Fuzzing Microsoft's RDP Client using Virtual Channels: Overview & Methodology

This article begins my three-part series on fuzzing Microsoft’s RDP client. In this first installment, I set up a methodology for fuzzing Virtual Channels using WinAFL and share some of my findings.

Other articles in this series:

- Fuzzing Microsoft’s RDP Client using Virtual Channels: Overview & Methodology

- Remote ASLR Leak in Microsoft’s RDP Client through Printer Cache Registry (CVE-2021-38665)

- Remote Deserialization Bug in Microsoft’s RDP Client through Smart Card Extension (CVE-2021-38666)

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Remote Desktop Protocol

- Fuzzing the RDP client with WinAFL: setup and architecture

- Fuzzing methodology

- Results

- Conclusion

Introduction

The Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) is a proprietary protocol designed by Microsoft which allows the user of an RDP Client software to connect to a remote computer over the network with a graphical interface. Its use around the world is very widespread; some people, for instance, use it often for remote work and administration.

During my internship at Thalium, I spent time studying and reverse engineering Microsoft RDP, learning about fuzzing, and looking for vulnerabilities.

The initial idea was to follow up on a conference talk from Blackhat Europe 2019. A team of researchers (Chun Sung Park, Yeongjin Jang, Seungjoo Kim and Ki Taek Lee) found an RCE in Microsoft’s RDP client. In particular, they found a bug by fuzzing the Virtual Channels of RDP using WinAFL.

We thought they achieved encouraging results that deserved to be prolonged and improved. The objective was to go even further, by coming up with a general methodology for attacking Virtual Channels in RDP, and fuzz more of Microsoft’s RDP client with WinAFL.

This article aims at retracing my journey and giving out many details, hence why it is quite lengthy.

I will first explain the basics of the Remote Desktop Protocol. Then, I will talk about my setup with WinAFL and fuzzing methodology. Finally, I will present some results I achieved, including bugs and vulnerabilities.

Recent related works

While I was working on this subject, other security researchers have also been looking for vulnerabilities in the RDP client. Some CVEs that came out during this period are CVE-2021-34535, CVE-2021-38631 and CVE-2021-41371.

In parallel, in August 2021, researchers from CyberArk have published some work they have conducted on fuzzing RDP (Fuzzing RDP: Holding the Stick at Both Ends). Even though they also used WinAFL and faced similar challenges, their fuzzing approach is interesting and somewhat differs from the one I will present in this article. They found a few small bugs, including one I found as well (detailled in the RDPSND section).

Why search for vulnerabilities in the RDP client?

In the Blackhat talk, the research was driven by the fact that North Korean hackers would alledgely carry out attacks through RDP servers acting as proxies. By setting up a malicious RDP server to which they would connect, you could hack them back, assuming you found a vulnerability in the RDP client.

Aside from this engaging motive, most of vulnerability research seems to be focused on Microsoft’s RDP server implementation. This is understandable: for instance, a denial of service constitutes a much higher risk for a server than for a client. Therefore, CVEs in the RDP client are more scarce, even though the attack surface is as large as the server’s.

So let’s dive into how RDP works and see for ourselves!

The Remote Desktop Protocol

This article will not explain the Remote Desktop Protocol in depth. If you are interested in that, there are other resources out there that will explain it well, such as articles, or even the official Microsoft specification itself. This article will primarily concentrate on what we need to know in order to fuzz Virtual Channels.

Microsoft has its own implementation of RDP (client and server) built in Windows. There also exist alternate implementations of RDP, like the open-source FreeRDP.

By default, the RDP server listens on TCP port 3389. UDP is also supported to improve performance for certain tasks such as bitmap or audio delivery.

In Windows 10, there are two main files of interest for the RDP client: C:\Windows\System32\mstsc.exe and C:\Windows\System32\mstscax.dll. Reverse engineering will focus on the latter, as it holds most of the RDP logic.

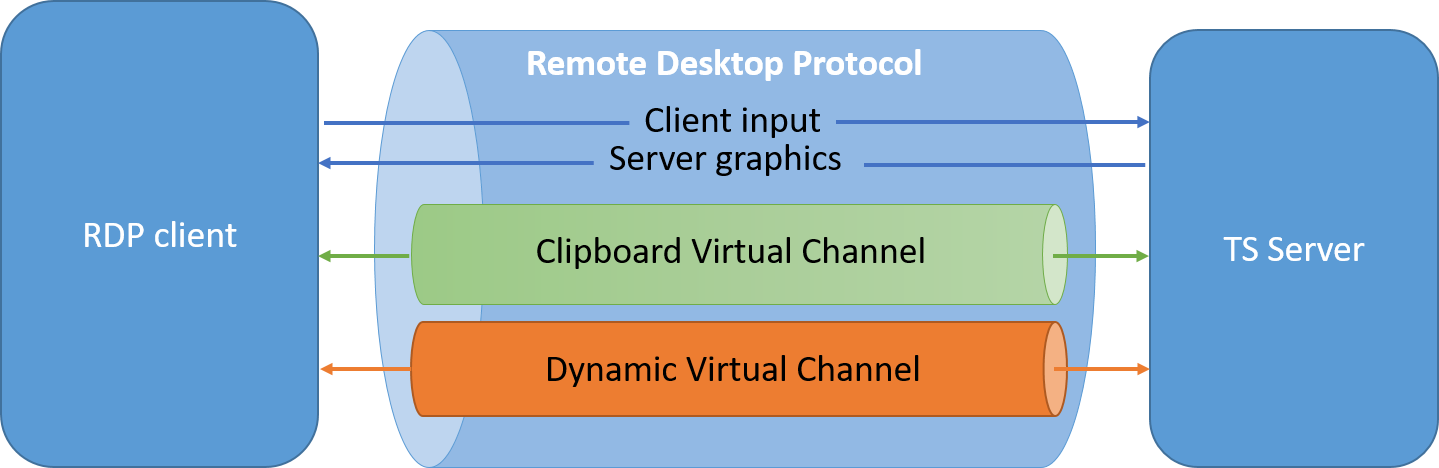

Basic, core functionalities of an RDP client include:

- receiving desktop bitmaps from the server;

- sending keyboard and mouse inputs to the server.

However, a lot of other information can be exchanged between an RDP client and an RDP server: sound, clipboard, support for special types of hardware, etc. This information goes through what Microsoft call Virtual Channels.

Virtual Channels

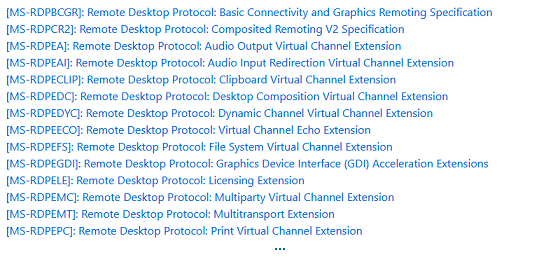

Virtual Channels (or just “channels”) are an abstraction layer in the Remote Desktop Protocol used to generically transport data. They can add functional enhancements to an RDP session. The Remote Desktop Protocol provides multiplexed management of multiple virtual channels.

Each individual Virtual Channel behaves according to its own separate logic, specification and protocol.

Official, documented Virtual Channels by Microsoft come by dozens:

These documentations are an invaluable resource; each channel has its own open specification, and some can span more than a hundred pages.

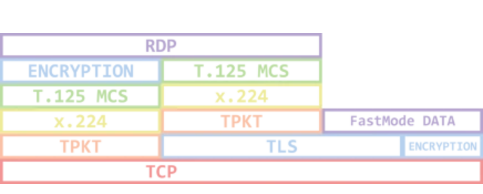

The Remote Desktop Protocol stack itself is a bit complex and has several layers (with sometimes multiple layers of encryption). Virtual Channels operate on the MCS layer.

Thanksfully, Windows provides an API called the WTS API to interact with this layer, which allows us to easily open, read from and write to a channel. This will greatly help us develop a fuzzing harness.

Finally, there are two kinds of Virtual Channels : static ones and dynamic ones.

Static Virtual Channels

Static Virtual Channels (or SVC) are negotiated during the connection phase of RDP. They are opened once for the session and are identified by a name that fits in 8 bytes.

At initialization and by default, the RDP client asks to open the four following SVCs:

RDPSND: audio redirection from the server to the clientCLIPRDR: two-way clipboard redirection/synchronizationRDPDR: filesystem redirection (and more… ;))DRDYNVC: support for dynamic channels

Dynamic Virtual Channels

Dynamic Virtual Channels (or DVC) are built on top of the DRDYNVC Static Virtual Channel, which manages them. In particular, DVCs can be opened and closed on the fly during an RDP session by the server. They are especially used by developers to create extensions, but also by red teamers to exfiltrate data, bypass firewalls, etc.

There are many DVCs. Here are some that are provided by Microsoft:

Microsoft::Windows::RDS::Input(multitouch and pen input)Microsoft::Windows::RDS::Geometry(geometric rendering)Microsoft::Windows::RDS::DisplayControl(display configuration, monitors)Microsoft::Windows::RDS::Telemetry(performance metrics)AUDIO_INPUT(microphones…)RDCamera_Device_Enumerator(webcams…)PNPDR,FileRedirectorChannel(PnP redirection)- …

In conclusion, both types of Virtual Channels are great targets for fuzzing. Each channel behaves independently, has a different protocol parser, different logic, lots of different structures, and can hide many bugs!

What is more, the four aforementioned SVCs (as well as a few DVCs) being opened by default makes them an even more interesting target risk-wise. Indeed, any vulnerability found in these will directly impact most RDP clients.

Fuzzing the RDP client with WinAFL: setup and architecture

As mentioned, we will fuzz our target using WinAFL on Windows. However, WinAFL is not going to work with our target “out of the box”. It needs to be adapted to our case, which is fuzzing a client in a network context.

WinAFL: a brief presentation and choices

WinAFL is a Windows fork of the popular mutational fuzzing tool AFL.

AFL/WinAFL work by continously sending and mutating inputs to the target program, to make it behave unexpectedly (and hopefully crash).

Mutations are repeatedly performed on samples which must initially come from what we call a corpus. A corpus is a set of input files, or seeds, that we need to construct and feed to WinAFL to start. Examples of mutations include bit flipping, performing arithmetic operations and inserting known interesting integers.

In order to achieve coverage-guided fuzzing, WinAFL provides several modes to instrument the target binary:

- Dynamic instrumentation using DynamoRIO

- Hardware tracing using Intel PT

- Static instrumentation with Syzygy

Intel PT has limitations within virtualized environments, and there are too many constraints for us to use Syzygy (compilation restrictions…).

Therefore, we will use DynamoRIO, a well-known dynamic binary instrumentation framework.

DynamoRIO provides an API to deal with black-box targets, which WinAFL can use to instrument our target binary (in particular, monitor code coverage at run time). As a drawback, DynamoRIO will add some overhead, but execution speed will still be decent.

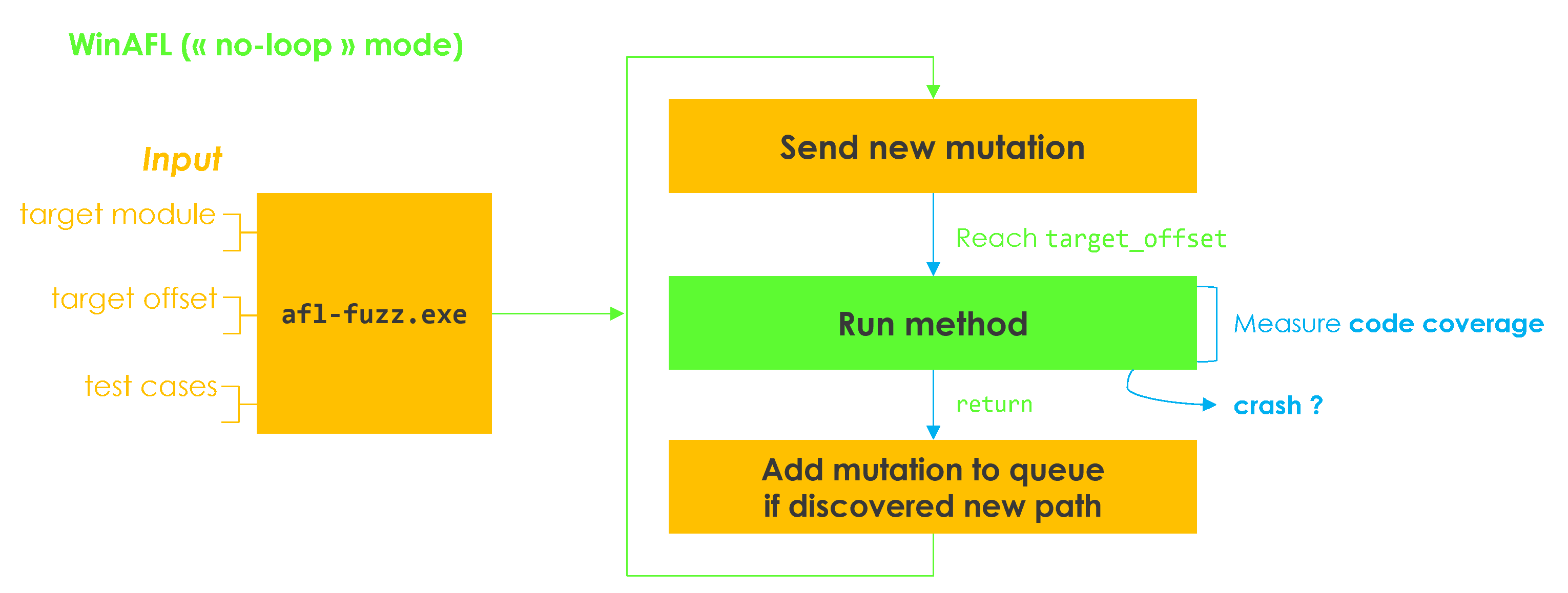

The following diagram attempts to summarize the fuzzing process in a very much simplified manner, and using WinAFL’s no-loop mode.

We needed to choose a persistence mode: something that dictates how the fuzzer should exactly loop on our target function. Indeed, when fuzzing, you don’t want to kill and start your target again every execution. It would be painfully slow, especially with the RDP client, which can sometimes take 10 or 20 seconds to connect.

When using WinAFL with DynamoRIO, there are several persistence modes available for us to choose from:

- Native persistence – measure coverage of the target function, and on

return, reload context and artificially redirect execution back to the start of the target function; - In-app persistence – let the program loop naturally, and coverage will reset each time in the

pre_loop_start_handler, inserted right before the target function.

In-app persistence seems the most adapted to our case. More generally, it seems adapted to cases like fuzzing an interpreter or a network listener, which already loop on reading input or receiving packets. However, it is not ideal because code coverage measurement will not stop at return.

So what is this no-loop mode, you ask me? Well, I’m not sure myself – it is not documented (at least at the time I am writing this article). I just happened to stumble upon it while reading WinAFL’s codebase, and it proves to be totally fit for our network context!

The no-loop mode lets the program loop by its own, just like in-app persistence. But it has the advantage of stopping coverage measurement at return. Funnily enough, the source code of WinAFL itself hints that it is the preferred mode for network fuzzing.

/* We don't need to reload context in case of network-based fuzzing. */

if (options.no_loop)

return;

Last but not least about execution of the RDP client while fuzzing. I did mention the function we target should be fuzzed in a loop without restarting the process. However, it will still restart from time to time: for instance, when reaching the max number of fuzzing iterations (-fuzz_iterations parameter), or simply because of crashes (if we find some).

Since fuzzing campaigns usually last many hours, we can’t be there every time the fuzzer restarts the client to click “Connect” and select a user account. Fuzzing should entirely happen without human intervention.

Therefore, we need the RDP client to be able to connect autonomously to the server. This is easily done with a little trick: use cmdkey to store credentials (cmdkey -generic <ip> -user User -pass 123) and then start the RDP client with mstsc.exe /v <ip>.

Thread coverage within DynamoRIO

Before going any further, I would like to tackle an important concern.

We have just talked about how DynamoRIO monitors code coverage; it starts monitoring it when entering the target function, and stops on return.

There is an important metric in AFL related to coverage: the stability metric.

The stability metric measures the consistency of observed traces. If a program always behaves the same for the same input data, it will earn a score of 100%. […] If it goes into red, you may be in trouble, since AFL will have difficulty discerning between meaningful and “phantom” effects of tweaking the input file.

Most targets will just get a 100% score, but when you see lower figures, there are several things to look at. […]

Multiple threads executing at once in semi-random order: this is harmless when the ‘stability’ metric stays over 90% or so, but can become an issue if not. […]

Indeed, when naively measuring code coverage (the trace) in a multi-threaded application, other threads may interfere with the one of interest.

For this reason, DynamoRIO has a -thread-coverage option. This option allows to collect coverage only from the thread of interest, which is the one that executed the target function.

Forgetting this option while fuzzing the RDP client will inevitably nuke stability, and the fuzzing will likely not be coverage-guided. Instead, it will randomly mutate inputs without knowing which mutations actually yield favorable results (new paths in the correct thread).

Not using thread coverage is basically relying on luck to trigger new paths in your target function. Of course, many crashes can still happen at the first depth level. But in order not to waste fuzzing effort in deeper levels of path geometry while fuzzing a multi-threaded application, one had better use thread coverage within DynamoRIO.

This is a critical fact we must take into account for when we are fuzzing later!

Setting up WinAFL for network fuzzing

By default, WinAFL writes mutations to a file. This file should be passed as an argument to the target binary.

Since we’re fuzzing a network client, we want our harness to act like a server that sends mutations to the client over the network. Thus, the two next steps are:

- Developing a server-side harness

- Adapting WinAFL to a network context

With this in mind, I developed what I will call during the rest of this article the VC Server (for Virtual Channel Server). It is our harness which runs parallel to the RDP server.

Basically, the VC Server will:

- Listen on a TCP port for an input mutation

- Optionally process the mutation

- Send the mutation back to the RDP client through a specified Virtual Channel

This is easily done with the WTS API I mentioned earlier, which allows to open, read from and write to a channel.

For instance, you can open a channel this way:

WTSVirtualChannelOpenEx(WTS_CURRENT_SESSION, "RDPSND", 0);

And you can write to a channel this way:

WTSVirtualChannelWrite(virtual_channel, buffer, length, &bytes_written);

All that remains is to modify WinAFL so that instead of writing mutations to a file, it sends them over TCP to our VC Server. This can be done by patching the function write_to_testcase.

Here’s what our fuzzing « architecture » resembles now.

Other fuzzing preparations

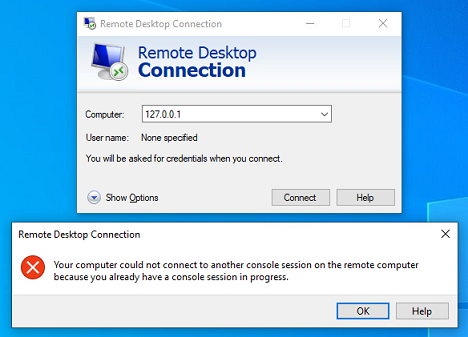

In the Blackhat talk, the authors said they used two virtual machines: one for the client, and one for the server. Do we really need that? Can’t we just connect to a local RDP server on the same machine?

By design, Microsoft RDP prevents a client from connecting from the same machine, both at server level and client level.

To bypass this constraint, there exists a wonderful tool called RDPWrap. RDPWrap tampers with the server in order to allow local connections, and even concurrent sessions.

As for the client application, it seems that only connections to “localhost” and “127.0.0.1” are blocked. You can easily bypass this protection by connecting to “127.0.0.2”, which is equivalent.

A possible setup is thus:

- create two users on the same virtual machine, “User1” and “User2”;

- setup the RDP server with RDPWrap to allow remote connection for User1;

- use the RDP client on a User2 session, by connecting to 127.0.0.2 with the credentials of User1.

Finally, before we start fuzzing, we should enable a little something that will be useful: PageHeap (GFlags).

By activating PageHeap on mstsc.exe with the /full option, we ask Windows to place an inaccessible page at the end of each heap allocation. As soon as something happens out-of-bounds, the client will then crash.

It can help the fuzzer identify bugs to which it would have otherwise been oblivious. For instance, sometimes small out-of-bounds reads will not trigger a crash depending on what’s done with the read value, but can still hide a bigger looming threat.

Fuzzing methodology

We now have a working harness and are pretty much ready to fuzz. But what do we fuzz, and how do we get started?

We did gather earlier a little list of channels that looked like fruitful targets. Especially, the ones that are opened by default and for which there is plenty of documentation.

To illustrate this part, I will use the first channel I decided to attack: the RDPSND channel.

Attacking a channel

Now that we’ve chosen our target, where do we begin? Concretely, we only lack two elements to start fuzzing:

- A target offset

- An initial corpus (seeds)

A good lead is to start by reading Microsoft’s specification (e.g. here for RDPSND). As we said, the specification is a goldmine. It describes the channel’s functioning quite exhaustively, as well as:

- All the message types

- All the data structures

- Protocol diagrams

- Many examples of PDU hexdumps at the end

- Great to seed the fuzzer!

- …

With a good picture of the channel in mind, we can now start reversing the RDP client. We need to locate where incoming PDUs in the channel are handled.

Unfortunately, the way channels globally work in RDP is somewhat circuitous and I never got around to fully figuring it out. Besides, each channel is architectured in a different fashion; there is rarely a common code structure or even naming convention between two channels’ implementation.

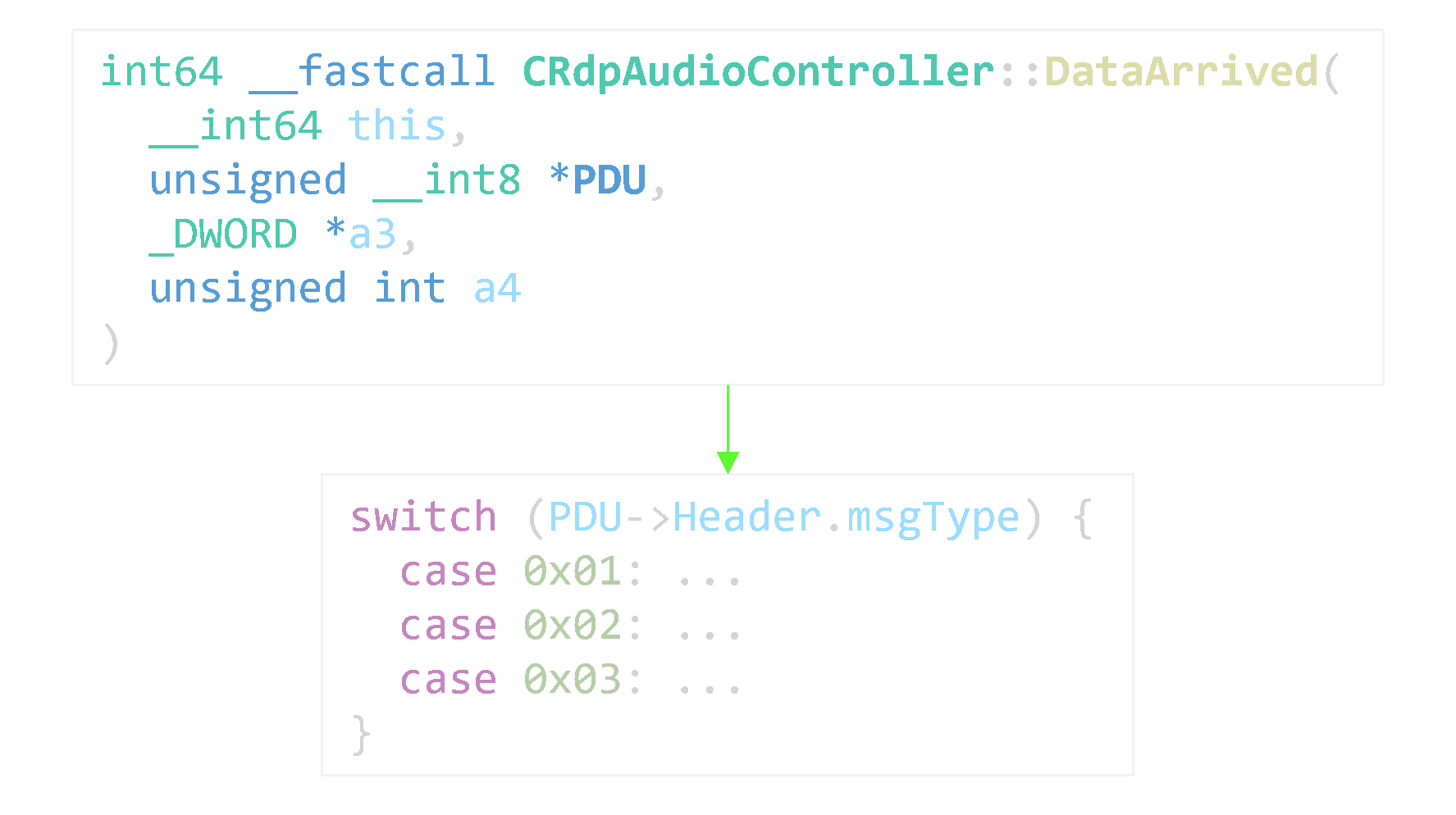

Thanksfully, the PDB symbols are enough to identify most of the channel handlers. Strings or magic numbers from the specification can also help. For RDPSND, our target method’s name is rather straightforward.

If « guessing » won’t work, another possibility is to capture code coverage at the moment we send a PDU over the target virtual channel.

To achieve that, I used frida-drcov.py from Lighthouse. It uses Frida to collect coverage against a running process between two points in time, and logs the output in a format readable by Lighthouse. Lighthouse is an IDA plugin to visualize code coverage.

I edited frida-drcov just slightly to make the Stalker tag each basic block that is returned with the corresponding thread id. This way, I can split the resulting coverage per thread, making it less cluttered.

Fuzzing strategies

We’ve got our target offset: for RDPSND, CRdpAudioController::DataArrived. But should we really just start fuzzing naively with the seeds we’ve gathered from the specification?

We technically have everything we need to start WinAFL. Here’s what a WinAFL command line could look like:

./afl-fuzz.exe -i input -o output -D C:/dynamorio/bin64 -t 30000 -- -target_module mstscax.dll -coverage_module mstscax.dll -target_offset 0x6ADA0 -fuzz_iterations 200000 -no_loop -thread_coverage -- C:/Windows/system32/mstsc.exe -v 127.0.0.2

However, remember we’re fuzzing in a network context. In particular, we’re doing stateful fuzzing: the RDP client could be modelled by a complex state machine. This state machine may be subdivided in several smaller state machines for each channel, but which would remain quite complicated to characterize. This implies a lot; we will talk about this.

I came up with basically two different strategies for fuzzing a channel that I will detail: mixed message type fuzzing and fixed message type fuzzing.

Mixed message type fuzzing

This strategy is what you’d get by fuzzing the channel « naively ». This means, fuzzing with the raw seeds from the specification and without modifying the harness any further. In this case, the harness just sends back the mutation it receives as it is (apart from some exceptions such as overwriting a length field, which we will talk about later).

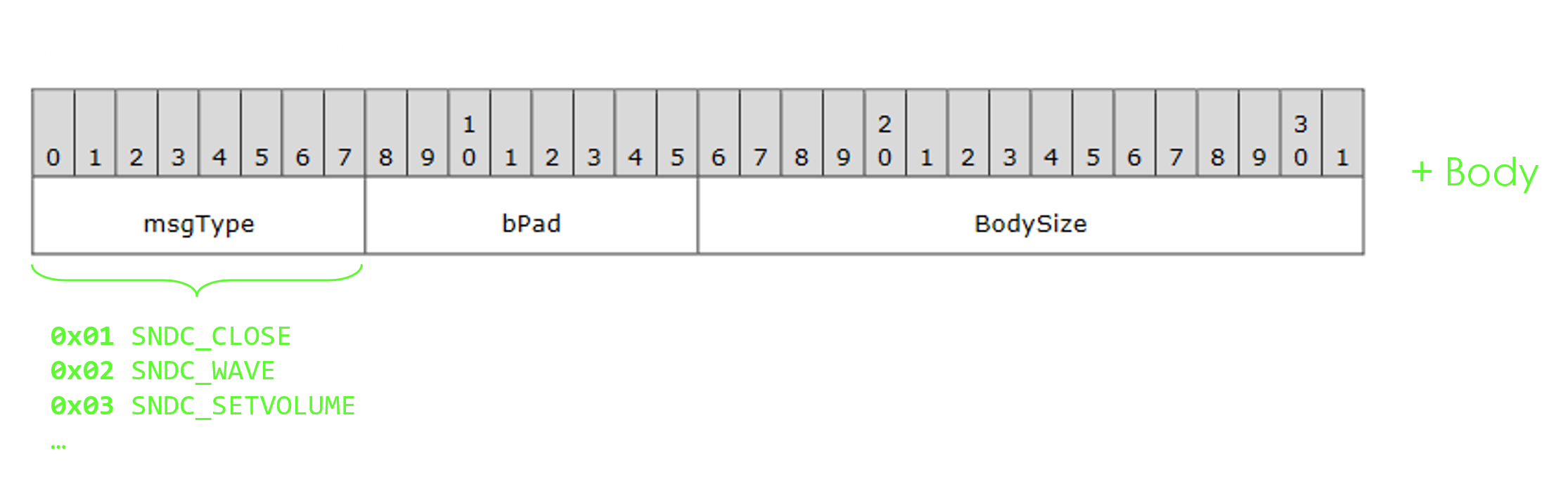

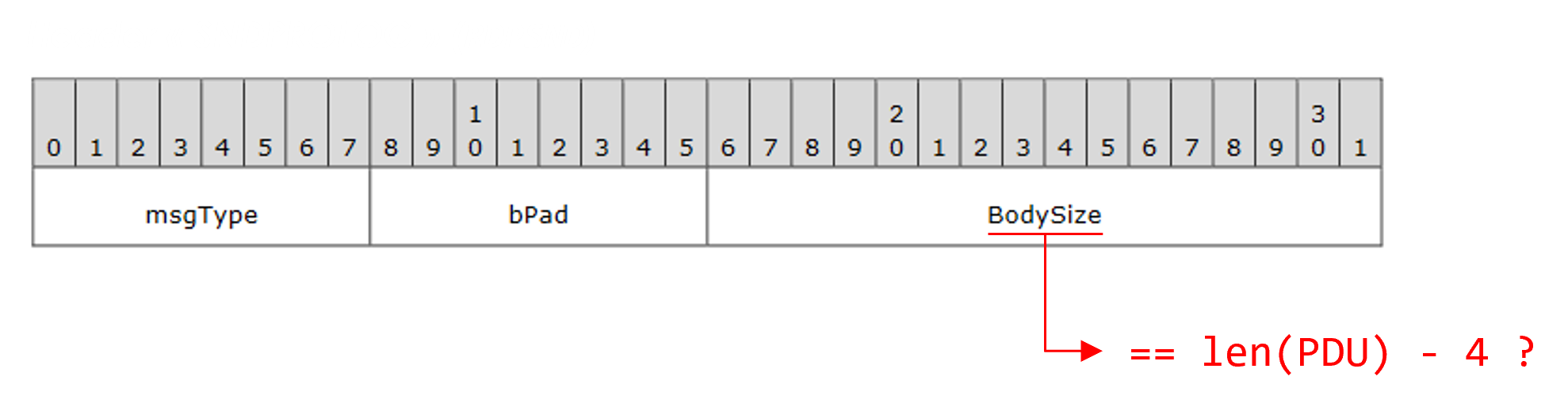

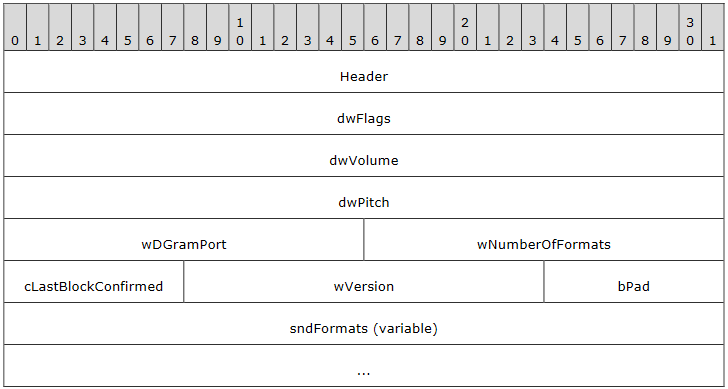

Example with RDPSND: a message comprises a header (SNDPROLOG) followed by a body.

Since the seeds include the header, the fuzzer will also mutate it, including the msgType field. Therefore, the RDP client will receive a lot of different message types, in a rather random order.

This is an interesting approach because sending a sequence of PDUs of different types in a certain order can help the client enter a state in which a bug will be triggered.

A drawback of this strategy is that crash analysis becomes more difficult. Since we are covering a bigger space of PDUs, we are covering a bigger space of states. In this case, there may be a higher chance that the crash we found originates from a “stateful bug”, and which statefulness can be increasingly complex.

In layman’s terms: imagine WinAFL finds a crash and saves the corresponding mutation. There is no guarantee whatsoever you will be able to reproduce the crash with this mutation only.

If you try to reproduce the crash and it doesn’t work, it’s probably because it’s actually rather a sequence of PDUs that made the client crash, and not just a single PDU. However, understanding which sequence of PDUs made the client crash is hard, not to say often a lost cause.

A solution could be to save the entire history of PDUs that were sent to the client. By replaying the whole history, you may hope the client behaves in a deterministic enough way that it reproduces the crash.

But fuzzing the RDP client, I often got speeds between 50 and 1000 execs/s. In the “pessimistic” case in which we’re fuzzing at high speeds for a whole week-end and mutations are 100 bytes long on average, that’s 24 GB of PDU history. This is already concerning space-wise, now imagine having to resend these billions of executions to the RDP client and waiting days to reach the crash…

Fixed message type fuzzing

This time, we want to let WinAFL fuzz only the body part of the message. In particular, the msgType field will be fixed, so we need to start a fuzzing campaign for each message type (there are 13 in RDPSND).

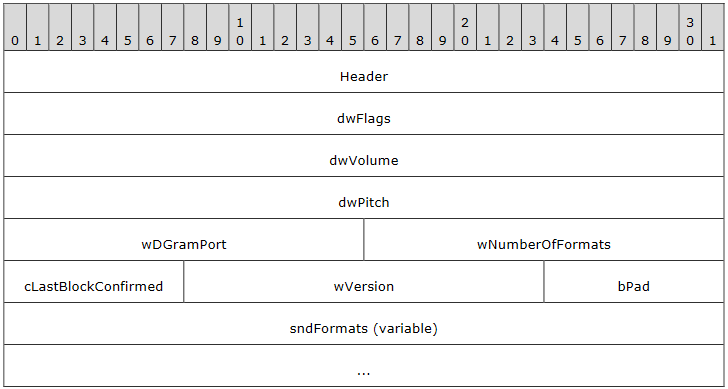

For example, we could say we’re specifically targeting Server Audio Formats and Version PDUs in RDPSND (SERVER_AUDIO_VERSION_AND_FORMATS, msgType 0x07). In this case, we are only fuzzing what’s below Header in the following diagram.

This strategy is still vulnerable to the presence of stateful bugs, but less than in mixed message type fuzzing, because the state space is usually smaller.

However, it requires some more preparation:

- « Beheading » the seeds (the fuzzer only needs to mutate on the bodies).

- Writing a channel-specific wrapper in the VC Server to reconstruct and add the header before sending the PDU to the client.

- Identifying handlers for each message type.

- Not vital because you can always target the “parent” handler, except in certain cases.

- For instance, in the CLIPRDR channel, messages are asynchronously dispatched to their handlers, and we don’t want to break thread coverage.

In conclusion, it’s nice to try both fuzzing approaches for a channel. The first one can find interesting bugs, but which sometimes are very hard to analyze. The second one needs a bit more effort to setup, but allows to go more in depth in each message type’s logic. Even though it finds fewer bugs, they’re usually easier to reproduce.

Leveraging the harness

Our harness, the VC Server, can do much more than just “echo” mutations.

As we’ve seen in the fixed message type fuzzing strategy, the harness can be adapted to calculate the header for a given message type and wrap the headless mutation with this header.

The harness is also essential to avoid edge cases.

These can happen in parsing logic: in RDPSND (and similarly in many other channels), the Header includes a BodySize field which must be equal to the length of the actual PDU body. If it’s not, nothing happens — the message is simply ignored.

It is too easy for the fuzzer to mutate the BodySize field and break it, in which case most of the mutations go to waste.

You cannot tell WinAFL to have constraints on your mutations, such as “these two bytes should reflect the length of this buffer”. AFL’s mutational engine is not intended to work this way.

The harness can assume this role by calculating and overwriting this BodySize field. Of course, this is specific to RDPSND and such patches should happen in each channel.

Another obvious type of edge case is… crashes. If we find a crash, there’s a high chance there are actually a lot of mutations that can trigger the same crash. You’ll get tons of the same crashes in a row, which can heavily slow down fuzzing for certain periods of time. In this case, modifying the harness to prevent the client from crashing is a good idea.

Analyzing crashes

As mentioned, analyzing a crash can range from easy to nearly impossible.

When WinAFL finds a crash, the only thing it pretty much does is save the mutation in the crashes/ folder, under a name such as id_000000_00_EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION.

From there, there are two possibilities:

- You are able to reproduce the crash manually. In this case, just reverse to understand the root cause, analyze risk, and maybe grow the crash into a bigger vulnerability.

- You are not able to reproduce the crash manually. In this case: lie down, try not to cry, cry a lot.

On a more serious note, if you can’t reproduce the crash:

- Dissect the guilty payload. Perhaps understanding the PDU will directly point towards a bug.

- For instance, if you notice the message type has a field which is an array of dynamic length, and that this length is coded inside another field and does not seem to match the actual number of elements in the array, maybe it’s an out-of-bounds bug about improper length checking.

- If dissecting the payload does not yield anything, maybe it’s a “stateful bug” and you’re doomed.

Too often I found crashes that I couldn’t reproduce and had no idea how to analyze. To try and mitigate this a bit, I modified WinAFL to incorporate a feature that proved to be rather vital during my research: logging more information about crashes.

More specifically, everytime a crash is encountered, WinAFL/DynamoRIO will now log the exception address, module and offset, timestamp, and also exception information (like if there’s an access violation on read, which address was tried to be read).

if ((exception_code == EXCEPTION_ACCESS_VIOLATION) ||

(exception_code == EXCEPTION_ILLEGAL_INSTRUCTION) ||

(exception_code == EXCEPTION_PRIV_INSTRUCTION) ||

(exception_code == EXCEPTION_INT_DIVIDE_BY_ZERO) ||

(exception_code == STATUS_HEAP_CORRUPTION) ||

(exception_code == EXCEPTION_STACK_OVERFLOW) ||

(exception_code == STATUS_STACK_BUFFER_OVERRUN) ||

(exception_code == STATUS_FATAL_APP_EXIT)) {

if(options.debug_mode) {

dr_fprintf(winafl_data.log, "crashed\n");

} else {

mod_entry = module_table_lookup(winafl_data.cache, NUM_THREAD_MODULE_CACHE, module_table, (app_pc)excpt->record->ExceptionAddress);

file_t crash_log = dr_open_file("crash.log", DR_FILE_WRITE_APPEND);

time_t ltime;

time(<ime);

dr_fprintf(crash_log, "Crash at time %li\n", ltime);

if (mod_entry == NULL || mod_entry->data == NULL) {

dr_fprintf(

crash_log,

"Exception Address: %016llx / %016llx (unknown module)\n",

((unsigned __int64) excpt->record->ExceptionAddress),

((unsigned __int64) excpt->record->ExceptionAddress) - module_start

);

} else {

dr_fprintf(

crash_log,

"Exception Address: %016llx / %016llx (%s)\n",

((unsigned __int64) excpt->record->ExceptionAddress),

((unsigned __int64) excpt->record->ExceptionAddress) - (unsigned __int64)mod_entry->data->start,

dr_module_preferred_name(mod_entry->data)

);

}

dr_fprintf(crash_log, "Exception Information: %016llx %016llx\n", excpt->record->ExceptionInformation[0], excpt->record->ExceptionInformation[1]);

dr_fprintf(crash_log, "\n");

dr_close_file(crash_log);

WriteCommandToPipe('C');

WriteDWORDCommandToPipe(exception_code);

}

dr_exit_process(1);

}

This allows to know precisely in which function and which instruction a crash happened. Usually it’s in mstscax.dll, but it could also happen in another module. It is worth noting a crash in an “unknown module” could mean the execution flow was redirected, which accounts for the most interesting bugs… :)

Sadly, we can’t do much more. Something very valuable would be having a call stack dump on crashes. However, DynamoRIO does not have such a feature, and we can’t do it through procdump or MiniDumpWriteDump either because the client is already a debuggee of DynamoRIO (drrun).

Having the module and offset is already of a huge help in understanding crashes though: start reversing the client where it crashed and work your way backwards.

Assessing fuzzing quality

Let’s say we fuzzed a channel for a whole week-end. Everything works, everything is sunshine and rainbows, maybe we’ve even been lucky enough to find bugs.

When do we stop exactly? We’re not gonna fuzz this channel forever, we’ve still got many other places to fuzz.

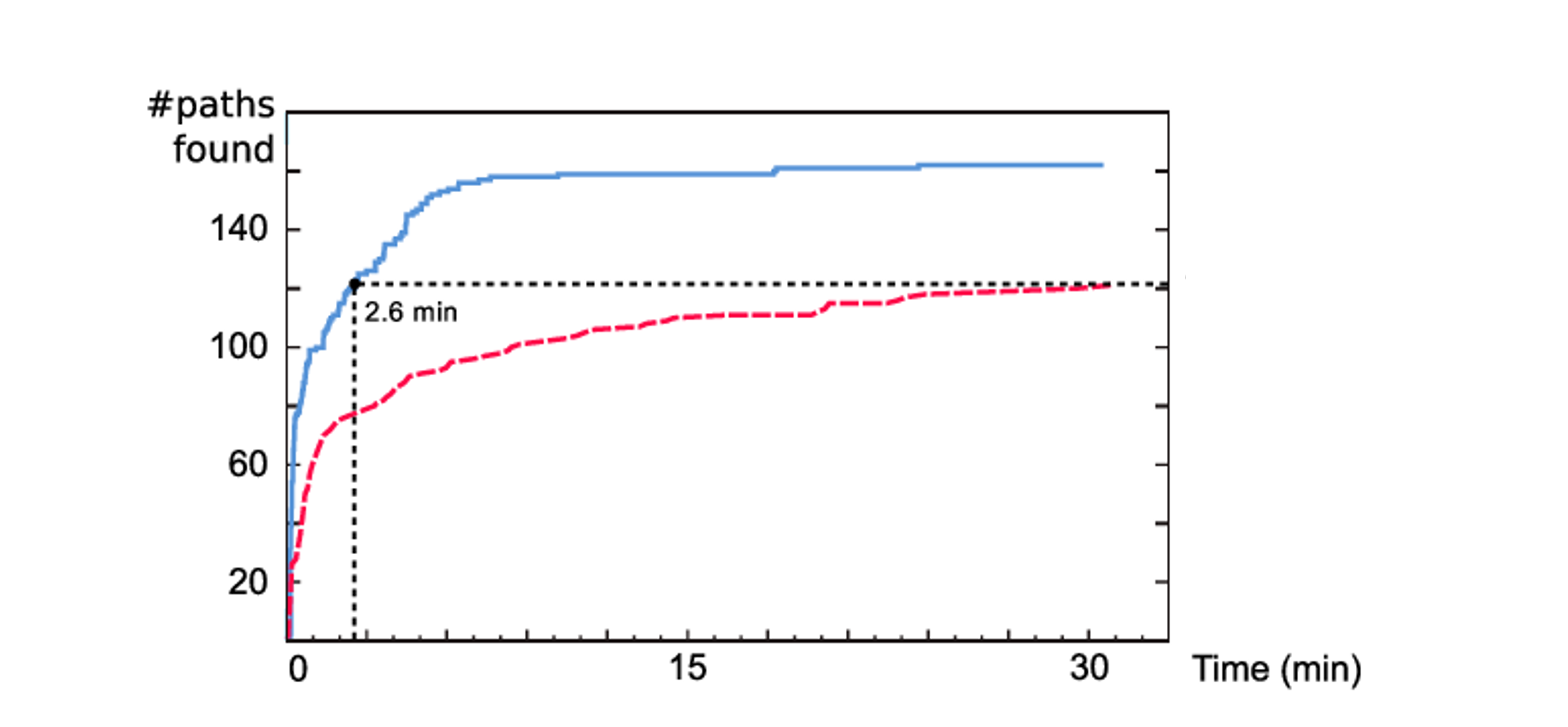

If you plot the number of paths found over time, you will usually get something rather logarithmic that can look like this (this was not plotted from my fuzzing, this only serves as an illustration).

Fuzzing is gambling. Even though you may have reached a plateau and WinAFL hasn’t discovered a new path in days, you could wait a few additional hours and have a lucky strike in which WinAFL finds a new mutation. This new mutation could snowball into dozens of new paths, including a crash that leads to the next big RCE.

The key question is: are we satisfied with our fuzzing?

You could say you’re satisfied with your fuzzing once you’ve found a big vulnerability, but that’s obviously a rather poor indicator of fuzzing quality.

Instead, it is preferable to assess fuzzing quality by looking at coverage quality. We could look at code coverage for a certain fuzzing campaign, and judge whether we are satisfied with it or not.

In order to do that, I modified WinAFL to add a new option: -log_signal. WinAFL will save all the basic blocks encountered at each fuzzing iteration in a temporary buffer (in the thread of interest). Then, if the iteration produced a new path, afl-fuzz will save the log into a file.

Therefore, for each new path, we have a corresponding basic block trace log. We can convert such a log into the Mod+Offset format that Lighthouse can read to visualize code coverage.

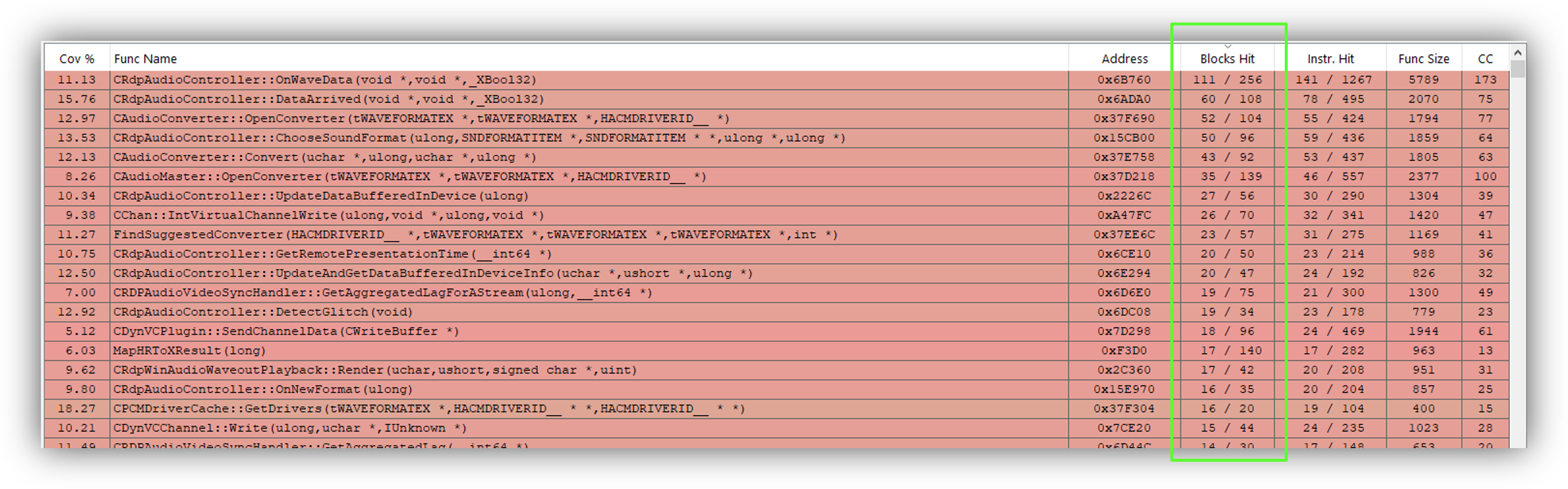

For RDPSND, we can get something like this.

The proportion of blocks hit in each “audio” function is a good indicator of quality. Though here, it is rarely >50% because there is a large proportion of error-handling blocks that are never triggered. Hence why all the functions are colored in red, but it is not very important.

Skimming through the functions, we can try to assess whether we’re satisfied or not with the coverage. Although, this requires having reversed engineered the channel enough to have a good depiction of what’s going on in mind — more specifically, knowing what are all the functions and basic blocks we are interested in.

Results

In this section, I will present some of my results in a few channels that I tried to fuzz.

| Channel | Description | Fuzzing level | Bugs found |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDPSND | Audio redirection | 2 | 1 |

| CLIPRDR | Clipboard | 1 | 1 |

| DRDYNVC | Dynamic channels support | 0 | |

| RDPDR | Filesystem redirection, printers, smart cards… | 2 | 3 |

Fuzzing level is a subjective scale to assess how much I fuzzed each channel:

- 0 = Could not fuzz

- 1 = Could fuzz more or better

- 2 = Quite satisfied with my fuzzing campaigns (but there might be more to fuzz…)

RDPSND

RDPSND is a static virtual channel that transports audio data from server to client, so that the client can play sound originating from the server. It is opened by default.

I fuzzed most of the message types referenced in the specification. Each message type was fuzzed for hours and the channel as a whole for days. Fuzzing coverage is decent.

I found one bug that crashed the client: an Out-of-Bounds Read that is unfortunately unexploitable. The crash itself is not especially interesting, but I will still detail it because it’s a great example of stateful bug.

Out-of-Bounds Read in RDPSND

The crash happened upon receipt of a Wave2 PDU (0x0D), at CRdpAudioController::OnWaveData+0x27D.

Let’s dissect the PDU:

0d 00 10 00 // Header

16 a1 // wTimeStamp

0f 00 // wFormatNo

20 // cBlockNo

f5 00 00 // bPad

c2 b8 b3 0d // dwAudioTimeStamp

de 20 be ef // Data

Nothing particularly shocking right away. On a purely semantic level, fields that could be good candidates for a crash are wFormatNo or cBlockNo, because they could be used for indexing an array.

Reversing the OnWaveData function will surely make things clearer. Here’s the interesting piece:

wFormatNo = PDU->Body.wFormatNo;

// Has wFormatNo changed since the last Wave PDU?

if (wFormatNo != this->lastFormatNo) {

// Load the new format

if (!CRdpAudioController::OnNewFormat(this, wFormatNo)) {

// Error, exit

}

this->lastFormatNo = wFormatNo;

}

// Fetch the audio format of index wFormatNo

savedAudioFormats = this->savedAudioFormats;

targetFormat = *(AudioFormat **)(savedAudioFormats + 8 * wFormatNo);

wFormatTag = targetFormat->wFormatTag;

if (wFormatTag == 1) {

// ...

}

The out-of-bounds read is quite evident: we control wFormatNo (unsigned short). However, manually sending the malicious PDU again does not do anything – we are unable to reproduce the bug.

This is a case of stateful bug in which a sequence of PDUs crashed the client, and we only know the last PDU. We’re gonna have to manually reconstruct the puzzle pieces!

Since no length checking seems to be performed on wFormatNo here, the fact that we cannot reproduce the bug must come from the condition above in the code. Indeed, we find out there actually is length checking inside OnNewFormat. We need to find a way to skip this condition to trigger the bug.

In order to skip the condition, we need to send a format number that is equal to the last one we sent. But to trigger a bug, we want the format number to be bigger than the number of formats; how do we achieve that by not changing the format number?

The answer lies in the Server Audio Formats and Version PDU.

This PDU is used by the server to send a list of supported audio formats to the client. The client will save this list of formats in this->savedAudioFormats. So we can simply send a Format PDU between two Wave PDUs to make the list smaller. Here’s the idea:

- Send ∳n > 1∳ formats to the client through a Format PDU.

- Send a Wave PDU with

wFormatNoset to ∳n∳. - Send a new Format PDU with ∳k < n∳ formats: the format list is freed and reconstructed.

- Send the same Wave PDU than in step 2: since

lastFormatNois ∳n∳, we bypass length-checking insideOnNewFormatand trigger the out-of-bounds read.

Now, we can’t do much with this primitive: we can probably read arbitrary memory, but wFormatTag is only used in a weak comparison (wFormatTag == 1). We can’t leak much information remotely.

All in all, this bug is still interesting because it highlights how mixed message type fuzzing can help find new bugs. WinAFL managed to find a sequence of PDUs which bypasses a certain condition to trigger a crash — and we could have very well overlooked it if we were manually searching for a vulnerability.

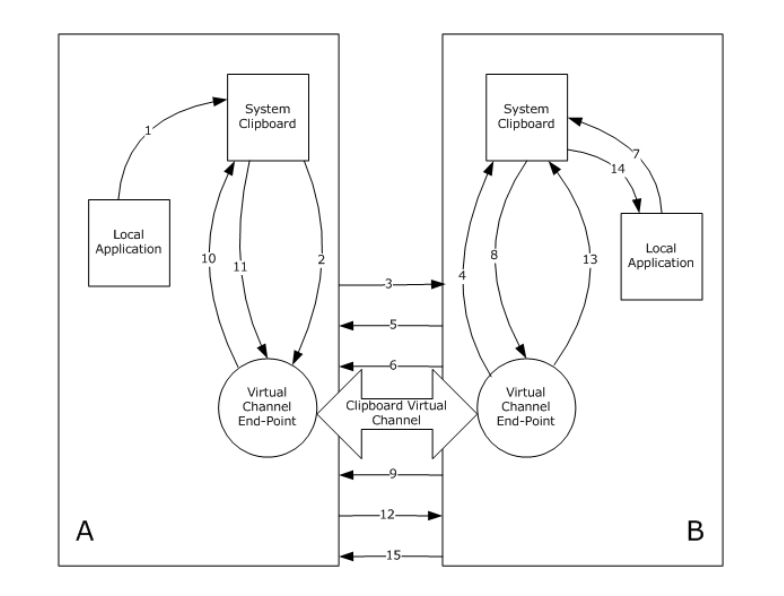

CLIPRDR

CLIPRDR is a static virtual channel dedicated to synchronization of the clipboard between the server and the client. It allows to copy several types of data (text, image, files…) from server to client and from client to server. It is opened by default.

There’s a twist with this channel: it’s a state machine. By that, I mean that unlike the other channels, it’s a real state machine with proper state verification, and it is even documented.

Indeed, each PDU sub-handler (logic for a certain message type) calls the CheckClipboardStateTable function prior to anything else. This function tracks and ensures the client is in the correct state to process the PDU. If it’s not in the correct state, it just drops the message and does not do anything.

This is a problem for two major reasons:

- If we are performing mixed message type fuzzing, a lot of our fuzzing effort will go to waste. Few PDU sequences will actually make sense and bring the client to the right state at the right time.

- We can’t perform fixed message type fuzzing, unless for each message type we find a way to force the client to be in the right state. This is a lot of effort to characterize and implement.

There’s a second twist with this channel: incoming PDUs are dispatched asynchronously.

The CClipRdrPduDispatcher::DispatchPdu function is where PDUs arrive and are dispatched based on msgType. It contains many dynamic calls that all lead to CTSCoreEventSource::FireASyncNotification. The PDU sub-handling logic is therefore run in a different thread.

This means we can’t use the -thread_coverage option anymore if we target DispatchPdu… So we can’t perform mixed message type fuzzing with reliable coverage anymore. On the other hand, as we said, we can’t perform fixed message type fuzzing either at all because of state verification.

Therefore, we don’t have much choice but to perform blind mixed message type fuzzing (without thread coverage).

I was still able to identify a little bug with this fuzzing strategy.

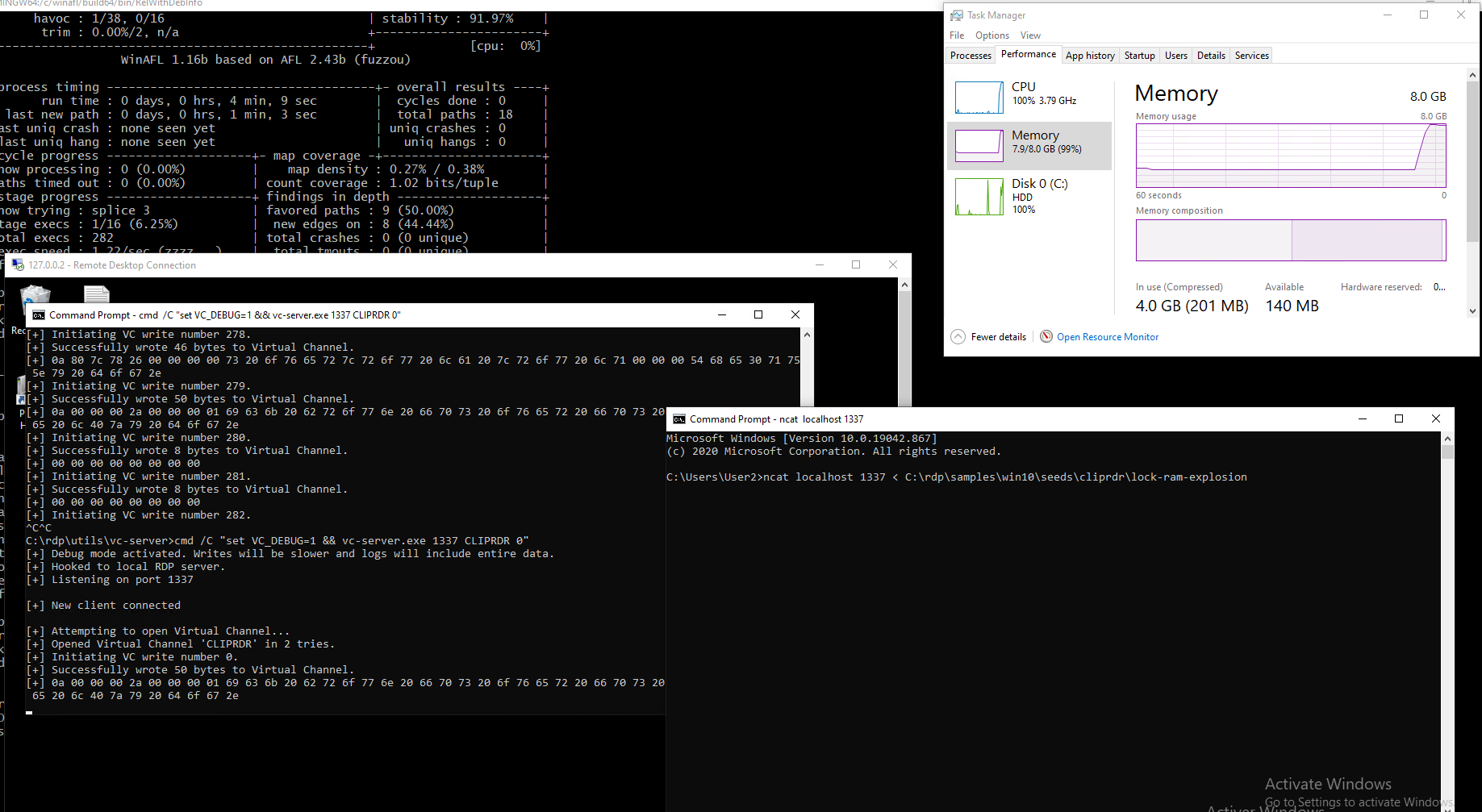

Arbitrary Malloc DoS in CLIPRDR

As I was fuzzing CLIPRDR, I often had a problem in which my virtual machine would eventually freeze, and I couldn’t do anything but hard reboot it.

The thing is, I spent an unreasonable amount of time thinking: “this problem sucks, I can’t go any further because of it, my setup is broken, I don’t know why, and I am doomed because I cannot fuzz anymore”.

I kept blaming myself because the fuzzing setup is complex, unstable, and this was not the first time I was encoutering weird bugs. Sometimes strange stuff just happens, like WinAFL itself randomly crashing and stopping the fuzzing in the middle of a week-end or something.

Whereas what I should have been thinking all this time is: “something is broken, and that’s good because that’s what I’m aiming for. If something behaves strangely, then I need to find the reason why. Maybe this will lead me to new findings, and even a reproducible bug.”

I feel like attitude plays a great role in fuzzing. Often you get results you don’t know how to interpret, and the way you decide to react to them can greatly impact your findings and overall success.

But it is very easy to let yourself get discouraged at seeing you haven’t had any result in weeks. It’s easy to lack motivation to have the right attitude at the right time towards a certain type of result, and actually getting stuff done (investigating, confirming/rejecting hypotheses, etc.).

Fuzzing is a battle against the binary, but it is also a battle against yourself.

The freezing always happened at a random time since I was fuzzing in non-deterministic mode. I eventually switched to deterministic and noticed it usually happened around 5 minutes of fuzzing.

I modified my VC Server to integrate a slow mode. This way, I could have time to monitor which PDU was guilty and what exactly happened when it was sent.

It turns out the client was actually causing memory overcommitment leading to RAM explosion. The virtual machine’s RAM would very quickly fill up, until at some point having to start filling up swap. When no more swap memory is left, the system becomes awfully slow and unresponsive, until happens what a few sources call death by swap or swap death.

I was able to isolate the malicious PDU and reproduce the bug with a minimal case:

0A 00 // msgType

00 00 // msgFlags

04 00 00 00 // dataLen

01 69 63 6B // clipDataId

It is a Lock Clipboard Data PDU (0x000A), which basically only contains a clipDataId field. In the function CClipBase::OnLockClipData, this field is used with some kind of “smart array” object:

EnterCriticalSection(...);

v5 = SmartArray<CFileContentsReaderManager>::AddAt(

this,

PDU->clipDataId,

v9

) == 0 ? 0x8007000E : 0;

LeaveCriticalSection(...);

Eventually, the function DynArray<SmartArray<RdpStagingSurface,unsigned long>::CCleanType,unsigned long>::Grow is called and performs:

v5 = operator new(saturated_mul(32 + clipDataId, 8ui64));

My guess is that an array of dynamic length is used to store information, such as a lock tag, about file streams based on their id (if this is really the case, then it is probably poor choice of data structure). If the array is not big enough when trying to access a certain index, then it is reallocated with sufficient size.

This leads to a malloc of size ∳8 \times (32 + \text{clipDataId})∳, which means at maximum a little more than 32 GB. Of course, on systems with a moderate amount of RAM like an employee’s laptop, this may be dangerous.

Risk-wise, this is a case of remote system-wide denial of service. Obviously, it’s less impressive on a client than on a server, but it’s still nastier than your usual mere crash.

Microsoft acknowledged the bug, but unsurprisingly closed the case as a low severity DOS vulnerability. I still think it could have deserved a little fix. Imagine a Windows machine that hosts several critical services, and from which you can connect to another machine through RDP — since the DOS hangs the entire system, these critical services would be impacted too.

While writing a PoC, I noticed something interesting. Depending on how much available RAM there is left on the client, you cannot just send a PDU with 0xFFFFFFFF as clipDataId. The client will try to allocate too much at once, and malloc will return ERROR_NOT_ENOUGH_MEMORY. But you still need to make the client allocate enough memory to reach death by swap. Thus, my exploit sends the malicious payloads with smaller 128 MB increments to adapt to the amount of RAM on the victim’s system.

char payload[] = {

0x0A, 0x00, // msgType

0x00, 0x00, // msgFlags

0x04, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // dataLen

0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF, 0x00 // clipDataId

};

connect_to_virtual_channel("cliprdr", 10, STATIC_CHANNEL);

for (int c = 0; c < 256; c++) {

payload[11] = (char)c; // Allocate memory with 128MB increments

write_to_virtual_channel(payload, sizeof(payload));

Sleep(100);

}

close_virtual_channel();

From this bug, we learned a golden rule of fuzzing: that it is not only about crashes.

Side effects of fuzzing on a system can reveal bugs too.

DRDYNVC

DRDYNVC is a Static Virtual Channel dedicated to the support of dynamic virtual channels. It allows to create/open and close DVCs, and data transported through DVCs is actually transported over DRDYNVC, which acts as a wrapping layer. It is opened by default.

When I got started on this channel, I began studying the specification, message types, reversing the client, identifying all the relevant functions… Until realizing a major issue: I was unable to open the channel through the WTS API (ERROR_ACCESS_DENIED).

I thought it could be an issue with WTSVirtualChannelOpen specifically, so I tried with its counterpart WTSVirtualChannelOpenEx. No luck.

I spent a lot of time on this issue because I had no idea where the opening could fail. I had struggle investigating it by debugging because I didn’t know anything about RPC.

Indeed, WTSAPI32 eventually ends up in RPCRT4.DLL, responsible for Remote Procedure Calls in Windows.

I tried logging debug strings from winsta!WinStationVirtualOpenEx with DebugView++. This requires patching winsta.dll to activate g_bDebugSpew:

WINSTA: ERR::RpcCreateVirtualChannel failed: 0x80070005 in CreateVirtualChannel

With some help, we eventually managed to identify the endpoint of the RPC call, in termsrv.dll. There are two functions of interest:

CRCMPublicRpc::Start, which starts listening for RPC calls and sets up ACL;RpcCreateVirtualChannel, which handles the call.

The issue must come either from ACL, or from the handling logic. ACL is set up with an SDDL string, which is Microsoft’s way of describing a security descriptor.

D:(A;;GRGWGX;;;WD)(A;;GRGWGX;;;RC)(A;;GA;;;BA)(A;;GA;;;OW)(A;;GRGWGX;;;AC)(A;;GRGWGX;;;S-1-15-3-1024-1864111754-776273317-3666925027-2523908081-3792458206-3582472437-4114419977-1582884857)

PowerShell can help transform this into something more human-readable, but it does not yield any remarkable permission that could prevent us from making the call.

The issue then probably comes, as hinted by the debug spew, from RpcCreateVirtualChannel.

I debugged the TermService svchost process and stepped until ending up inside rdpcorets.dll. The function CUMRDPConnection::CreateVirtualChannel answers our inquiry.

if ( !_stricmp("DRDYNVC", a2)

|| !_stricmp("rdpgrfx", a2)

|| !_stricmp("rdpinpt", a2)

|| !_stricmp("rdpcmd", a2)

|| !_stricmp("rdplic", a2)

|| !_stricmp("Microsoft::Windows::RDS::Graphics", a2) )

{

v16 = 0x80070005;

goto LABEL_58;

}

DRDYNVC is really banned from being opened through the WTS API…!

We also notice a few more channels that are blacklisted the same way. I tried patching rdpcorets.dll to bypass this condition, but then I started getting new errors, so I gave up. Perhaps this channel is really meant not to be opened with the WTS API…

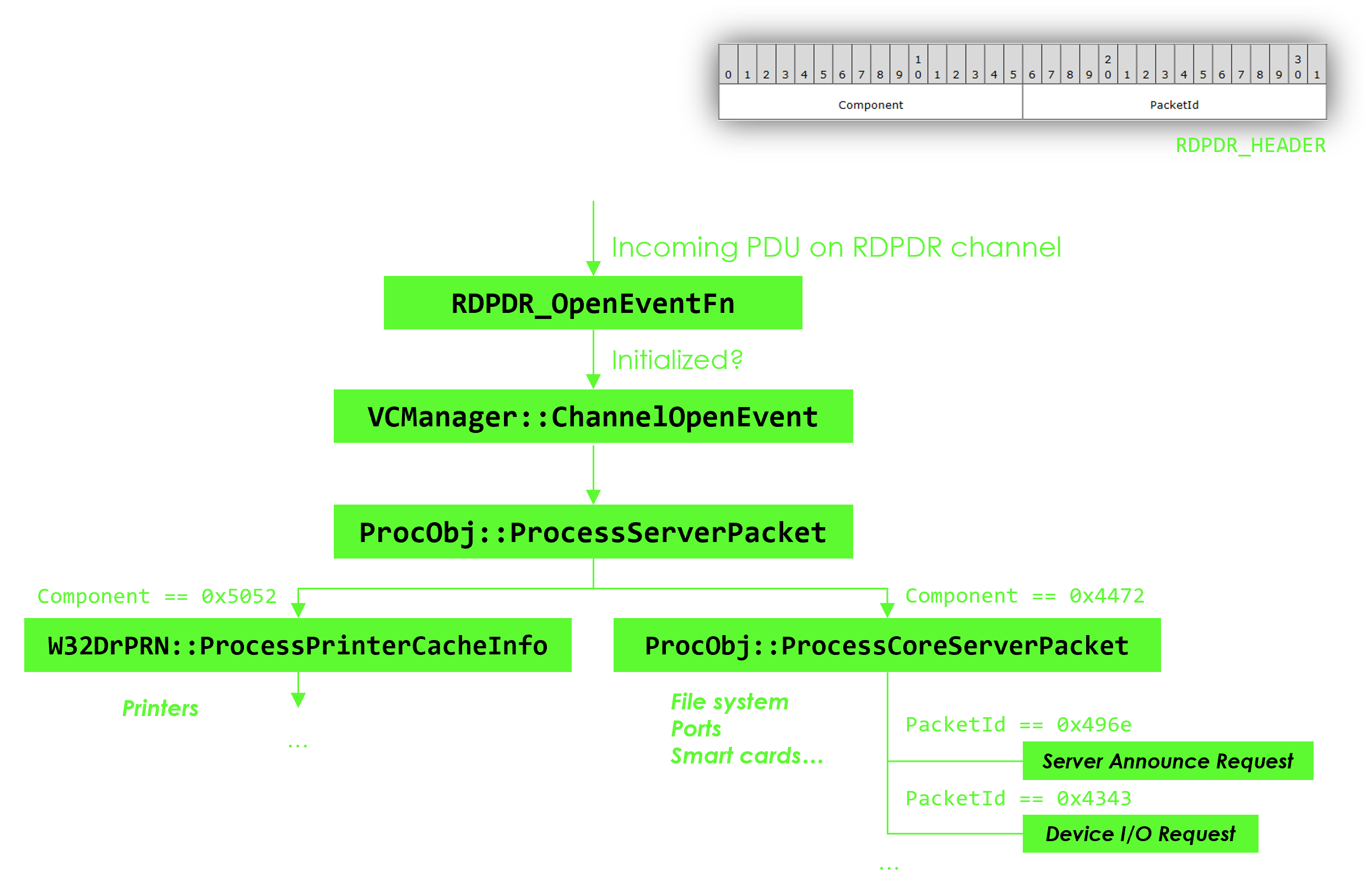

RDPDR

RDPDR is a Static Virtual Channel dedicated to redirecting access from the server to the client file system. It is opened by default. It is also the base channel that hosts several sub-extensions such as the smart card extension, the printing extension or the ports extension. Finally, it is probably the most complex and interesting channel I’ve had to fuzz among the few ones I’ve studied!

Here’s what the architecture of the channel’s client implementation resembles:

When I tried to start fuzzing RDPDR, there was a little hardship. After around a hundred iterations, the fuzzing would become very slow. The reason was that the client closes the channel as soon as the smallest thing goes wrong while handling an incoming PDU (length checking failure, unrecognized enum value…). Once the channel is closed, we can’t send PDUs anymore.

More specifically, the client calls VCManager::ChannelClose which calls VirtualChannelCloseEx. This is funny because this function sounds like it’s from the WTS API, but it’s not. It looks more like legacy. We can find a description of this function in an older RDP reference page:

This function closes the client end of a virtual channel. This function is a virtual extension that can be used to protect per-session data in the virtual channel client DLL.

So it seems that it is indeed used, rightfully, for security purposes. This means we probably won’t be able to find a lot of stateful bugs, if a PDU in a sequence triggers the channel closing. However, bugs can still happen before channel is closed, and some bugs may even not trigger it.

I patched mstscax.dll to get rid of this measure, by nopping out the dynamic call to VirtualChannelCloseEx and bypassing the error handler. We have to be extra careful with patches though, because they can modify the client’s behavior. As a result, real bugs in the RDP client will only constitute a subset of the bugs we will find with the patched DLL.

With this new gear, I fuzzed the whole channel, including, how Microsoft calls them, its sub-protocols (Printer, Smart Cards…). I eventually identified three bugs.

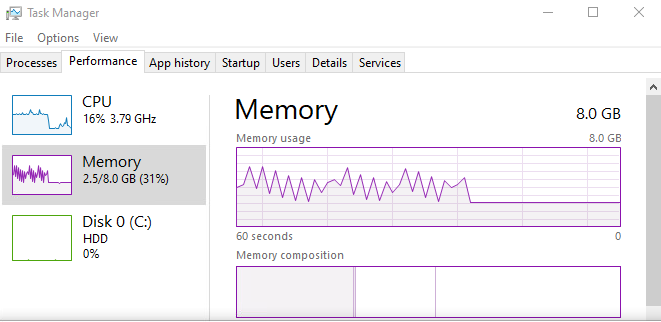

Arbitrary Malloc DoS in RDPDR

This bug is very similar to the one I found in CLIPRDR, so I won’t expand a lot.

It was found within a few minutes of fuzzing. At first, my virtual machine had only 4 GB of RAM, so death by swap (which we know of and are used to by now) would happen. Upgrading to 8 GB of RAM solved the issue, meaning the memory overcommitment was not as violent as in the CLIPRDR bug. Fuzzing with 8 GB RAM showed funny things:

Here’s what the guilty PDU looks like:

char payload[] = {

0x72, 0x44, 0x52, 0x49, // Header

0x01, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // DeviceId

0xf8, 0x01, 0x00, 0x00, // FileId

0x08, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // CompletionId

0x0e, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // MajorFunction (Device Control Request)

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // MinorFunction

0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, // OutputBufferLength

0xff, 0x10, 0x00, 0x00, // InputBufferLength

0xa8, 0x00, 0x09, 0x00, // IoControlCode

0x00, 0x11, 0x00, 0x00, // Padding

0x20, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // Padding

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // Padding

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // Padding

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00 // Padding

};

It is a Device I/O Request PDU (0x4952) of sub-type Device Control Request (0x000e). More specifically, the I/O Request handler, DrDevice::ProcessIORequest, dispatches the PDU to a Smart Card sub-protocol handler (W32SCard::MsgIrpDeviceControl). Eventually, the value of the field OutputBufferLength (DWORD) is used for a malloc call on the client (inside DrUTL_AllocIOCompletePacket).

This bug is less powerful than the CLIPRDR one because it only goes up to a 4 GB allocation. Also, it only works once (the payload won’t work twice in the same RDP session), so the value of OutputBufferField should be premedidated — we can’t do small increments.

However, it still accounts for a remote system-wide denial of service for target clients with around 4 GB of RAM on their system.

Remote Heap Leak / ASLR Leak in RDPDR

This vulnerability resides in RDPDR’s Printer sub-protocol. It was assigned CVE-2021-38665.

I covered it in depth in a dedicated article: Remote ASLR Leak in Microsoft’s RDP Client through Printer Cache Registry.

If you haven’t already, check it out now (or after having finished reading this article)!

Deserialization Bug / Heap Corruption in RDPDR

This vulnerability resides in RDPDR’s Smart Card sub-protocol. It was assigned CVE-2021-38666.

Likewise, I covered it in depth in a dedicated article: Remote Deserialization Bug in Microsoft’s RDP Client through Smart Card Extension.

Conclusion

I would like to thank Thalium for giving me the opportunity to work on this subject which I had a lot of fun with, and that also allowed me to skill up in Windows reverse engineering and fuzzing.

Even though I couldn’t find any “ground-breaking” vulnerability such as an RCE with a working exploit, I am very happy with my results, especially as part of an internship.

To recap, my findings led to:

- CVE-2021-38665 (Remote ASLR Leak in Microsoft’s RDP Client through RDPDR)

- CVE-2021-38666 (Remote Deserialization Bug in Microsoft’s RDP Client through RDPDR)

I also got two CVEs in FreeRDP. I didn’t talk about these because they’re not about the Microsoft client, they’re not the most interesting and the article is getting really long either way, but feel free to look them up:

- CVE-2021-37594 (Remote Memory Leak in FreeRDP through CLIPRDR)

- CVE-2021-37595 (Remote Arbitrary File Read in FreeRDP through CLIPRDR)

Timeline

- 2021-07-22 — Sent vulnerability reports to Microsoft Security Response Center.

- 2021-07-22 — Sent vulnerability reports to FreeRDP; they pushed a fix on the same day.

- 2021-07-23 — Microsoft started reviewing and reproducing.

- 2021-07-27 — MITRE assigned

CVE-2021-37594andCVE-2021-37595to my FreeRDP findings. - 2021-07-28 — FreeRDP released version 2.4.0 of the client and published security advisories.

- 2021-07-30 — Microsoft assessed the CLIPRDR malloc DoS bug as low-severity and closed the case.

- 2021-07-31 — Microsoft acknowledged the RDPDR deserialization bug and started developing a fix. They also started reviewing this case for a potential bounty award.

- 2021-08-03 — Microsoft acknowledged the RDPDR heap leak bug and started developing a fix. They also started reviewing this case for a potential bounty award.

- 2021-08-04 — Microsoft assessed the RDPDR deserialization bug as Remote Code Execution with Important severity. Bounty award: $5,000.

- 2021-08-04 — Microsoft assessed the RDPDR heap leak bug as Information Disclosure with Important severity. Bounty award: $1,000.

- 2021-08-13 — The vulnerabilities were assigned CVE-2021-38665 and CVE-2021-38666.

- 2021-08-26 — Microsoft assessed the RDPDR malloc DoS bug as low-severity and closed the case.

- 2021-11-09 — Microsoft released the security patch. For some reason, the severity of CVE-2021-38666 was revised to Critical when it was published.