Remote Deserialization Bug in Microsoft's RDP Client through Smart Card Extension (CVE-2021-38666)

This is the third installment in my three-part series of articles on fuzzing Microsoft’s RDP client, where I explain a bug I found by fuzzing the smart card extension.

Other articles in this series:

- Fuzzing Microsoft’s RDP Client using Virtual Channels: Overview & Methodology

- Remote ASLR Leak in Microsoft’s RDP Client through Printer Cache Registry (CVE-2021-38665)

- Remote Deserialization Bug in Microsoft’s RDP Client through Smart Card Extension (CVE-2021-38666)

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Fuzzing RDPDR, the File System Virtual Channel Extension

- Analyzing crashes

- Heap corruption

- Exploitation

- Reporting to Microsoft

- Disclosure Timeline

Introduction

The Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) is a proprietary protocol designed by Microsoft which allows the user of an RDP client software to connect to a remote computer over the network with a graphical interface. Its use around the world is very widespread; some people, for instance, use it often for remote work and administration.

Most of vulnerability research is concentrated on the RDP server. However, some critical vulnerabilities have also been found in the past in the RDP client, which would allow a compromised server to attack a client that connects to it.

At Blackhat Europe 2019, a team of researchers showed they found an RCE in the RDP client. Their motivation was that North Korean hackers would alledgely carry out attacks through RDP servers acting as proxies, and that you could hack them back by setting up a malicious RDP server to which they would connect.

During my internship at Thalium, I spent time studying and reverse engineering Microsoft RDP, learning about fuzzing, and looking for vulnerabilities.

In this article, I will explain how I found a deserialization bug in the Microsoft RDP client, but for which I unfortunately couldn’t provide an actual proof of concept.

If you are interested in details about the Remote Desktop Protocol, reversing the Microsoft RDP client or fuzzing methodology, I invite you to read my first article which tackles these subjects.

Either way, I will briefly provide some context required to understand this article:

- The target is Microsoft’s official RDP client on Windows 10.

- Executable is

mstsc.exe(in system32), but the main DLL for most of the client logic ismstscax.dll. - RDP uses the abstraction of virtual channels, a layer for transporting data.

- For instance, the channel

RDPSNDis used for audio redirection, and the channelCLIPRDRis used for clipboard synchronization.

- For instance, the channel

- Each channel behaves according to separate logic and its own protocol, which official specification can often be found in Microsoft docs.

- Virtual channels are a great attack surface and a good entrypoint for fuzzing.

- I fuzzed virtual channels with a modified version of WinAFL and a network-level harness.

Fuzzing RDPDR, the File System Virtual Channel Extension

RDPDR is the name of the static virtual channel which purpose is to redirect access from the server to the client file system. It is also the base channel that hosts several sub-extensions such as the smart card extension, the printing extension or the serial/parallel ports extension.

RDPDR is one of the few channels that are opened by default in the RDP client, alongside other static channels RDPSND, CLIPRDR, DRDYNVC. This makes it an even more interesting target risk-wise.

Microsoft has some nice documentation on this channel. It contains the different PDU types, their structures, and even dozens of examples of PDUs which is great for seeding our fuzzer.

Fuzzing RDPDR yielded a few small bugs, as well as another bug for which I got a CVE (see my previous article: Remote ASLR Leak in Microsoft’s RDP Client through Printer Cache Registry).

The bug detailed in this article is one of the denser bugs I’ve had to deal with among my RDP findings. It was found by analyzing crashes that I got during fuzzing. It may sound obvious, but it’s actually not; for instance, the previous vulnerability I found had no crash associated to it :)

Analyzing crashes

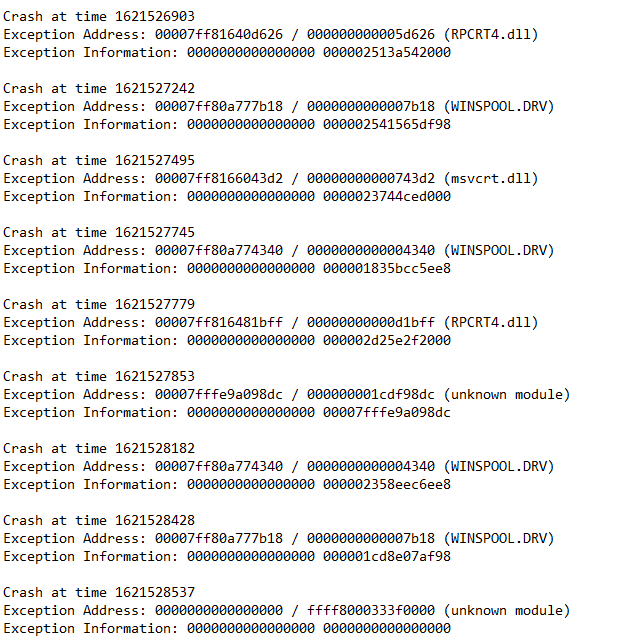

The crashes happened while fuzzing the Smart Card sub-protocol, and were quite… enigmatic.

There were a lot of crashes, in many different modules, and also (not showed on screenshot) in mstscax.dll. In fact, there were way too many crashes at random places for all of this to make any sense, so I thought something was broken with my fuzzing.

Although, one crash seemed to reoccur more frequently inside RPCRT4.DLL. We’ve gotten a tiny glimpse of RPC while investigating DRDYNVC in the first article, but it’s gonna get more serious now.

Smart Cards and RPC

The crashes in RPCRT4.DLL arise in NdrSimpleTypeConvert+0x307:

mov eax, [rdx] ; crash

bswap eax

mov [rdx], eax

It’s a classic out-of-bounds read on what seems to be the byteswap of a DWORD in the heap.

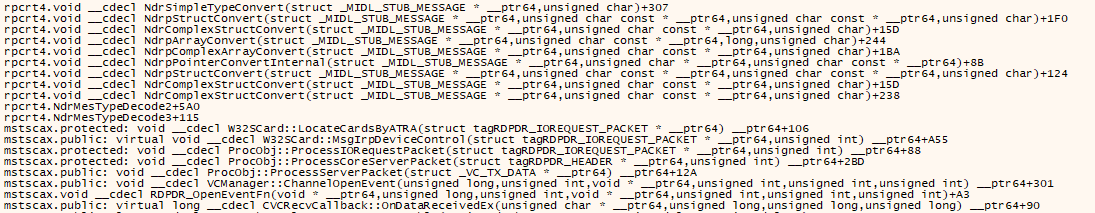

Fortunately, we are able to find the associated payload and instantly reproduce the bug. Here’s what the call stack looks like when the crash occurs:

So before entering RPCRT4.DLL, we were in mstscax!W32SCard::LocateCardsByATRA. But actually, if we also analyze other payloads that lead to the same crash, the call stack will interestingly point out other functions in mstscax.dll, such as:

W32SCard::HandleContextAndTwoStringCallWithLongReturnW32SCard::WriteCacheW32SCard::DecodeContextAndStringCallW- …

What’s with all of these? Here’s one thing all these functions have in common: the following snippet of code.

v6 = MesDecodeBufferHandleCreate(

&PDU->InputBuffer,

PDU->InputBufferLength,

&pHandle

);

// ...

NdrMesTypeDecode3(

pHandle,

&pPicklingInfo,

&pProxyInfo,

(const unsigned int **)&ArrTypeOffset,

0xEu,

&pObject

); // Crash here

The only thing that varies across these functions is the fifth parameter of NdrMesTypeDecode3 (the 0xE). We also immediately notice that PDU->InputBufferLength (DWORD) can be arbitrarily large…

Before going any further, let’s dissect two of the guilty payloads as well.

rpc-crash-1

72 44 52 49 01 00 00 00 f8 01 02 00 08 00 00 00 0e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 DeviceIoRequest

00 40 00 00 OutputBufferLength

00 80 2d 00 InputBufferLength

e8 00 09 00 IoControlCode

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 02 00 08 00 Padding

InputBuffer

01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 03 00 08 00 01 40 00

00 16 00 00 00 01 00 00 00

rpc-crash-2

72 44 52 49 01 00 00 00 f8 00 00 00 04 10 00 00 0e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 DeviceIoRequest

00 40 00 00 OutputBufferLength

6f 63 06 00 InputBufferLength

64 00 09 00 IoControlCode

00 00 ff 00 00 00 00 40 00 20 00 66 00 00 77 66 64 63 08 00 Padding

InputBuffer

01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 0e

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 6f 63 06 00 64

00 09 00 00 00 ff 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 6c 00 00 05

So those are Device I/O Request PDUs, more specifically of sub-type Device Control Request. We already met one in the first article, in the arbitrary malloc bug.

But what is this IoControlCode field exactly? According to the specification:

IoControlCode (4 bytes): A 32-bit unsigned integer. This field is specific to the redirected device.

Specific to the redirected device… For some reason, it took me a long time to realize there was actually a dedicated specification for the Smart Card sub-protocol (as well as the others).

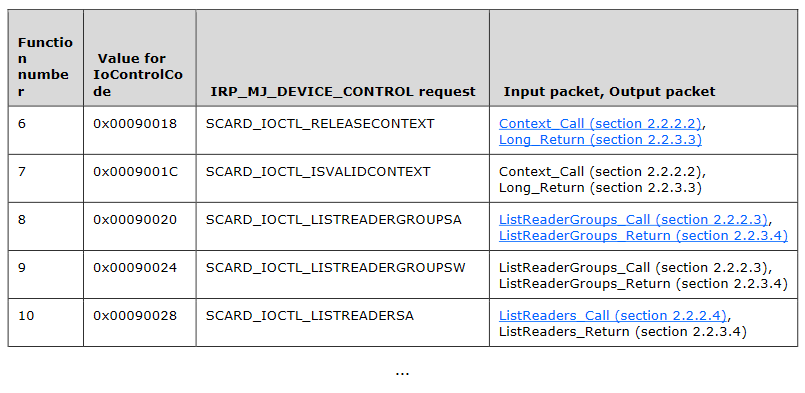

The section 3.1.4 of the Smart Card specification answers our suspicion. It contains a long table that maps IoControlCode values with types of IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL requests and associated structures.

Therefore, there are around 60 functions that contain the same pattern of code using MesDecodeBufferHandleCreate followed by NdrMesTypeDecode3. They are all called the same way with our InputBuffer and InputBufferLength — only a certain offset parameter varies each time.

According to the specification, for IoControlCode set to 0x000900E8, we get the following LocateCardsByATRA_Call structure:

typedef struct _LocateCardsByATRA_Call {

REDIR_SCARDCONTEXT Context;

[range(0,1000)] unsigned long cAtrs;

[size_is(cAtrs)] LocateCards_ATRMask* rgAtrMasks;

[range(0,10)] unsigned long cReaders;

[size_is(cReaders)] ReaderStateA* rgReaderStates;

} LocateCardsByATRA_Call;

It seems then that based on IoControlCode, our input buffer will be decoded according to a certain structure.

The RPC NDR marshaling engine

Let’s come back on the decoding piece of code:

v6 = MesDecodeBufferHandleCreate(

&PDU->InputBuffer,

PDU->InputBufferLength,

&pHandle

);

This function from RPCRT4 is documented by Microsoft:

The MesDecodeBufferHandleCreate function creates a decoding handle and initializes it for a (fixed) buffer style of serialization.

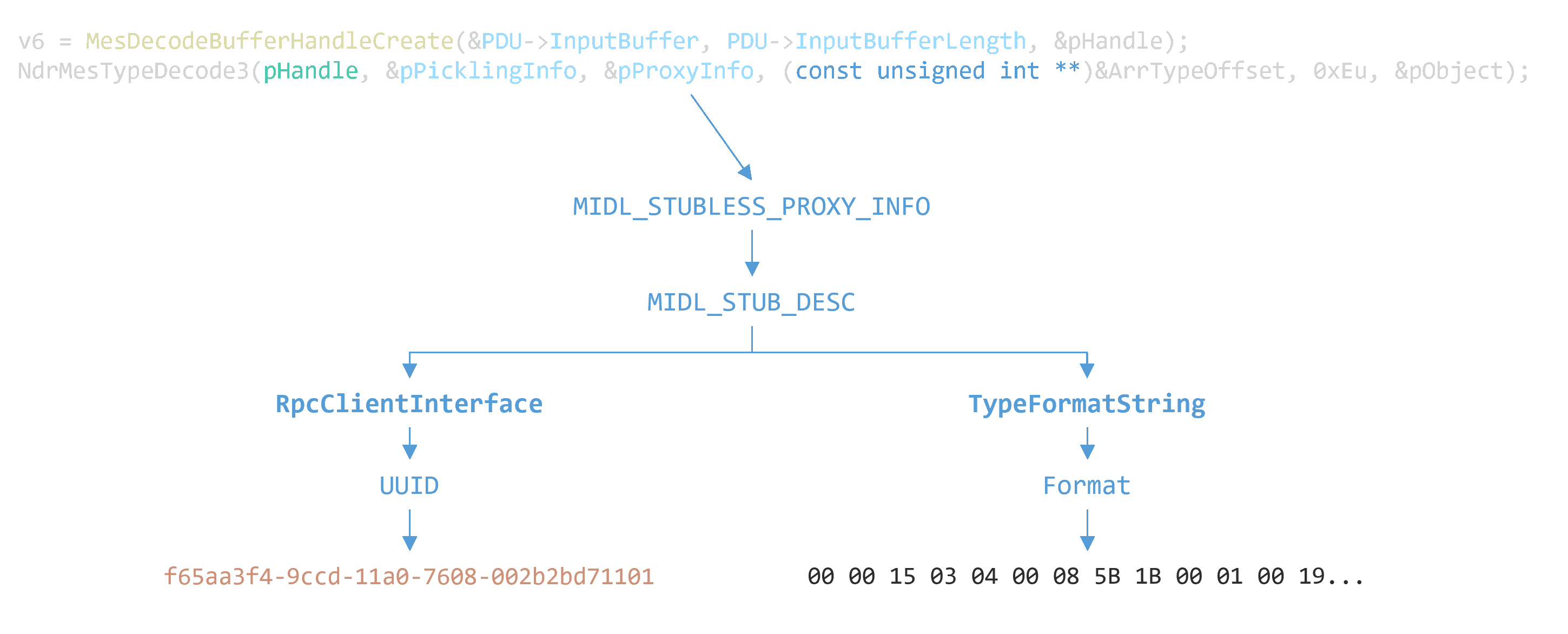

So this is what it is all about… RPC has its own serialization engine, called the NDR marshaling engine (Network Data Representation). In particular, there is documentation on how data serialization works: header, format strings, types, etc.

The RDP client makes “manual” use of the RPC NDR serialization engine to decode structures from the PDUs.

After having initialized the decoding handle with the input buffer and length, the data is effectively deserialized:

NdrMesTypeDecode3(

pHandle,

&pPicklingInfo,

&pProxyInfo,

(const unsigned int **)&ArrTypeOffset,

0xEu,

&pObject

);

And to our surprise… the function NdrMesTypeDecode3 is nowhere to be documented! The reason is because developers are not supposed to use this function directly.

Instead, one should describe structures using Microsoft’s IDL (Interface Description Language). Next, the MIDL compiler should be used to generate stubs that can encode and decode data (using the NdrMes functions underneath).

Nonetheless, header files contain information about the parameters and their types that can help us understand a bit more.

In particular, the pProxyInfo argument eventually leads to a Format field. It seems to contain a compiled description of all the types that exist and are used within the Smart Card extension.

Then, the ArrTypeOffset array, which starts like this: 0x02, 0x1e, 0x1e, 0x54, ..., lists the offsets of all the structures of interest inside the compiled format string. The next argument (0xE) is the offset, in the ArrTypeOffset array, of the structure we want to consider.

For LocateCardsByATRA, 0xE gives an offset of 0x220 in the ArrTypeOffset array, which points to the compiled format associated to the structure we found earlier in the specification:

typedef struct _LocateCardsByATRA_Call {

REDIR_SCARDCONTEXT Context;

[range(0,1000)] unsigned long cAtrs;

[size_is(cAtrs)] LocateCards_ATRMask* rgAtrMasks;

[range(0,10)] unsigned long cReaders;

[size_is(cReaders)] ReaderStateA* rgReaderStates;

} LocateCardsByATRA_Call;

We are lucky the specification tells us everything about the type structures, and even releases the full IDL in appendix. If we didn’t have these, we would have had to decompile the format ourselves, and not only the format pointed by the offset we found. Indeed, there are also many references to other previously defined structures, such as LocateCards_ATRMask.

Root cause

This may be getting a bit hard to follow, so let’s summarize what we understand for now:

- We can send an

IoControlCode,InputBufferandInputBufferLength. - The

InputBufferLength(DWORD) can be greater than the actual length ofInputBuffer. - The input buffer will be deserialized (through the RPC NDR marshaling engine) according to a structure that varies with

IoControlCode. - There are around 60 possible

IoControlCodevalues, and thus decoding structures. - There’s an OOB read during the deserialization process, in a certain function

NdrSimpleTypeConvert.

Now as I was reversing and debugging, it seemed to me that these “convert” operations actually took place before any real decoding per se. It was as if before deserializing, there was a first pass on the whole buffer to convert stuff.

I eventually found a Windows XP source leak that helped shed light on all of this:

void NdrSimpleTypeConvert(PMIDL_STUB_MESSAGE pStubMsg, uchar FormatChar) {

switch (FormatChar) {

// ...

case FC_ULONG:

ALIGN(pStubMsg->Buffer,3);

CHECK_EOB_RAISE_BSD( pStubMsg->Buffer + 4 );

if ((pStubMsg->RpcMsg->DataRepresentation & NDR_INT_REP_MASK) != NDR_LOCAL_ENDIAN) {

*((ulong *)pStubMsg->Buffer) = RtlUlongByteSwap(*(ulong *)pStubMsg->Buffer);

}

pStubMsg->Buffer += 4;

break;

// ...

}

}

The magic happens when the endianness of the serialized data does not match with the local endianness. A pass on the buffer is performed to switch the endianness of (in particular) all the FC_ULONG type fields (the unsigned long fields in our structure).

Therefore, in the _LocateCardsByATRA_Call structure, the fields cAtrs and cReaders are byteswapped. But also and more importantly, any unsigned long that lies inside the nested rgAtrMasks or rgReaderStates fields will be byteswapped. And these fields are arrays of structs which size we control!

So there are actually two kinds of overruns here:

- the user-supplied

PDU->InputBufferLengthis not properly checked, so the conversion pass in the RPC NDR deserialization will go way beyond the end of the PDU in the heap; - the user-supplied

cAtrs(orcReaders) that is coded inside the serialized data can be large enough to make the deserialization structure overflow the actual length of the buffer, along with the input buffer length we provided.

Combined, these overruns result in an out-of-bounds read in the heap, and thus a crash.

Heap corruption

We managed to clear up why we got crashes in RPCRT4.DLL, and which payloads triggered them. However, we haven’t found yet an explanation to the tons of other nonsensical crashes we’ve had.

Let’s check the LocateCards_ATRMask structure, that is nested inside LocateCardsByATRA_Call:

typedef struct _LocateCards_ATRMask {

[range(0, 36)] unsigned long cbAtr;

byte rgbAtr[36];

byte rgbMask[36];

} LocateCards_ATRMask;

There’s an unsigned long field (cbAtr) at the beginning of this struct of total size 76 bytes. Therefore, we may be able to perform byteswaps of DWORDs in the heap every 76 bytes!

We can confirm this by setting a breakpoint where the byteswap occurs and watching the heap progressively getting disfigured.

Since the PDU->InputBufferLength variable is arbitrarily large, we can, as we said, eventually reach the end of the heap segment to cause an OOB read crash. But this is not the interesting thing here.

By byteswapping DWORDs in the heap, we are corrupting a lot of objects. If the input buffer length is large enough to allow out-of-bounds operations, but small enough not to exceed the heap segment, the deserialization process will return with a damaged heap. This leads to numerous types of crashes; all the odd unexplained crashes that I encountered earlier.

- Heap Corruption exceptions during heap management calls

- Random pointers being damaged and causing access violations

- Damaged vtable pointers causing access violations

- Damaged vtable pointers that still successfully resolve and redirect the execution flow, of course directly crashing after (illegal instruction)

- The “unknown module” crashes I found earlier!

Exploitation

I suspect some of these behaviors could be exploited to achieve unexpected harmful results such as remote code execution.

For instance, I thought that with some heap spray, one could manage to hijack a vtable through a well-aligned byteswap and redirect the execution flow. But it seemed quite tricky to carry out and I did not manage to exploit it myself.

There may also be other repercussions of this deserialization bug. I saw that there were other kinds of conversions that could be performed: float conversions, EBCDIC <-> ASCII… but I’m not sure whether it is actually possible to trigger them.

Reporting to Microsoft

At first, I was hesitant about whether I should report this to MSRC or not. Indeed, I was very unsure about this bug’s exploitability, which seemed to me like it would be very intricate and relying on a lot of luck.

Moreover, by submitting it, I would have to tag it as Remote Code Execution, which I thought would be a bold move without any proof of concept.

I still reported it to MSRC, and rightfully so, as it was assessed Remote Code Execution with Critical severity and awarded a $5,000 bounty!

In conclusion, don’t be afraid to submit bugs even if you lack proof of exploitation. As long as you have a very detailed explanation of the bug, a good understanding of the root cause and a decent analysis of the risks that come with it, it can be acknowledged and awarded.

The exploitation process can sometimes require a lot of skill and creativity, and you can always tell yourself that even if you can’t exploit your own bug, there may be an evil super hacker out there that would manage to exploit it — better be safe than sorry.

Disclosure Timeline

- 2021-07-22 — Sent vulnerability report to MSRC (Microsoft Security Response Center)

- 2021-07-23 — Microsoft started reviewing and reproducing

- 2021-07-31 — Microsoft acknowledged the vulnerability and started developing a fix. They also started reviewing this case for a potential bounty award.

- 2021-08-04 — Microsoft assessed the vulnerability as Remote Code Execution with Important severity. Bounty award: $5,000.

- 2021-08-13 — The vulnerability was assigned CVE-2021-38666.

- 2021-11-09 — Microsoft released the security patch. For some reason, the severity was revised to Critical when the CVE was published.