ARM TrustZone: pivoting to the secure world

- Discovery of two vulnerabilities in secure world components

- Exploitation to get code execution in a trusted driver, while not having a debugger for this obscure environment

- Leverage of aarch32 T32 instruction set to find nice stack pivots

- Turning an arbitrary write into an arbitrary code execution

The hidden world beneath Android

The story starts where one of the previous stories you have heard about Android ends, with arbitrary code execution in both userland and kernel. Let’s assume we have defused SELinux, bypassed seccomp limitations and have full privileges over Linux kernel. What could we do next?

While Android lives in plain sight, the secure world lives in its shadow. Let us put light on it! First, let’s coin a few terms:

- ARM TrustZone: security extensions that ship with ARM v7-A and v8-A. They basically allow the hardware to be partitioned in two: a normal and a secure worlds. In this model, the secure world embeds the most privileged exception level,

S-EL3, and secure OS,S-EL1, holds a powerful hand on the hardware devices - Trusted Execution Environment: aka TEE encompasses the applets, libraries and operating system living in the secure world

- Samsung Knox: a set of trusted components and normal world application components, such as Android apps and libraries. The terms “secure” and “trusted” are swappable for the rest of the article. It indicates a small, mastered TCB hosted in a secure execution environment

- TEEgris: Samsung Trusted OS that ships some Exynos-based devices. In the past, Samsung used to ship with Kinibi, a different trusted OS which has been the subject of security publications. Even Samsung models may ship with Qualcomm SoCs, and its own trusted OS called QSEE. High level descriptions of various TEE and their vulnerabilities can be found in SoK

TEEgris information is rather scarce on the Internet, we have only found a few sources: Federico menaniri @RISCURE, who exploits several vulnerabilities to gain secure memory write from normal world and Alexander tarasikov, who emulates secure boot using qemu and performs afl fuzzing of trusted applets

Trusted applets: applications that run in the TEE, to provide additional security protections against compromise in the normal world. For example, quoting Google Android documentation:

Android applications concerned by security may use Android keystore to save their sensitive cryptographic keys to be compromised in the normal world

For the rest of the article, the device we used is SM-J330FN, with early 2019 firmware J330FNXXU3BSA2_J330FNXEF3BSA2_XEF. It ships Exynos7570 SoC, which is based on ARMv8-A design. Samsung has brought to our attention the firmwares based on version Android 12 (or upper) no longer contain the vulnerabilities we present here. More details will be found in sections describing vulnerabilities.

How do normal world applications talk to the secure world

The single software component able to switch the processor state between normal and secure is the trusted firmware operating at EL3. Code running at lower exception levels can use smc instructions to trigger it. As this ARM instruction is not accessible from EL0, giving normal world applications access to the TEE will require EL1 support. For our case study:

- a userspace daemon

tzdaemonhas the adequate SELinux profile to access the device/dev/tz_wormhole; - kernel-side,

/dev/tz_wormholeimplements EL3 triggering mechanism together with sanitization.

The source code of tz_wormhole is located in drivers/misc/tzdev in Samsung’s Android kernel sources.

TEEGris is the S-EL1 component, and features are brought by the trusted applets, living in S-EL0.

Finding the trusted applets

This is not the case for all TEE designs, but we are lucky this time. The normal world, which we have total control of, stores trusted applets as files. For our device, those files are in /system/tee/.

j3y17lte:/system/tee $ ls -lR

.:

total 6736

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 67121 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00000000dead

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 298529 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000534b4d

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1895418 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-0000534b504d

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 95561 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00535453540a

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 85969 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00535453540c

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 218181 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00535453540d

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 59405 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00535453540f

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 85785 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-0053545354ab

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 615917 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00575644524d

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 23765 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-474154454b45

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 109985 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-4b45594d5354

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 393312 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-505256544545

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 571553 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-534543445256

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 162133 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-534543535452

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 789777 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-564c544b5052

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 47333 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-582f-586d3efb39b4

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 2008-12-31 16:00 driver

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1344367 2008-12-31 16:00 startup.tzar

./driver:

total 28

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 17217 2008-12-31 16:00 00000000-0000-0000-0000-00535453540b

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 6425 2008-12-31 16:00 18d9f073-18a5-4ade-9def-875e07f7f293_

Files named using an UUID sheme embed a genuine ELF ARM32 binary:

$ hexdump -C 00000000-0000-0000-0000-534543535452 00000000 53 45 43 32 00 02 75 10 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 |SEC2..u..ELF....| 00000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 00 28 00 01 00 00 00 |..........(.....| 00000020 74 17 01 00 34 00 00 00 f0 71 02 00 02 02 00 05 |t...4....q......| ... ELF ARM32 ... ... 17 73 61 6d 73 75 6e 67 5f 64 72 76 3a 73 61 6d |.samsung_drv:sam| ... 73 75 6e 67 5f 64 72 76 01 00 3e bb aa 17 58 1d |sung_drv..>...X.| ... ... 30 1e 06 03 55 04 03 14 17 73 61 6d 73 75 6e 67 |0...U....samsung| ... 5f 64 72 76 3a 73 61 6d 73 75 6e 67 5f 64 72 76 |_drv:samsung_drv| ... 30 82 01 22 30 0d 06 09 2a 86 48 86 f7 0d 01 01 |0.."0...*.H.....|

Embedded ARM32 ELF files can be carved out of their containers, and loaded with IDA. The additional data, which isn’t part of the ELF, most likely contains a signature, to ensure integrity in case of normal world corruption.

/system/tee/startup.tzar contains a part of Secure World userspace files. The name looks like a tar archive, indeed it is an archive format, documented by Alexander tarasikov.

The archive decompresses to:

$ tree startup_tzar

├── startup_tzar

│ └── bin

│ ├── 00000004-0004-0004-0404-040404040404

│ ├── 00000005-0005-0005-0505-050505050505

│ ├── 00000006-0006-0006-0606-000000000001

│ ├── 00000006-0006-0006-0606-000000000002

│ ├── arm

│ │ ├── libc++.so

│ │ ├── libdlmsl.so

│ │ ├── libmath.so

│ │ ├── libpthread.so

│ │ ├── libringbuf.so

│ │ ├── libtee_debugsl.so

│ │ ├── libteesl.so

│ │ ├── libteesock.so

│ │ └── libtzsl.so

│ └── libtzld.so

Overall, the archive contains:

- userspace libraries, in

bin/arm, likelibtzsl.so, andlibteesl.so. Symbols point to the TEE GlobalPlatform API, which is documented online. Those libraries are true ARM32 ELF files, without the header and footer we have observed above for trusted applets and drivers; - the dynamic linker,

libtzld.so, again, a plain ARM32 ELF file.

All in all we have found trusted applets, trusted drivers and trusted libraries. Let’s analyze them.

Typing GlobalPlatform TEE API

First we take a look at libteesl.so. It provides the implementation of tons of functions matching the pattern TEE_*. The curious reader might consult TEE GlobalPlatform documents for more information: they define a set of APIs, offered by TEE for trusted applets to execute. For applets to run on a TEE, they need to export a few functions. The set of APIs offered to applets is extensive, including using TCP/IP sockets via a normal userspace daemon. Back to libteesl.so, this is the implementation following the API. In order to help the reverse engineering of trusted components, we have developed an IDA type library:

- adapted TEE GlobalPlatform headers are compiled using Hexrays’s

tilibto buildtee_arm.til, to be copied into${IDA_HOME}/til/arm; - The same headers are processed using

pycparserto generate function signatures, and statically map a function name to a type info. The output is a Python scripttee_arm.py, that can be launched on a loaded binary to type functions.

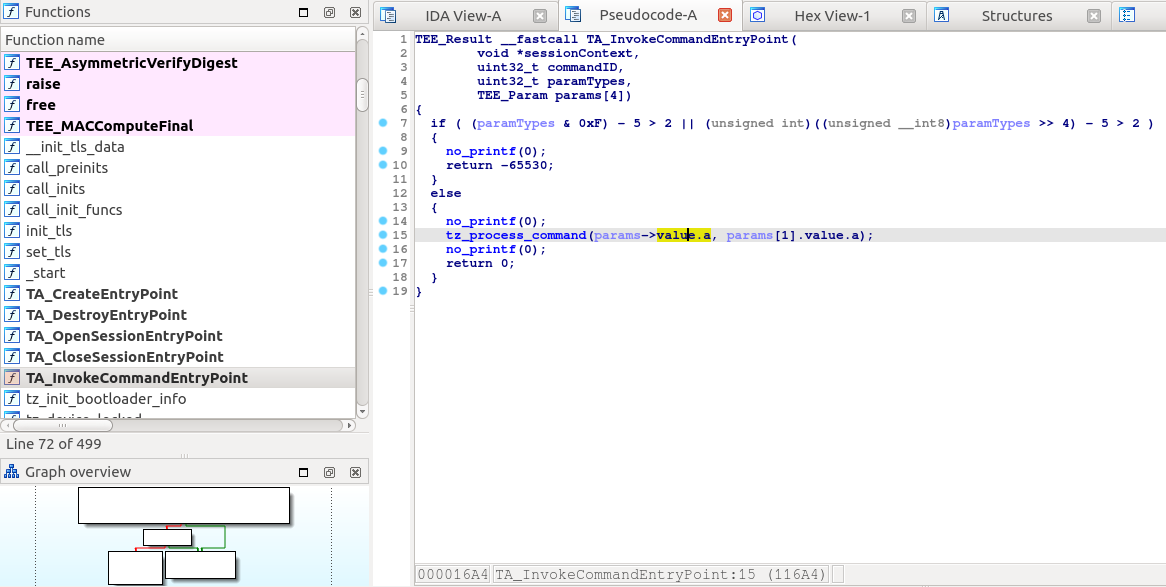

IDA is now capable of understanding the TEE API facet of trusted applets and drivers:

We now have a nice environment to perform static analysis of the keymaster trusted applet. It is named 00000000-0000-0000-0000-4b45594d5354 in tzar archive. Note that hexlify(b'KEYMST') == b'4b45594d5354'

Gaining control of KEYMST trustlet

Identifying entry points of a trusted applet

GlobalPlatform TEE API defines five callbacks to interact with a trusted applet:

TA_CreateEntryPointandTA_DestroyEntryPointare called when the trusted applet is created and destroyedTA_OpenSessionEntryPointandTA_CloseSessionEntryPointare called when a normal world application opens and closes a session with itTA_InvokeCommandEntryPointis called when a normal world application sends a request to it: this function will hold a dispatch logic based on the request code. Once a normal world has created a session with the trusted applet, it can perform several commands, and then close the session

Note that the main function is not located in a trusted applet binary, but is in libteesl.so. It performs initialization of the trusted applet then loops to process messages received over POSIX message queues. The exported functions are then called by the teesl library upon reception of suitable messages.

The vulnerability: vanilla stack overflow

Having the binary at hand for static analysis, let us first look at security hardening:

$ pwn checksec KEYMST

[*] 'KEYMST'

Arch: arm-32-little

RELRO: No RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x10000)

Starting with TA_InvokeCommandEntryPoiny, we quickly jump to tz_process_command, and after a while end up in a small function doing a weird memcpy:

__int64 hal_rsa_key_get_pub_exp(hal_rsa_key *a1)

{

size_t pub_exp_size; // r2

char *v2; // r1

__int64 v4; // [sp+0h] [bp-18h] BYREF

pub_exp_size = a1->pub_exp_size;

v2 = (char *)&a1->content + a1->pub_exp_offset;

v4 = 0LL;

memcpy(&v4, v2, pub_exp_size); /* pub_exp_size is controlled by normal world app */

return v4;

}

This function is called when importing a PKCS8 formatted RSA private key. The public exponent of the RSA key, which is an attacker controlled value, is copied onto the stack. While legitimate public exponents are generally small, the key format brings no guarantee that its value fits in a 64 bits integer. The format of the private key by itself does not have any restrictions, but the implementation does verify some assumptions about the key, among which the size of the public exponent, that should be less than 512 bytes. All in all, we can overwrite up to 0x200-8=0x1f8 bytes on the stack.

To reach this vulnerability, we still have to pass through a number of function calls, and each function processes parts of the parameter. This means we need to craft the input buffer to go through:

TA_InvokeCommandEntryPoint: TEE API entry point. Input buffer embeds a type, which is verifiedtz_process_command,km_import_key: those functions parse and assert parameters of the public key. We will not detail the verifications done, as they are not complex to get aroundkm_rsa_key_get_pub_exp: jumper tohal_rsa_key_get_pub_exp, which overflows the stack

As we do not have any working input buffer, we have to build a correct one from scratch. However, there is no way to debug the secure world on a production device, so as to identify the code paths taken when processing a request.

Building a TEEGris emulator on top of qiling

To enhance our dynamic analysis capabilities, we have implemented a TEEGris emulator based on qiling. The device will only be used to test our cooked payloads, and verify meaningful effects. We have not opted to follow Alexander Tarasikov’s track, since we want to be able to add dynamic analysis fragments of code, and not recompile qemu each time.

We have chosen qiling for the following reasons:

qilingis written in Python, and allows for easy hooking of instructions and memory. As we emulate, we can build advanced analysis that we would be unable to get on real hardware using a debug interface, like looking for uninitialized stack variablesqilingalready has POSIX syscall emulation, though the mecanism will need to be adapted to TEEGris syscalls flavourqilingsupports snapshot and restore, so we can bootstrap a trusted applet, snapshot it, and quickly restore it later to further explore from the restored state

To know more about the TEEGris system calls, we analyze libtzsl.so:

To find the system call convention: by peeking at a few wrappers, here we show

syslogwrapper, we can make the assumption thatr7holds the system call number, and arguments are passed throughr0tor6:.text:0000BDC8 syslog ; CODE XREF: j_syslog+8↑j .text:0000BDC8 ; DATA XREF: LOAD:00001338↑o ... .text:0000BDC8 PUSH {R4,R7,R11,LR} .text:0000BDCC MOV R7, #0x12 .text:0000BDD0 ADD R11, SP, #0xC .text:0000BDD4 SVC 0 .text:0000BDD8 CMN R0, #0x1000 .text:0000BDDC MOV R4, R0 .text:0000BDE0 BLS loc_BDF4 .text:0000BDE4 RSB R4, R4, #0 .text:0000BDE8 BL j_get_errno_addr .text:0000BDEC STR R4, [R0] .text:0000BDF0 MOV R4, #0xFFFFFFFF .text:0000BDF4 .text:0000BDF4 loc_BDF4 ; CODE XREF: syslog+18↑j .text:0000BDF4 MOV R0, R4 .text:0000BDF8 POP {R4,R7,R11,PC} .text:0000BDF8 ; End of function syslogTo find the system call numbers: we have written a Python script that automates the job of spotting

r7initialization followed by supervisor call, by looking back a few instructions oncesvc #0has been found. Once a system call pattern has been detected, we lookup the last exported function preceding it. A few corner cases have to be hand resolved, as the logic is a bit too simplistic.

$ ./extract-syscalls.py startup_tzar/bin/arm/libtzsl.so

syscalls = {

# sysno: (name, start of function, address of svc #0)

1: ('thread_create', 0xbe70, 0xbed4),

2: ('thread_wait', 0xbf5c, 0xbf68),

3: ('mmap', 0x52fc, 0x5380),

4: ('munmap', 0x5bbc, 0x5bc8),

5: ('epoll_ctl', 0x33b0, 0x33bc),

6: ('close', 0x2c78, 0x2c84),

7: ('open', 0x5bf0, 0x5c10),

8: ('read', 0x6bd0, 0x6bdc),

...

Back to qiling, we had to modify os and linker layers:

- os : analyzing

libtzsl.sohas yielded system call numbers and names. We made sure to emulateopenandmmapproperly at first, then implemented additional system calls when needed - linker: OS passes information about the started binary through an auxiliary vector. This information is processed in the early life of the dynamic linker. The linker expects a hardwired order of the values in the auxiliary vector

- os: even though secure kernel looks POSIX, it uses weird semantics:

ioctl(fd, 0, 0)on a file backed descriptor returns the size of the file, just likefstat(fd, &stat); return stat.st_size;would

Glue TEEGris system calls to already emulated qiling system calls

To add new system calls, we use Qiling.set_syscall. Rather than rewrite every system call, we prefer to wire each given system call number to a Linux syscall that is already emulated in qiling: we use Qiling.set_syscall and we lookup the original implementation with:

self.original_handlers = {}

map_syscall = utils.ql_syscall_mapping_function(self.ostype)

for x in range(1, 400):

y = map_syscall(self, x)

# syscall is not already handled by qiling

if y is None: continue

# resolve handler

handler = None

if y in dir(posix_syscall):

handler = getattr(posix_syscall, y)

elif y in dir(linux_syscall):

handler = getattr(linux_syscall, y)

assert(y.startswith('ql_syscall_'))

name = y[11:]

The new handler can rely on the original qiling implementation, either to simply call it, or to adapt the system call arguments to TEEGris expectations.

Map filesystem names to custom handlers

While implementing open, we have observed TEEgris uses URIs as filenames. Those filesystem names will not be handled correctly during qiling emulation, as they cannot be mapped to the Linux host filesystem. Fortunately, qiling anticipates that need, and users can add custom I/O easily, through QlFsMappedObject:

self.add_fs_mapper('sys://proc', Fake_sys_proc())

A toy implementation is as simple as:

class Fake_sys_proc(QlFsMappedObject):

def read(self, size):

return b'\x01'

def fstat(self):

return -1

def close(self):

return 0

This template is easily extensible as a stateful behavior, and is needed for some reasons. While QlFsMappedObject defines an ioctl method, we have opted to implement it in the system call handler. We need to write to the address given in the third parameter of the ioctl system call, which is not directly feasible using the QlFsMappedObject interface.

Triggering the vulnerability

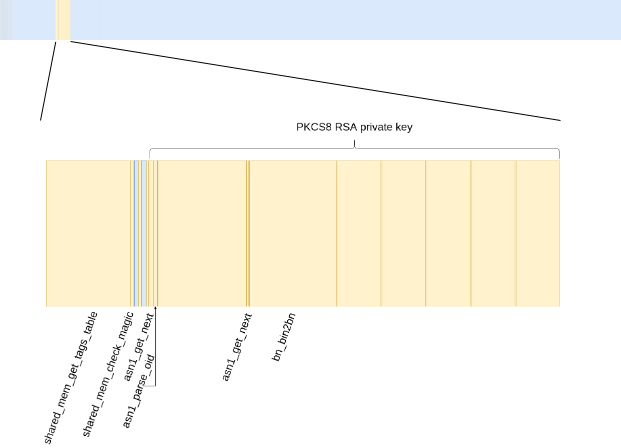

Thanks to our emulator, KEYMST can be loaded. However, we do not have a request example capable of reaching the vulnerability location. To help us find a correct message, we have created a feedback loop: once in main processing loop, we map our input parameter and call to TA_InvokeCommandEntryPoint. qiling then generates a drcov coverage of the execution, with which we feed the IDA and lighthouse plugin. Rinse and repeat, and we have successfully crafted an input complying with the checks made and allowing us to control most of the input shared buffer. The input buffer shown below is 87856 bytes long, and the yellow bars indicate memory areas read while processing the normal world request:

The input buffer is largely unaccessed: we can freely use it to embed controlled information we will use later, during exploitation. The yellow zones, accessed and mostly checked are the PKCS8 RSA private key and a “tags table”.

Building a ropchain to pivot to a subsequent ropchain

The stack overflow is nice, and the initial stack space we can overwrite is small. As we gain code execution in the secure world, we would also want to observe it from the inside, from the point of view of a trusted applet. It is important to test system calls behaviors, and verify assumptions we have made regarding non POSIX system calls. As we fully control a large part of the input buffer, we build a first ropchain which will copy a second, larger, embedded ropchain, and pivot to it:

- First, a bootstrap ropchain, which fits in

0x1f8bytes:- Save register content before losing their initial values. There is a suitable space in

KEYMST.bss - Allocate a new stack at a fixed address. Make the trusted applet do

mmap(0xdead000, 0x8000, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_FIXED|MAP_ANONYMOUS). The chosen address is arbitrary but for robustness sake, we could have used the TEEGris specific system call that verifies memory range existence and permissions - Copy a large part of input shared memory to the newly allocated stack

- Save register content before losing their initial values. There is a suitable space in

- Second, an embedded ropchain. We have arbitrarily chosen to split the buffer into

0x5e00bytes of stack and0x2000bytes of data. As the trusted applet isaarch32, instruction set includesload multipleakaldminstructions. We have selected[KEYMST:thumb] 0x1975c: ldm.w r4, {r0, r1, r2, r3, r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, sb, fp, sp, lr, pc}. This instruction is a T32 instruction that spreads over 4 bytes. We have observedROPgadget,ropperandxropdo not output this gadget, even though it is legitimately classified as a Jump Oriented Programming gadget. The curious reader can read the details in Annex T32 ISA The embedded payload is composed of three parts, again we have arbitrarily chosen the limit between data and stack zones:[0x100-0x200]: new register values[0x200-0x6000]:spis set to0xdead000+0x200, which will be top of the stack just afterldm.wexecutes[0x6000-0x8000]: data used by embedded payload As we have mapped our input buffer to a fixed address, we can compute the address of our copied data in the target program, and easily reference input or output parameters we want to supply as reference to system calls.

- Finally, as we have backed up the initial register values in step 1, we could restore processor context to a deeper call frame, to return in the

mainloop oflibteesl.so, safely waiting for new messages to process.

Interact with the secure kernel

We now have the ability to ROP into a trusted applet. This means we can perform secure system calls on behalf of it. We have explored the secure userspace environment, looking for ways to gain arbitrary code execution:

- open a file for writing, save arbitrary code, open it for reading, map it as RX: it does not work, because files cannot be opened with write access mode. It is possible to map existing files as RX though, even at a fixed address. We can enrich our accessible gadgets set that way, for example by loading

libteesock.sowhich contains indirect branches of all kinds - map anonymous memory as RW, remap it as RX: there is no system call to perform the equivalent of

mprotect. We have tried to usemmapto do the same, but none of our attempts worked - create a socketpair, and map the content as RX: we have identified the only supported socket type, domain, and family. Reversing the secure kernel shows that this type of file descriptor supports

mmapsystem call. But the mapping failed while asking forPROT_EXEC - use

TEES_ExecuteCustomHandlerandTEES_RegisterCustomHandlersystem calls: though their names look interesting, executing them in the context ofKEYMSTfails, and the system call returns-1,EPERMThe trusted drivers we have seen instartup.tzarare not directly reachable from normal world. Thanks to this vulnerability, we can makeKEYMSTcommunicate to the trusted drivers, and explore the drivers features.

Impacted versions

Samsung has confirmed the vulnerability affects KEYMST, that only exists in Android P firmwares. More recent versions are not affected by this vulnerability.

Expanding control over trusted driver

Motivation: gain code execution in secure kernel

Intuitively, we expect a trusted driver to have more privileges than a trusted applet. Let’s start with analyzing the driver contained in the startup archive.

The static analysis of driver/00000000-0000-0000-0000-00535453540b in startup.tzar reveals it calls an awkward system call TEES_ExecuteCustomHandler:

int __fastcall timautil_sram_recovery_read(int a1)

{

int result; // r0

int v2; // r2

int v4[3]; // [sp+8h] [bp-24h] BYREF

int v5[4]; // [sp+14h] [bp-18h] BYREF

int v6; // [sp+24h] [bp-8h]

v6 = -3;

TEE_MemFill(v4, 0, 28);

v4[0] = 130;

v4[1] = 5;

v4[2] = 0;

printf("@echeck: result: %d, cmd_ret0: %d\n", v6, v5[0]);

v6 = TEES_ExecuteCustomHandler(0xB2000202, v4);

printf("##echeck: result: %d, cmd_ret0: %d\n", v6, v5[0]);

result = TEE_MemMove(*(_DWORD *)(a1 + 8), v5, 4);

if ( v6 )

return printf("Execute Custom handler failed to get mode : retval %d (%08x)\n", v6, v2);

return result;

}

The name looks promising, there even exists a system call named TEES_RegisterCustomHandler which we could leverage to perform some sort of install of a new handler. But first, let’s analyze the booting image sboot.img. It contains the image of the secure OS, TEEGris, which will be loaded and run at boot. Annex Secure reconnaissance describes how to extract OS from it and perform static analysis of system call implementation.

We see that a verification is carried out on the caller process:

__int64 __fastcall sel1_syscall_TEES_ExecuteCustomHandler(unsigned int a1, __int64 a2)

{

_BYTE v5[56]; // [xsp+28h] [xbp+28h] BYREF

if ( !sub_FFFFFFFFF01059C4(0x12u, 1i64) ) // looks like a verification

return -1i64;

if ( (unsigned int)j_sel1_do_copy_from_userspace((__int64)v5, a2, 56i64) )

return -14i64;

sel1_perform_smc(a1, v5, 0x40000000);

if ( (unsigned int)j_sel1_do_copy_to_userspace(a2, (__int64)v5, 56i64) )

return -14i64;

return 0i64;

}

This verification is the same as the verification performed when calling TEES_RegisterCustomHandler:

__int64 __fastcall sel1_syscall_TEES_RegisterCustomHandler(unsigned __int16 a1, __int64 a2, __int64 a3, int a4)

{

BOOL v8; // w0

__int64 v9; // x1

int v11; // w24

__int64 v12; // x0

unsigned __int64 v13; // x23

__int64 v14; // x0

_QWORD *v15; // x25

int v16; // w19

unsigned int v18; // [xsp+5Ch] [xbp+5Ch] BYREF

v8 = sub_FFFFFFFFF01059C4(0x12u, 1i64); // the very same verification

v9 = -1i64;

if ( v8 )

{

v9 = -22i64;

if ( (unsigned __int64)(a3 - 1) <= 0x3FFFF && a2 != 0 )

{

v11 = sub_FFFFFFFFF012413C(

*(_QWORD *)(((_ReadStatusReg(ARM64_SYSREG(3, 0, 13, 0, 4)) - 1) & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFE000ui64) + 0x68) + 468i64,

16i64);

v18 = (unsigned __int64)(a3 + 4095) >> 12; // round to page size

v12 = sub_FFFFFFFFF010EC00(&v18, 0i64, 0);

v13 = v12;

v9 = -12i64;

if ( v12 )

{

v14 = sub_FFFFFFFFF010EA34(v12);

v15 = (_QWORD *)v14;

if ( !v14 || (unsigned int)j_sel1_do_copy_from_userspace(v14, a2, a3) ) // copy from userspace

{

v16 = -14;

LABEL_11:

sub_FFFFFFFFF010ED0C(v13, v18);

return v16;

}

v16 = sub_FFFFFFFFF01194D4(a1, v11, v15, v18, a4);

v9 = 0i64;

if ( v16 )

goto LABEL_11;

}

}

}

return v9;

}

It means that if a process is allowed to call TEES_ExecuteCustomHandler, it may also be authorized to call TEES_RegisterCustomHandler. The function which performs verification is sub_FFFFFFFFF01059C4. The target only has one active driver. This driver looks promising, at it uses a system call that requires the same privilege level as the system call which registers a handler inside the secure kernel. We will call the driver STST for the rest of the article, based on the UUID naming scheme shown earlier. The driver binary has the same type as KEYMST binary. In particular, it is also a trusted applet, with exported TEE functions.

Examining driver entry points

Driver shares the hardening features of STST:

$ pwn checksec STST

[*] 'STST'

Arch: arm-32-little

RELRO: No RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x10000)

The driver registers itself with TEES_RegisterDriver, called when the driver is loaded:

struct driver {

int (*open_f)();

int (*ioctl_f)();

...

};

static struct driver drv;

int TA_CreateEntryPoint()

{

int v2; // [sp+4h] [bp-8h]

drv.open_f = drv_open;

drv.ioctl_f = drv_ioctl;

v2 = TEES_RegisterDriver(&drv);

if ( v2 )

{

printf("register_driver failed, ret = %d\n", v2);

return -65536;

}

else

{

printf("TIMA Driver registered\n");

return 0;

}

}

The driver registers an ioctl callback, which may be called from the vulnerable KEYMST applet. A few ioctl commands can be performed on this driver, among which two eventually call log_msg:

int log_msg(int a1, int a2, int a3, int a4, char *format)

{

TEE_MemFill(&g_entry_ptr, 0, 0x80u);

byte_23118 = 1;

byte_23119 = 0;

byte_2311A = 0;

byte_2311B = 0;

g_entry_ptr = 15;

byte_23115 = 39;

byte_23116 = 0;

byte_23117 = 0;

snprintf(s, 0x77u, "%s", format);

log_add_entry(a1, a2, a3, a4, &g_entry_ptr);

return printf(format); /* format string controlled by compromised trusted applet */

}

The format argument comes from the ioctl argument, but is not located on the stack, meaning that we cannot directly control printf arguments with our input buffer. In the next part, we devise a strategy to gain arbitrary read and write.

Gaining arbitrary read and write

The vulnerability can be used several times in a row, as the driver process does not exit between calls. We have chosen to alter the stack in a part deep enough to not be reused in between two ioctl calls.

We have identified a chain of three stack words that point to each other:

In the diagram above, the value K will not be altered by the program between multiple ioctl calls, giving us the ability to fully control its value.

To put an arbitrary address a instead of K above, we write it byte by byte, overwriting the low byte of J each time with an incrementing value:

Once we are able to put an arbitrary address on the stack, we can simply turn printf to our advantage using %pU or %n variants.

Since the driver is not PIE, the .got section is at a fixed location in memory. Leaking two words of .got, we leak the randomized addresses of libteesl.so and libtzsl.so. A question remains: how to turn a sequence of well-balanced writes to code execution?

Gaining arbitrary code execution

Using dynamic memory hooks like __malloc_hook is not an option here, as libtzsl.so heap implementation does not have a hooking mechanism. Overwriting a return address in the stack is still possible, but we have chosen to leverage a specific feature called custom printf format specifiers, which glibc implements. Luckily for us libtzsl.so also implements this juicy feature. In essence, it gives an application a way to dynamically register new format specifiers, by mapping a custom format, like %W to a user-specified function that will output the argument. The following function illustrates how a new custom specifier registers a callback:

int __fastcall register_printf_format(char a1, int a2)

{

int i; // r2

char *v3; // lr

int result; // r0

for ( i = 0; i != 10; ++i )

{

v3 = &custom_formats_tab[8 * i];

if ( !*((_DWORD *)v3 + 1) )

{

custom_formats_tab[8 * i] = a1;

result = 0;

*((_DWORD *)v3 + 1) = a2;

return result;

}

}

return 1;

}

This newly registered format specifier may then be used with printf. Backend printf implementation is complex and large, but the interesting part is the following fragment, that loops through custom format specifiers:

...

LABEL_138:

v44 = 0;

while ( (unsigned __int8)custom_formats_tab[8 * v44] != current_fmtspec )

{

if ( ++v44 == 10 )

goto LABEL_141;

}

result = (*(int (__fastcall **)(unsigned int *))&custom_formats_tab[8 * v44 + 4])(¤t_pos);

if ( result == 1 )

{

LABEL_141:

output_char((int)¤t_pos);

if ( *cur_fmt )

goto LABEL_146;

--cur_fmt;

goto LABEL_174;

}

if ( result >= 0 )

goto LABEL_174;

return result;

}

Upon custom function call, r12 points to the vasprintf pointer in libtzsl.so .got:

.got:0001F85C vsscanf_s_ptr DCD vsscanf_s ; DATA XREF: j_vsscanf_s+8↑r .got:0001F860 vasprintf_ptr DCD vasprintf ; DATA XREF: j_vasprintf+8↑r .got:0001F864 recvmsg_ptr DCD recvmsg ; DATA XREF: j_recvmsg+8↑r .got:0001F868 mq_open_ptr DCD mq_open ; DATA XREF: j_mq_open+8↑r .got:0001F86C __iwshmem_mmap_ptr DCD __iwshmem_mmap ; DATA XREF: j___iwshmem_mmap+8↑r .got:0001F870 close_ptr DCD close ; DATA XREF: j_close+8↑r .got:0001F874 raise_ptr DCD raise ; DATA XREF: j_raise+8↑r .got:0001F878 free_ptr DCD free ; DATA XREF: j_free+8↑r .got:0001F87C dword_1F87C DCD 0 ; DATA XREF: get_errno_addr↑o .got:0001F87C ; get_errno_addr+C↑o ... .got:0001F87C ; TLS-reference .got:0001F880 DCD 0 .got:0001F884 abort_handler_s_ptr DCD abort_handler_s ; DATA XREF: set_constraint_handler_s+24↑o .got:0001F884 ; set_constraint_handler_s+28↑r ... .got:0001F888 extra_mmap_flags_ptr DCD extra_mmap_flags .got:0001F888 ; DATA XREF: sub_3BBC+8↑o .got:0001F888 ; sub_3BBC+24↑r ... .got:0001F888 ; .got ends .got:0001F888 .data:0001F88C ; =========================================================================== .data:0001F88C .data:0001F88C ; Segment type: Pure data .data:0001F88C AREA .data, DATA .data:0001F88C ; ORG 0x1F88C .data:0001F88C off_1F88C DCD abort_handler_s ; DATA XREF: set_constraint_handler_s↑o .data:0001F88C ; set_constraint_handler_s+10↑o ... .data:0001F890 aUnknown DCB "UNKNOWN",0 ; DATA XREF: set_log_component+8↑o .data:0001F890 ; set_log_component+14↑o ... .data:0001F898 DCB 0

One may ask where does this value comes from. The reason is:

printfinternally usesvasprintf;- Both functions are in

libtzsl.so, hence have no reason to perform the branch via.plt; - But for a few reasons, we must branch through

.plt. Those reasons include the fact that the branch would not be a valid ARM instruction; - The veener can be found in

.plt, and it usesip, akar12, to perform the branch; - This value is left untouched in

ip, as it is only used to branch some internal functions. Since the.gotsection is overwritable we conclude driver exploitation with a call to[libteesl.so:thumb] 0x48f9a: ldm.w ip, {r0, r1, r3, r4, r5, r6, r8, sb, fp, ip, sp, pc}. This instruction allows us to perform a stack pivot and jump into a ropchain. Due to the constraints we have on.got, we cannot directly control juicy registers at first shot. For example, changingrecvmsgwill make the driver malfunction, as this function is used to receive ioctl calls. But we can take control ofspandpc, without causing a crash:.got:0001F85C vsscanf_s_ptr DCD vsscanf_s ; DATA XREF: j_vsscanf_s+8↑r .got:0001F860 vasprintf_ptr DCD vasprintf ; DATA XREF: j_vasprintf+8↑r <= ip .got:0001F864 recvmsg_ptr DCD recvmsg ; DO NOT TOUCH THIS .got:0001F868 mq_open_ptr DCD mq_open ; DATA XREF: j_mq_open+8↑r .got:0001F86C __iwshmem_mmap_ptr DCD __iwshmem_mmap ; DATA XREF: j___iwshmem_mmap+8↑r .got:0001F870 close_ptr DCD close ; DATA XREF: j_close+8↑r .got:0001F874 raise_ptr DCD raise ; DATA XREF: j_raise+8↑r .got:0001F878 free_ptr DCD free ; DATA XREF: j_free+8↑r .got:0001F87C dword_1F87C DCD 0 ; DATA XREF: get_errno_addr↑o .got:0001F87C ; get_errno_addr+C↑o ... .got:0001F880 DCD 0 .got:0001F884 abort_handler_s_ptr DCD abort_handler_s ; DATA XREF: set_constraint_handler_s+24↑o .got:0001F884 ; set_constraint_handler_s+28↑r ... .got:0001F888 controlled sp ; SAFE TO CHANGE .data:0001F88C controlled pc ; SAFE TO CHANGE .data:0001F88C ; set_constraint_handler_s+10↑o ... .data:0001F890 aUnknown DCB "UNKNOWN",0 ; DATA XREF: set_log_component+8↑o .data:0001F890 ; set_log_component+14↑o ... .data:0001F898 DCB 0

Luckily for us, libteesl.so and libtzsl.so have lots of gadgets we can use, and we have already leaked their base addresses.

Impacted versions

Samsung has confirmed the vulnerability affects STST. This privileged trusted applet ships with Android versions spanning from Android P to Android R. Please note that Android S and more recent are not affected by this vulnerability.

Conclusion

We hope you have enjoyed this trip to one of the Samsung variant of ARM secure world. Software is an inextinguishable source of vulnerabilities. ARM TrustZone is a nice feature, but it provides a segregation which is only as strong as the software components that run inside it. In our case, we have chained two vulnerabilities to potentially gain code execution in the context of the secure OS. Those two applets would have benefited from basic hardening measures such as stack cookie, PIE and RELRO. We hope to see you again for one of our next trips!

Ressources

Articles about TEEgris

- Reverse-engineering Samsung S10 TEEGRIS TrustZone OS

- Breaking TEE Security Part 1: TEEs, TrustZone and TEEGRIS, Breaking TEE Security Part 2: Exploiting Trusted Applications (TAs), and Breaking TEE Security Part 3: Escalating Privileges

- tzar unpack script

ARM system architecture

T32 ISA

Modern ARM processors support several instruction sets. Sticking to the most meaningful for us:

- ARM instructions which are 4-bytes instructions;

- Thumb instructions which are 2-bytes instructions, and thus provide higher code density. However, the ISA is not as rich than the ARM one.

Starting with ARMv7, ARM decided to extend Thumb ISA with Thumb2 instructions, which are 4-bytes instructions, to benefit from more compact machine code. Those instructions might look like legal ARM instructions, but they start at an address which is not a multiple of 4. Not all ARM instructions are supported, only a few selected ones are supported when in Thumb mode. Multiple load, or

ldm, is one of those. While Thumb does haveldminstructions, they do not allow to setpc, as the operand scope is too limited. Thumb2 holds powerful ARM variants, including the ability to setpc. Do note that in the latest version of the ARMv8 ISA, usingldmto setspcauses an unpredictable behaviour. Yet, we did try on our target device, and it just worked: the stack pivoted correctly. So when looking for gadgets in ARM code sections, it is useful to search for Thumb2 instruction. The following sample may help to spot the origin of the problem:

.section .text

.global _start

.arm

_start:

mov r0, r0

adr r0, gadget+1

bx r0

.byte 0x00, 0x00

.thumb

gadget:

.byte 0xe8, 0x94, 0xeb, 0xff

.byte 0xff, 0xeb, 0x94, 0xe8

Existing ROP tools - we have tested with ROPgadget, xrop and ropper - might miss it. This is mainly due to the way those tools work: they spot an interesting ending instruction, and then perform disassembly at a few backward places, trying to find a non-branching flow ending there. Looking at the tools one by one:

ROPgadgetdetects multiple load as a possible ending. But it is only detected when it starts with an address multiple of 4. As we have seen, Thumb2 allows such a gadget on an address multiple of 2, but not 4. If we specify--align 2option, then the gadget will be falsely detected as ARM - recall that Thumb2 is mainly ARM instructions. The instruction flow in which the instruction lives is Thumb however.ropperdoes not detect multiple load as possible ending;xropdetects multiple load as a possible ending. The disassembly engine, based on bfd libopcodes, supports Thumb and Thumb2 decoding. However, it fails to detect the gadget in our test binary. When applied to the sample above, the tools yield:> # The gadget will not be detected > ./ROPgadget.py --binary ../samples/ldm Gadgets information ============================================================ 0x00010058 : add r0, pc, #3 ; bx r0 0x00010044 : andeq r0, r0, ip, rrx ; andeq r0, r0, ip, rrx ; andeq r0, r0, r5 ; ... 0x00010048 : andeq r0, r0, ip, rrx ; andeq r0, r0, r5 ; andeq r0, r1, r0 ; ... 0x00010038 : andeq r0, r0, r0 ; andeq r0, r1, r0 ; andeq r0, r1, r0 ; ... 0x0001004c : andeq r0, r0, r5 ; andeq r0, r1, r0 ; mov r0, r0 ; add r0, pc, #3 ; bx r0 0x00010040 : andeq r0, r1, r0 ; andeq r0, r0, ip, rrx ; andeq r0, r0, ip, rrx ; ... 0x0001003c : andeq r0, r1, r0 ; andeq r0, r1, r0 ; andeq r0, r0, ip, rrx ; ... 0x00010050 : andeq r0, r1, r0 ; mov r0, r0 ; add r0, pc, #3 ; bx r0 0x0001005c : bx r0 0x00010054 : mov r0, r0 ; add r0, pc, #3 ; bx r0 Unique gadgets found: 10 > # The gadget will be detected as we force the alignment to Thumb alignment > ./ROPgadget.py --binary ../samples/ldm --align 2 Gadgets information ============================================================ 0x00010058 : add r0, pc, #3 ; bx r0 0x0001004c : andeq r0, r0, r5 ; andeq r0, r1, r0 ; mov r0, r0 ; add r0, pc, #3 ; bx r0 0x00010050 : andeq r0, r1, r0 ; mov r0, r0 ; add r0, pc, #3 ; bx r0 0x0001005c : bx r0 0x00010066 : ldm r4, {r0, r1, r2, r3, r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, sb, fp, sp, lr, pc} 0x00010054 : mov r0, r0 ; add r0, pc, #3 ; bx r0 Unique gadgets found: 6 > # The gadget will not be detected > Ropper.py -a ARMTHUMB -f ./ldm [INFO] Load gadgets from cache [LOAD] loading... 100% Gadgets ======= 0 gadgets found > # The gadget will not be detected > Ropper.py -a ARM -f ./ldm [INFO] Load gadgets from cache [LOAD] loading... 100% [LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100% Gadgets ======= 0x00010058: add r0, pc, #3; bx r0; 0x00010048: andeq r0, r0, ip, rrx; andeq r0, r0, r5; andeq r0, r1, r0; mov r0, r0; ... 0x0001004c: andeq r0, r0, r5; andeq r0, r1, r0; mov r0, r0; add r0, pc, #3; bx r0; 0x00010050: andeq r0, r1, r0; mov r0, r0; add r0, pc, #3; bx r0; 0x0001005c: bx r0; 0x00010054: mov r0, r0; add r0, pc, #3; bx r0; 6 gadgets found > # The gadget will not be detected > xrop -b 16 -r arm ./ldm > 0x50 0000 movs r0, r0 0x54 0000 movs r0, r0 0x58 0003 movs r3, r0 0x5c E12FFF10 vrhadd.u16 d14, d0, d31 _______________________________________________________________ > # The gadget will not be detected > xrop -b 32 -r arm ./ldm > 0x50 00010000 andeq r0, r1, r0 0x54 E1A00000 nop ; (mov r0, r0) 0x58 E28F0003 add r0, pc, #3 0x5c E12FFF10 bx r0 _______________________________________________________________

Secure reconnaissance

The firmware zip file contains multiple tar archives, among which the BL_ prefixed one contains sboot.bin which is the file used by BootROM to start the Secure World: it will contain TEEgris secure kernel. It can be encrypted, but it was not for our particular target.

sboot.bin is a flat file, and a few aarch64 system architecture facts help to analyze it:

- ARM bare metal boot: the use of ARM64 system registers to set up a system with multiple exception levels;

- the structure of the ARM64 exception vector table is singular and allows to be identified in a flat binary: aligned with

0x800, each vector is0x80bytes long.NOPpadding is used to fulfill the alignment constraint. Some entries are infinite loops that jump to self; - a well-identified exception vector serves supervisor calls made by inferior exception levels. This vector shall reach the dispatch logic that will call a specific function associated with the supervisor call identifier. The two possible interrupt vectors are

synchronous lower el using aarch64, at+0x400andsynchronous lower el using aarch32at+0x600. The secure kernel can be extracted from the firmware, and the system calls implementation analyzed.