation between the local types and code views required in vanilla IDA when making structures and placing cross-references. With the plugin handling those tasks, you can focus on naming and typing fields, which can be done directly from the pseudocode view.

This example demonstrated the creation of a new structure. Completing an existing structure is also possible: in this case, Symless will only fill the structure’s gaps and apply cross-references. Anything previously typed by the user will remain unchanged. It is especially useful for applying cross-references on new pieces of code that were not reached by previous analyses.

Conclusion

Whether used as an automatic pre-analysis or as an interactive plugin, Symless greatly simplifies the often time-consuming process of reconstructing structures and placing cross-references in IDA.

You can find the latest architecture-agnostic version on our GitHub, along with installation instructions. It supports IDA version 8.4 or superior. If you are a daily IDA user, we invite you to give it a try. Ideas for improvement and bug reports are welcome.